MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

38 medieval questions you are afraid to ask – all answered below in our Beginner’s Guide to the Middle Ages.

This is a beginner’s guide.

If you’re an expert, use our Medieval Guidebook to go one step further.

Everybody has at least one medieval image inside their head. Towering castles. Gallant knights. Damsels in distress. Sieges and crusades. Crossbowmen and gunpowder. Khans and caliphs. Monks, monasteries, and manuscripts.

But how to make sense of it all? Below follows a humble attempt.

The Middle Ages were the period in history between Antiquity (think: Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, etc) and the Renaissance (think: Leonardo da Vinci, Columbus, Copernicus, etc).

The above doesn’t even begin to cover the millennium of history that is the Middle Ages. Keep scrolling to find more answers.

Tip: Explore our Medieval Guidebook to dive deeper into a host of subjects.

Important aspects of medieval life are the central role of the community and a strict class society.

The community was at the center of medieval thinking. Whether we take a look at Western feudalism, the Islamic ummah, or the role of the state as an enlarged family in Confucian thought, we find little place for individual wants and needs. In medieval life, you took care of the community so that it took care of you, too.

These communities were strictly organized into hierarchies, with a king, emperor, pope, caliph or khan at the top. Wars were actually fought over the question who reigned supreme. The rest of the pyramid was structured into many layers of dukes, counts, emirs, sultans, bishops, magistrates, samurai, and so on – all the way down to the poorest serf.

All stations were expected to play their part, thus both master and slave of their role in society.

The Middle Ages are among the most important periods of history. Many modern nations backtrack their origins to this era. And many of our traditions and tales stem from medieval roots.

Let’s take a look at a few examples. The Middle Ages…

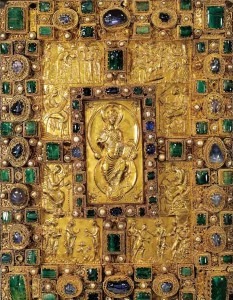

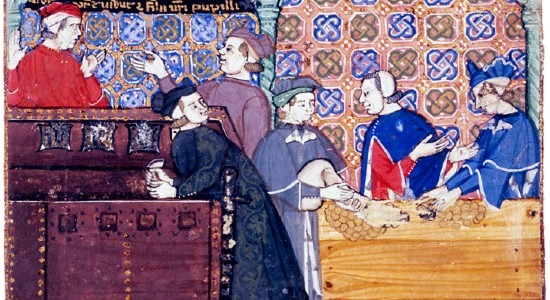

Medieval art is vast, splendid, and beautiful. Religious motifs were very common. Most art depicted saints, pagan deities, and buddhas. Mosaics, statues, stained glass, tapestry, and wood and ivory carving usually ran along this theme. Additionally, the architecture containing them – cathedrals, mosques, stupas, pagodas, wats, and so forth – were usually great pieces of art in and of themselves.

In the east, more “secular” art was also made. Because most muslims believe depicting Allah is idolatry, Islamic art contains great examples of geometric patterns. Even further east, especially in China, vases were also very popular. They usually carried natural motifs, like trees, mountains, and rivers. And in all medieval cultures, calligraphy was a way of writing but an art form in and of itself, too.

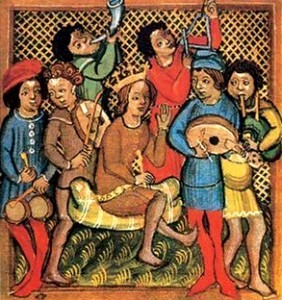

The Middle Ages were very musical. Most medieval music was sacred, but there was also non-religious music. Overall, the music was very vocal (think: Gregorian chant or choral music).

Traveling artists called troubadours composed and spread non-religious music. They traveled from court to court to entertain noble lords and ladies with tales about chivalry and courtly love. They were the fantasy writers of their age – Dante himself called their genre “rhetorical, musical, and poetical fiction”.

