MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The castle endures as one of the Middle Ages’ most recognizable icons. Its origins lie in turbulent times, and its dusk came from an evolution in the power structures that originally conceived it. Today, castles remain ubiquitous, from metaphors to global entertainment companies.

To understand the origin of the castle, we have to establish a definition of what a castle is. Often, the name is incorrectly assigned to other types of fortification. During the medieval revival of the 19th century, many structures were built somewhat resembling the aesthetics of castles, or idealized notions of them – a most famous example being Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany. In other cases, existing castles were improved upon, maintaining older buildings, but adding more modern ones in the same complex – Hohenzollern Castle being another German example.

Yet, most military historians define a castle as the fortified residence of a ruler. Therefore, not all forts are castles, nor were all the residences a ruler might possess castles.

The Middle Ages saw many sorts of fortifications come and go. As Roman forces retreated from most of Europe, locals flocked to abandoned Roman walled cities and forts – so much so, that every town in England ending with “-chester” was built in or around old Roman structures (named after the Latin castrum, meaning army camp). On the other hand, the Vikings built round forts with square structures within when wintering away from Scandinavia, from the Americas to Russia. There is evidence that Slavic peoples did so as well when fighting against the many Turkic horsemen invading from Central Asia between the 6th and 10th centuries.

Essentially, the castle concept was born in the context of constant violence. Early in the 8th century, the Caliphate‘s incursions into Spain, southern France, and southern Italy wreaked havoc amongst local rulers, indeed ending Visigothic rule in the former and precipitating centuries of conflict in the latter. Northern Europe, on the other hand, was immersed in internal conflict. The Franks spent much of the century trying to consolidate authority over their lands. Once Charlemagne came to the throne in 768, he spent considerable time fighting off different Germanic rivals – chiefly the Lombards and Saxons, albeit keeping internal order in his realm.

In the British Isles, many kingdoms vied for power, and towards the end of the century, most of northern Europe came under the Vikings’ relentless attacks. These began as small raids, but – by the middle of the 9th century – they had become carefully planned expeditions, involving thousands of men in dozens of ships.

Moreover, in Eastern Europe, the non-existent natural barriers allowed the Magyars to pass freely and ultimately settle in the Carpathian Basin, harassing and subduing many Slavic peoples along the way – not unlike the Bulgarians had done centuries prior, in addition to the constant pressure from different Turkic tribes.

The social context was equally complex. A socio-political system developed organically in Catholic Europe, whereby aspiring local rulers would pledge fealty as vassals to more powerful lords, exchanging different services (mostly of martial nature) for lands to support them, in a personal bond of honor and trust. The vassal would then fulfill his military services when called upon, and the lord would provide protection or address grievances when needed.

Later, in the 16th century, French lawyers called this system feudalism. It was more akin to a web of tangled loyalties rather than a strict hierarchy, whereby a lord would have many vassals, but at the same time, a vassal could have multiple lords.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

In the unstable environment of the early Middle Ages, lords and vassals alike started building castles. But these were quite different from the imposing stone structures we think of nowadays.

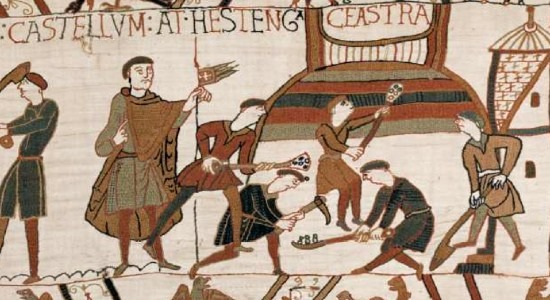

The simplest castle form was called “motte and bailey”. It essentially consisted of two wooden, often circular enclosures, one raised on a natural or artificial flat-topped mound. A tower-like structure was built on the mound, also known as upper bailey, where the nobleman and his household lived. Additional structures, such as stables, kitchens, or storage rooms were kept in the lower bailey – all made out of wood, with thatched roofs. Cheap, and easy to build, these primitive castles were everywhere in continental Europe, representative of the decentralized power structures in place, and the ever-present danger of raiders and invaders.

While relatively safe, the motte and bailey was objectively feeble and precarious at best. It was susceptible to fire and rot, and its limited space prevented it from stocking up for a long siege. By the very nature of its construction, virtually no examples remain, although some mounds have been preserved.

Furthermore, there exists the possibility that some of these castles were temporary residences or advance posts, but not much literature survives on these. Motte and baileys were popular into the 10th century, when they began to be replaced by the famous Norman keep.

Northern France was and remains a particularly rich and fertile region. Early in the Middle Ages, monasteries, and later towns, accumulated immense wealth – both in kind and bullion. The many rivers gently running through its rolling hills were a double-edged sword, though. They facilitated commerce but also meant that the Vikings, the scourge of the North Sea, were free to sail through them, in their shallow-drafted longships, laying waste and taking spoils on their whims.