Yes. The word medieval comes from the Latin medium aevum, which means “middle age”. The term became common during the 19th century. That’s when most historians started to distinguish between the historical eras of Antiquity, the Middle Ages (or Medieval Times / Era), and the Modern Age.

The ending -al is actually quite common in the English language (think: classical, historical, etc).

If you’re wondering why the Middle Ages are called “middle”, we got you covered.

No. And hell, no!

Let’s explain the first “no”. The Dark Ages were used to refer to the Early Middle Ages. The term was minted by scholars during the Renaissance, a period following the Middle Ages. They were so in love with Antiquity that they assumed civilization must have died after the Fall of Rome. So they introduced the concept of a “dark age”.

Then, the “hell no”. The term “Dark Ages” is no longer in use by self-respecting historians. It was a frame used by Renaissance thinkers to pedestalize the culture they were trying to imitate: Classical Antiquity. In our day and age, scholars refer to the period as the Early Middle Ages. The period was anything but “dark” and, fortunately, starts to see the light of day in historical research. One of the reasons Medieval Reporter was founded, was to shed light on this fascinating period.

Tip: Read our articles on the Early Middle Ages to illuminate your understanding of this era.

No. The Renaissance is commonly understood as the period following the Middle Ages. The term itself does pose a problem, though. Its meaning, “rebirth”, implies medieval civilization was “dead” or nonexistent.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The Renaissance would not have been possible without the Middle Ages occurring first. In many ways, the Renaissance built upon medieval foundations.

Some important differences between the Medieval and Renaissance Eras are:

The Early and Late Middle Ages are the beginning and the ending of the Medieval Era, respectively. The Early Middle Ages were previously known as the Dark Ages. The Late Middle Ages are seen as the death of a great era or the run-up towards the Renaissance Era – depending on who you ask.

The High Middle Ages are the center of the Medieval Era. It’s the period between the Early and Late Middle Ages. It’s called “High” because medieval civilization was at its peak.

If you’re wondering when these eras started and ended, we’ve got you covered.

Tip: See also our answer to the question ‘When did the Early / High / Late Middle Ages take place?’

Although this is framed as a what question, this is better answered under when.

Nobody woke up one day and found out that the Middle Ages had ended. That’s not how great eras come to an end. But it’s fair to say that in most places, somewhere in the 15th century, a transition period started. A transition to a new age.

The Middle Ages ended for a number of reasons, for example:

Tip: See also our answer to the question ‘How did the Middle Ages end?’

Yes and no. This is more of a linguistic question, but obviously important for anybody wanting to write about the Middle Ages. The answer is: “Middle Ages” is capitalized, “medieval” is not.

This is because the Middle Ages is a noun, just like “Antiquity” or the “Great Depression”, whereas medieval is an adjective, like “ancient” or “modern”. So you would write about medieval civilization, just like you would spell classical music or baroque architecture.

It sometimes gets a little confusing, though. That’s because a common way of using the word “medieval” is in combination with “era”. This leads to Medieval Era, which is capitalized because it starts to behave like a noun – just like Classical Antiquity.

You can blame English for this, one of the most peculiar of the Western (or western?) languages.

These were our most frequently asked what questions.

Check the table of contents to find when and other questions.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Now this is where things start to get truly interesting! When the Middle Ages took place is a matter of great debate. Great eras do not start and end on a single date, leaving room for interesting discussions.

Historians call this periodization.

The Middle Ages started when Late Antiquity came to an end. In most places, a transition period from imperial authority to a feudal society was already well underway by then. The starting date for the Medieval Era varies per region.

It’s impossible to pick a single starting date for the Middle Ages. In everyday conversation in the Western world, it’s common to use the average date of 500 CE. But in other parts of the world, this date may come across as eurocentric or even colonial – as does the entire concept of “the Middle Ages“.

Just like with the starting date, there is no universally agreed-upon end date for the Middle Ages. That’s because the definition of the “end of the Medieval Era” varies from region to region.

In Europe, it’s commonly said that the dawn of the Renaissance Era marks the end of the Middle Ages. But in Central Eurasia, one usually uses the rise of the Gunpowder Empires as the close of the Medieval Era. And in the Americas, there’s no Renaissance at all, but a Spanish-induced genocide that hallmarks the “Age of Discovery” for the native population.

It’s quite difficult to pinpoint the exact year when the Middle Ages ended. In everyday talk in the Western world, it’s common to use the average date of 1500 CE. The examples listed below demonstrate that this is – again – rather eurocentric, so be aware that different cultures look back in time in very different ways.

Disclaimer: the concept of the Middle Ages, in general, is a rather Western idea, even though parts of it can be applied elsewhere. The division into Early, High and Late Middle Ages is even more eurocentric. That’s why an answer to this question only makes sense if we focus it on Europe.

Sorry, Asia, Arabs and Aztecs.

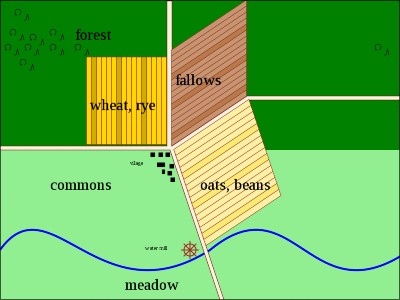

The Early Middle Ages lasted from roughly the late 5th to the late 10th / early 11th century CE. The period started with great migrations (Saxons in Britannia, Visigoths in Hispania, Vandals in Africa, and so on). People left the cities and increasingly worked the land, as society became more agricultural and less mercantile. By the end of the period, innovations in crop rotation allowed for population expansion. An imperial crown was reintroduced in Western Europe, but Scandinavian raiders (Vikings) plundered most European coastlines. In the east, the Byzantine Empire survived the Migration Period and the great Tang dynasty ruled China. But it was the Islamic Caliphate centered around Baghdad that was truly the center of the world.

Tip: Explore this era further. Read our reports on the Early Middle Ages.

The High Middle Ages lasted from roughly the early 11th to the late 13th / early 14th century CE. The population continued to grow and urban city centers became more powerful in places like Italy, where the first university was founded. Europe stabilized, as hitherto fringe countries such as Norway, Sweden and Hungary were integrated into the christian core of Western Europe. A population surplus led to violent expeditionary explosions, such as the Crusades. One of these expeditions targeted the struggling Byzantine Empire, which never fully recovered from the blow. By the end of the period, both Europe and the Arab world were on the receiving end of Mongol invasions – which terminated the Islamic Caliphate.

Tip: Explore this era further. Read our reports on the High Middle Ages.

The Late Middle Ages, then, lasted from roughly the early 14th to the late 15th / early 16th century CE. Europe was plagued by disasters, such as the Great Famine and the Black Death. Between the English and the French kings, a war that lasted over a century ravaged and depleted both countries in terms of resources and manpower. Corruption and conflict decreased the reputation of the Catholic Church throughout Europe. The Byzantine Empire came under attack from the Ottoman Turks, who eventually captured Constantinople. But from Iberian ports, ships left for increasingly exotic destinations, discovering new routes to both the Caribbean and India – thereby contributing to the end of the Medieval Era.

Tip: Explore this era further. Read our reports on the Late Middle Ages.

Oh no, we’re not doing this again!

These were our most frequently asked when questions.

Check the table of contents to find how and other questions.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

In addition to what happened and when it happened, it’s interesting to take a look at how things took place. That’s why we’ll answer questions here regarding the start of the Early Middle Ages and the end of the Late Middle Ages.

In Europe, the Middle Ages started with the fall of the Roman Empire. In Late Antiquity, there was a shortage of labor. Large Roman landowners tied tenants legally to their land to prevent them from moving away.

Simultaneously, political unrest in the Late Empire threatened long trade routes. The economy became more local and self-sufficient. Farmers and craftsmen started to produce for the immediate vicinity instead of the empire.