In fact, the 9th century saw the Vikings perfect their strategies, going from small warbands to large armies numbering in the thousands. They managed to besiege Paris on a few occasions and raided practically every monastery, town and village in northern France. Their swiftness and unorthodox (to the notions of the day) tactics made them some of the hardest to fight enemies. Nobles throughout Europe had bought off Vikings many times, but that wouldn’t stop different chieftains from coming in and plundering as others did before.

Thus in 911, the French king Charles the Simple devised a brilliant strategy. After breaking the siege of Chartres, and chasing off a chieftain of the name Rollo, Charles offered the Viking an excellent deal. The king would give Rollo, essentially in perpetuity and for him to do as he pleased, the whole land between Rouen and the English Channel as a personal possession. In exchange, he only had to pay homage to Charles, convert to Christianity, and defend northern France from other Vikings. Fame and fortune being the principal motivators behind Viking expeditions meant that Rollo would therefore pass to history as one of the greatest chieftains of all, and could assure himself a comfortable living without the perils of raiding; the County of Normandy was born.

With the prosperity from his newly acquired demesne, Rollo took to appointing his own vassals from amongst his warband. His Norman subjects gradually took to building a new style of castle during the 10th century. In many ways, it was the natural step following the motte and bailey. The Norman keep was a bigger tower than the motte and bailey’s, built strongly enough to sometimes do away with the expense of walls altogether, and coalescing the functions of other buildings under one roof, but in different rooms.

While many keeps have survived to this day, most were lost to time. The vast wealth of Normandy allowed even minor nobles to erect their keeps out of stone, but archaeologists have recently suggested that the majority of keeps were likely made out of wood, surrounded by proper wooden walls, rather than weak palisades. It seems it was customary for both stone and wooden keeps to be painted with a lime whitewash which means it would have been next to impossible to distinguish the building material used under the whitewash. In contrast to the motte and bailey, foundations often had to be prepared prior to building the keep itself.

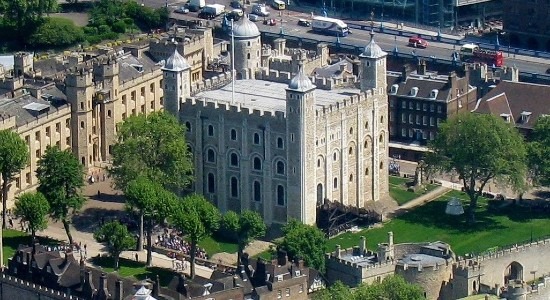

The Norman keep – or donjon in French (whence comes the word “dungeon”) – and its later iterations, was successfully exported by the Normans throughout the Latin Christian world in the 11th century, as Norman mercenaries fought and traveled throughout Europe and the Mediterranean. In fact, prior to the Norman conquest of England, there were about a dozen Norman keeps in England, belonging to Norman knights under the service of English nobles. Towards the year 1100, they became a staple in southern Italy, where a unique culture born out of Norman entrepreneurship – the Sicilians – came to be. Keeps came in many shapes and sizes, from ubiquitous simple squares, to the exquisitely finished, polygonal, Castel del Monte (literally Castle of the Hill), built by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in southeastern Italy. In the later 12th and 13th centuries, circular donjons became more fashionable, with Chateau Gaillard’s keep pioneering the shape.

Two or three stories tall, the keep became the fundamental piece of future castles. At its simplest, it was divided into a public area and private quarters. The keep’s walls, if made of stone, were measured in meters of thickness, which made windows generally difficult and impractical to construct, for they presented weaknesses both structural and defensive. The ground floor would feature a hall with a large fireplace, often shared with the kitchens, separated by a wall. The hall could also serve as a small chapel, and dormitory for servants or retainers, as trestle furniture was the norm. Contrary to popular belief, the interior of a keep was awash with color and art. Tapestries, embroideries, frescoes and wainscoting were widely used to decorate the interior of castles, with motifs ranging from biblical scenes to romanticized historical events. The coat of arms of the lord would have been on display in every public space, and rush mats would cover the stone or wooden floors – although rich lords could also have had tiling.

On the second story or higher, private chambers existed, at least for the lord and lady of the family, with the rest of the family sharing a room, and perhaps a bed – not unlike burghers living in townhomes. Privacy was as much a luxury in castles as it was in the cities, so even the most secluded rooms would usually house at least a handful of people. The noble couple may share the chamber with their young children (and their wet-nurses), servants, and guards. Powerful lords and kings, of course, could indulge in luxuries such as private rooms for every family member, even separate rooms for the lord and lady. In fact, in 1238, King Henry III of England avoided an assassin who snuck into his bedroom in the middle of the night; the monarch happened to be spending the night with queen Eleanor of Provence, in her room. As keeps and castles grew larger, however, more rooms were apportioned for specific purposes. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the castle of a magnate was, in practice, a small town of its own.