With trade declining, so did the urban population. At the same time, many Germanic tribes started moving into the Roman Empire – the Migration Period. The Roman emperors themselves frequently invited them in order to fill the depleted ranks of the imperial legions.

Ultimately, the localizing – instead of globalizing – economy fitted neatly with the smaller-scale, Germanic view on society. Most people lived in the countryside as farmers. Towns and small cities were ruled by governors, who grouped together on the battlefield when called upon by their king.

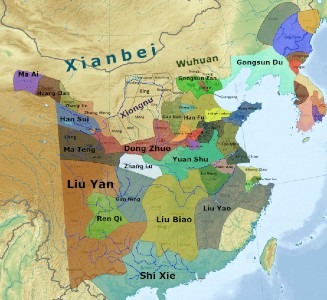

This was how Western Europe came to be organized at the start of the Middle Ages. In other regions, the Middle Ages began with the teachings of Muhammad in Arab culture and the end of the Han dynasty in Chinese culture – ushering in the medieval Three Kingdoms period.

In Western Europe, mainly by localization. With the fall of the Roman Empire, the imperial economy fragmented as well. No longer did metal from the British Isles find its way to Egypt or were furs from Germanic lands transported to the Iberian Peninsula.

Most craftsmen in Western Europe started creating products for their own region or perhaps the rest of the kingdom. “International” trade declined sharply, evidenced by a very small number of shipwrecks from this period. A lot of people became farmers and relied on barter.

As a result, money largely disappeared from the medieval economy. People were paid in goods and services. And the most important service was fealty (literally: faithfulness).

This meant that the serf owed fealty (loyalty and military service) to the lord, who had – in turn – to protect his serfs. The lord owed fealty to the king, who had to protect his lords and rewarded their service with goods, mostly land. This system is called feudalism.

The feudal system was in use in Europe, India and Japan in one form or another. In the Arab world, the Middle Ages obviously differ from Antiquity by the islamization of society. In the Byzantine Empire, the differences are not so stark: they viewed themselves as Romans until the Fall of Constantinople in the Late Middle Ages.

In many ways, the (Early) Middle Ages are a continuation of Late Antiquity. The localization or deglobalization of the Roman economy was well underway before the Migration Period started. “Barbarians” were settled in Roman border provinces to provide manpower, but this jeopardized their loyalty to the far-away imperial center, Rome.

The christianization of Europe progressed throughout the Middle Ages. But before the Medieval Era began, Christianity had spread far and wide in both the Western and Eastern Roman Empire. Antiquity in Europe ended on a christian note as much as the Middle Ages did.

In architecture, Roman forms and techniques were continued throughout the Early Middle Ages, literally called the Pre-Romanesque style. On the battlefield, the Germanic kingdoms of the Early Medieval Era mostly used heavy infantry – just like the Romans and Greeks had done. It was not until they met the medieval Arabs and their cavalry armies that they changed military doctrines – ultimately leading to the popularization of that most medieval of soldiers, the knight.

The Middle Ages ended because of economic changes that posed a threat to the feudal system. During the High Middle Ages, trade started to pick up. The Crusades exposed the nobility to the wealth of the East.

Italian merchants bought these products along the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean coastlines and started selling them in Europe, where demand soared. A lot of money was thus reintroduced into the medieval European economy. And where money played a role, land started to lose its value.

Land, however, was the basis of the feudal system. With land, kings rewarded their lords for extraordinary service. Land brought prestige, power, and the men to field an army with.

With money, kings could simply buy mercenaries and had to rely less on their lords for manpower. Money also allowed royalty to hire civil servants, like sheriffs and bailiffs, that were loyal to the crown. And most importantly, with money kings could buy cannon.

Cannon and other gunpowder weapons transformed the battlefields of the Late Middle Ages. Now any trained man with a musket could kill a knight. The nobility started to lose its military prestige.

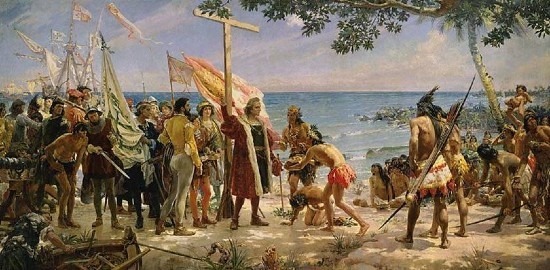

Other important events that heralded the dawn of a new age were the discovery of the Americas, a shattering of the Church over theological disputes, and epidemics and famines that killed so many people that labor conditions and wages of the common folk improved.

Tip: See also our answer to the question ‘Why did the Middle Ages end?’

Probably the most important difference between the two time periods is the philosophy of humanism. In the Middle Ages, the community was all that mattered. And the community ultimately was governed by God, or Allah, or Tengri, or Huitzilopochtli, and so forth.

The Renaissance Era was a very religious era as well. You only have to take a look at the amount of religious conflict in Renaissance Europe to reach that conclusion. However, people started placing mankind in the center of the universe – albeit mostly in art.

Renaissance painting and sculpture are particularly loved for their depiction of human beauty. Additionally, in Renaissancist political philosophy, a country was supposed to be better off with a leader displaying the most amount of virtù. And the most Renaissance ideal of them all was being a uomo universale – very different from the medieval idea of “one community under God”.

The Renaissance sowed the seeds of individualism – a very un-medieval concept.

The term “Renaissance”, by the way, is as problematic as the concept of the Middle Ages. Historians have started referring to the period as the start of the Early Modern Era.

Late Medieval art showed a gradual evolvement towards Renaissance forms. Medieval music laid the foundation for music notation and musical theory, without which baroque and classical music would not have been possible. And a gunpowder-based military, typical of the Renaissance Era, followed from Late Medieval campaigning – the first cannon were used in Europe in the 14th century.

In religious matters, the Late Middle Ages witnessed a lot of criticism directed towards the Church. Most people, devout as they were, wished to repair its errors. This led to a wave of restoration movements.

Only when those seemed to have failed as well, did the Protestant Reformation explode onto the scene.

Regarding the Age of Discovery, Columbus did not magically get the idea to sail to the Americas. He was actually trying to find a route to the Far East. By the end of the Late Middle Ages, Portuguese and Spanish captains had explored the West African shoreline – looking for precisely that – for over a century.

Whether it was by sailing west (which Columbus did) or by rounding Africa (which someone else did), a maritime route to India and China was practically bound to be discovered around the close of the Middle Ages.

Seriously, we’re not doing this.

But we get it if you’re interested in the question why the Dark Ages are called “dark”.

This question may seem a bit odd at first. After all, didn’t colonies come into being in the “Modern” Era? But on closer inspection, the question becomes more interesting.

Postcolonial theory looks at power, religion, culture, and so forth, in terms of colonial hegemony. It specifically tries to bring subjugated voices to light to color a more complete historical narrative. In medieval terms, you can think of examples like pagans, jews, or women in general.

When you research the Middle Ages with 21st-century views like postcolonialism, there’s much to be investigated further. One can think of antisemitism in medieval Spain or a gender history of the Medieval Era. Other examples are the, at times genocidal, exploits of the Teutonic Order or Mongol behavior towards fallen foes.

Whether medieval history is altogether postcolonial is a matter up for debate. But it’s definitely eurocentric to this day. That’s because the entire concept of a Medieval Era is – a matter we touched on earlier.

These were our most frequently asked how questions.

Check the table of contents to find why and other questions.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Having touched upon the what, the when, and the how, it’s time to move on to the most important question of all: why? Why did the Middle Ages take place at all? How did a millennium of history end up being classified as “middle”? And if people went about their medieval business for a thousand years, why did the period even end?