A habit that did not change from the early Middle Ages was for nobles to travel from one estate to another, whether of their own or for visiting other nobles. Furniture was thus made to be dismantled and moved around, even when at home. Tables and benches were set at the hall for most of the day, to be disassembled towards the night, and replaced with simple frames whereupon hay sacks were placed for the household to sleep in. On the other hand, the nuptial bed (or beds) was kept together until the lord and lady were to travel, and it would be reassembled at inns or the residences of other nobles.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

While a keep was the core of a castle, many other structures were needed to make it functional. Since there was a correlation between castles and martial duties, stables were needed, as most knights would have at the very least a handful of horses. On the other hand, storage facilities were necessary, in smaller castles to collect the tribute paid to the knight by the peasants living near his manor, and in larger castles to withstand sieges.

But as magnates grew richer, and castles bigger, change ensued. Wooden keeps were rebuilt in stone, as were the curtain walls surrounding the bailey, named enceinte (and particularly spectacular castles, like Dover Castle, had a double enceinte). Reinforced gatehouses were built, shut with thick wooden doors and reinforced with metal portcullises, a grid-like impediment. Towers, squared at first but circular later, were spread out at regular intervals, projecting forward from the enceinte to cover blind spots.

Most castles were also surrounded by moats, which could be wet or dry, and special gatehouses called barbicans were erected to guard the bridge to the main gatehouse. Dover Castle remains an example of a colossal freestanding keep, but some castles, like Monmouth Castle, incorporated the keep into the enceinte and raised a separate hall for daily living: the keep would be used as a backup in case of a prolonged siege. Other castles, such as a Caernarfon Castle, were erected with several courtyards, and the utility buildings were essentially embedded in the walls.

In a time when siege warfare was the commonest form of conflict, a castle’s security and safety went well beyond the thickness of its walls. It entailed a long betting game, whereby the besiegers would wager how long they could endure on the outside before they ran out of supplies or a relief army arrived, and how long the besieged could last with what they kept within. In the 13th century, the town of Monção allegedly broke a Spanish siege when a clever woman used the last wheat in store to bake bread, and tossed the rolls over the walls telling the besiegers “God has given it (sic).” The message (or ruse, in this case) was clear: supplies were plentiful enough to literally throw away, and the Spanish army promptly left.

For these reasons, castles were built near, around or on top of vital freshwater sources, like natural underground aquifers, or – when unavailable – wells. Supporting buildings were raised within the curtain walls, to minimize external dependence in the case of a siege. These could include:

This short list is merely exemplary of the essentials; castles could grow as large as needed in the span of decades, if not centuries. Malbork Castle, in modern-day Poland, covered an area of 21 hectares, the most of any castle on record, and allegedly housed 3000 members of the Teutonic Order; astoundingly, for its size, it was built as we know it today in less than fifty years.

The Age of Castles, if placed on a timeline, would range, in broad numbers, from the year 1000 to 1300. For a long time, the demise of the castle was attributed to the rise of firearms. At first glance, this rings true, for castle-building did dwindle as gunpowder weapons became more prominent. An oft-used example of the power of these inventions is the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, when the Ottomans‘ massive bombards incessantly pounded the city’s walls.

But this conveniently leaves out the fact that, after the Middle Ages, the art of fortification thoroughly carried on, evolved, and became more professionalized. In fact, in the 16th century, walls and towers were built with slopes and curves, respectively, to ensure cannonballs would skid over surfaces upon impact.

What ended the castle’s reign was the centralization of power in the hands of European monarchs, which in turn made the castle obsolete, as it quickly lost its military, political, and strategic importance. Moreover, in the 16th century, and following the examples of the Spanish Tercios, European kingdoms moved towards using professional armies, instead of the knights, levies and mercenaries of old; the fortified residences of nobles were thus replaced with forts.

French architects clung to the idealized castle and began designing country mansions resembling castles – or in French, chateauesque. The design was popular throughout Europe, as the nobles, rich as they’d always been, romanticized an era of more political power in the face of ever more autocratic kings. It was exalted in the 19th century’s Medieval Revival epoch, when European historians and archaeologists took a renewed interest in the Middle Ages and tried to dissipate the Modern Era’s mistaken views.

The castle permeated deep into popular culture, and have become associated with popular fast-food chains, video games, and, of course, Disney, as early Disney films were adaptations of children’s tales set in Germany or France, where the romanticized castle was as present as the noble prince or the damsel in distress. It’s spectacular to see how a millennium later, castles still besiege our imagination.

– advertisement –

Comments are closed.

Thank you for this informative site. I’ve been on the look out for such info.

You’re welcome, Gralion. We’re glad you liked it!