With humans being fans of the Rule of Three, it was a matter of time before history was divided into three parts. In the 14th century, Italian scholar Petrarca came up with the most persistent historical scheme in Western historiography: ancient-medieval-modern.

Petrarca and subsequent “Renaissance” thinkers thought they witnessed the dawn of a new age, the Modern Era. Since they tried to build their blossoming epoch on the foundations of Classical Antiquity, they needed a name for the period in-between. Hence the “Middle Ages” were born.

As with all periodization discussions, “medieval”, “modern” and “Renaissance” are problematic concepts. But, for lack of something better, they are still in use. Most people view their own era as modern: medieval historians thought they lived in modern times.

Since time immemorial, humanity has been fond of the duality between light and dark. Most religions are built on it. Petrarca was the first to come up with a secular interpretation.

Being an early Renaissancist, he was in love with Classical Antiquity. As such, he viewed the era as an epoch of light, followed by a period of darkness. That’s why he introduced the concept of a “Dark Age“.

Initially, they referred to the Early Middle Ages – the period directly following the end of Antiquity. Later, Enlightenment scholars outdid Renaissance thought in both pomp and arrogance. They viewed the entire Middle Ages as a Dark Age, contrasting that “Age of Faith” with their own “Age of Reason”.

Fortunately, historiography has become more reasonable and neutral as of late. That’s why the term Dark Age(s) is no longer used by modern historians.

Yes, we get this one a lot. A textbook example of a “loaded question”. Despite the fact that it shows ignorance in and of itself, we’ll answer it here regardless.

The Middle Ages were anything but ignorant and dark. Magnificent buildings were erected, like Angkor Wat or the Hagia Sophia. Great empires were founded, some among the largest in history. What’s more, the Italian Renaissance wasn’t all that special: the Middle Ages witnessed not one, not two, but three renaissances.

Regarding ignorance, here’s a simple, non-exhaustive list of medieval inventions: the heavy plow, the wheelbarrow, horseshoes, crop rotation, the spinning wheel, the loom, treadmill cranes, chimneys, windmills, flying buttresses, the counterweight trebuchet, the longbow, gunpowder, cannon, grenades, the arquebus, Greek fire, Arabic numerals, the blast furnace, paper, the printing press, eyeglasses, the hourglass, mechanical clocks, magnets, the compass, the winepress, liquor, rat traps, chess, oil painting, and universities.

Anything but a Dark Age, obviously.

The Middle Ages ended because Renaissance thought introduced early individualism. This paved the way for two impactful trends: the Reformation and proto-capitalism.

The Protestant Reformation challenged the authority of the Catholic Church. Protestants introduced the idea that you could directly communicate with God. You didn’t need medieval institutions like a pope for that.

Any individual could talk to God, according to the Reformation – a “democratization” of salvation.

Proto-capitalism meant an early form of capitalism, that allowed “low-born” citizens to gather wealth with which to compete for influence with the nobles. Who needed land to field an army if any rich person could simply hire mercenaries? Money unlocked the true potential of burghers.

The burgeoning bourgeoisie financed expeditions to new-found parts of the world. The maritime routes to the Americas, India and Indonesia were quite dangerous. So, risk-sharing options were introduced in the form of the first stocks – a typical proto-capitalist invention.

In more centrally governed states, royalty rather than burghers profited from newly set up colonies. This flow of fresh wealth happened to accelerate a trend in motion since the Late Middle Ages. It allowed kings to finance a larger and more modern army.

They were specifically interested in cannon. The new gunpowder weapons allowed them to take castles more easily, eroding the power base of feudal lords even further. Money also allowed kings to hire both mercenaries as well as civil servants – more loyal than the average lord as long as you pay up.

All in all, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period saw a long trend of the nobility decreasing in importance. In the end, it would take a French Revolution and more to get rid of the medieval class society. But many trends that led to the Late Modern Period started in the Late Middle Ages.

Tip: See also our answer to the question ‘What ended the Middle Ages?’

These were our most frequently asked why questions.

Check the table of contents to find who and other questions.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

After learning what went down, how it happened, why events unfolded the way they did, and – not unimportant for (aspiring) historians – when it all took place, you may be interested in who the major players were. After all, every piece in the game gets moved by another piece, right? Below follow the who questions we get asked the most – topped off by a small where bonus.

The Franks were a Germanic people that crossed from lands in present-day Germany and the Netherlands into the Roman Empire. They proceeded to found a state there that would go on the become the largest empire of the Western European Early Middle Ages. Charlemagne is perhaps the most famous Frank of all time.

Tip: Explore our Guidebook page on the Franks to dive deeper into the subject.

The Vikings were Scandinavian raiders that plundered, pirated, and looted a lot of European shorelines and river banks during the Early Middle Ages. By the end of the era, they started trading and settling in some of the areas they had been hitting, most notably Normandy, Ukraine and Sicily. Though mostly of Norse origin, “Viking” is more of a job description or an occupation than a reference to ethnicity.

Tip: Explore our Guidebook page on the Vikings to dive deeper into the subject.

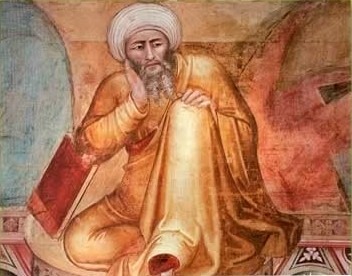

The Middle Ages were a period of great philosophical advancements, mainly focused on joining science with faith. Arab, Persian and Indian scholars commented and improved upon ancient philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato. An Indian called Aryabhata “invented” the mathematically important number 0, revolutionizing arithmetic throughout the Arab, Khmer and Chinese worlds.

Europe caught on a little later but saw great progress during the High Middle Ages in the fields of metaphysics, ethics and logic. A great medieval philosopher was Thomas Aquinas, who tried to reconcile Aristotle’s teachings with christian tenets. Other notable Middle Ages philosophers were Albertus Magnus, Anselm, Augustine, Averroes, Avicenna, Bonaventure, Boethius, Gersonides, Ibn Khaldun, Pseudo-Dionysius, Roger Bacon, and so on.

Everybody did. Great eras come to a close because people start focusing on other things.

Kings started equipping armies with guns and cannon, eclipsing feudal lords. Burghers became wealthier and added to the economical weight of urban centers, eclipsing the countryside in importance. Protestants and other reformists shattered the medieval unity of the Church. Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals established great Gunpowder Empires from the Bay of Bengal to the Balkans. And in China, the mighty Qing dynasty replaced the medieval Ming.

If you want names, there’s a couple of people you can “blame”. Take Columbus for discovering the Americas. Or Cortés and Pizarro for toppling the Aztec and Incan Empires, respectively. Blame Mehmed II for conquering Constantinople and terminating the Byzantine Empire. Condemn Luther for sparking the Reformation. Or hold Nurhaci responsible for pushing China into the Modern Era.

Seriously though, people simply moved on to other priorities – as they always do.

Tip: See also our answer to the question ‘Why did the Middle Ages end?‘

If you understand the Middle Ages as a period of time, a true medium aevum, then the answer is: everywhere – because the question makes as much sense as “Where is March?”

But if you understand the Medieval Era as a cultural, social, political, economic, and military phenomenon, the question becomes more interesting. For a long time, historians assumed the Middle Ages took place in Europe. To imply that other cultures went through a similar ancient-medieval-modern transition was deemed eurocentric.

It has, however, become increasingly clear that a lot of cultures did indeed follow that path, like Japan, India, and Ethiopia. Now it has become eurocentric to imply other countries did not experience a period that could be called a medium aevum or Middle Age.

So, once more, the simple answer is: (nearly) everywhere.

These were our most frequently asked who questions.

Check the table of contents to find other questions.

– advertisement –