MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group on the island of Great Britain. They hailed from the continent and were ethnically Germanic. Their most important tribes – the Angles and the Saxons – mixed and intermarried with the original, Celtic inhabitants (the Britons) and the offspring of the Roman rulers. An interesting, hybrid culture thus sprang up on the isle. The Anglo-Saxons established the concept (and kingdom) of England, spread Christianity, and divided the land into shires.

During the Early Middle Ages (for Britain: 410-1066 CE), the Anglo-Saxons came under increasing Viking attacks, especially by the Danes. Still, when the Normans sailed from France and invaded England in 1066, an Anglo-Saxon king ruled over a large part of the island.

After a first attempt under Julius Caesar, the Romans invaded Britain properly in 43 CE. They ruled over the Britons for centuries, but gave up on the island in the early 5th century. Continental raids, stemming from the coastlines of modern Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands, intensified. With the central, Roman authority gone, tribes such as the Angles and the Saxons switched from reaving and roving to large-scale migration. Britannia thus became one of the first ex-Roman provinces that the Germanic invaders took over.

The Anglo-Saxons settled in villages inhabited by one or several extended families. These clans sometimes organized themselves into larger tribes. At first, there was no central authority to rule over these tribes, leading to continued yet small-scale warfare. Over time, particularly cunning and strong individuals distinguished themselves. They imposed themselves as cyning, or “the son of the kin” – the root of our word “king”.

So why exactly did the Celtic Britons and the Romano-British population allow these Germanic occupiers into their land? Well, the event was more gradual, harmonious and slow than often assumed. A lot of Anglo-Saxons were simply hired as mercenaries by the Britons, only bringing over their families years or decades later. Others received a plot of land like a vassal, rivaling their Romano-British landlord in prosperity and power only after centuries at best. On top of that, even Anglo-Saxon kings sported Celtic names well into the 7th century.

Although a lot of strife took place in “Dark Age” Britain, the identity of its Anglian, Saxon, Jutish, Celtic, Roman, Frisian, and Frankish inhabitants blended into an Anglo-Saxon culture through long centuries of intermarriage and assimilation.

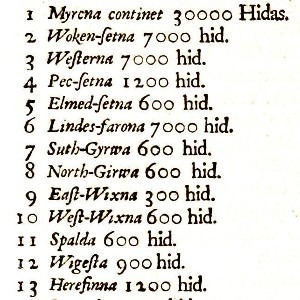

The Anglo-Saxons organized their society into ranks, with the cynings (kings) at the top and the ceorls or churls at the bottom – excluding villeins (serfs) and thralls (slaves). The ceorls (comparable to karls on the continent) were supposed to take care of a “hide” of land with their family. A hide later became a fixed unit of measurement but originally meant a plot of land that could sufficiently support a family. Since a ceorl had the right to bear arms, the power of the higher-ranking members of society was usually defined by the number of hides – and thus, churls – under their command. Religiously, Catholic monasticism swept in from Ireland and converted the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity.

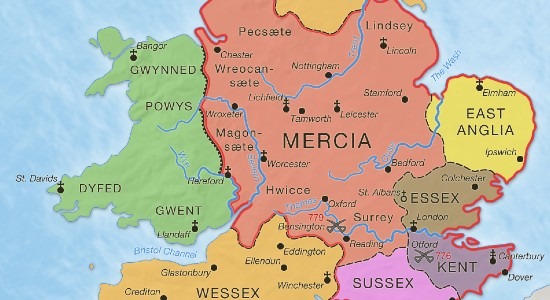

The competition between the various kings eventually led to the establishment of the Heptarchy. This is a modern term referring to the co-existence of seven, larger kingdoms – hepta means “seven” in Greek. These realms were East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. Their Anglo-Saxon heritage is apparent from their names: “Sussex” meaning Southern Saxons, “Wessex” Western Saxons, “East Anglia” Eastern Angles, and so on. The division was not as neat as it seems: many sub-kingdoms and states-within-states existed underneath the Heptarchy.

In a time when might made right, the Anglo-Saxon kings were eager to consolidate their power. During the 7th and 8th centuries, Mercia progressively dominated the other realms. Through merciless military expeditions, the Mercian kings brutalized the rest of the Heptarchy – going as far as taking London from Essex. The Anglo-Saxon culture and economy flourished in the meantime, though, as Britain remained in contact with the wider world. A Byzantine monk managed to become archbishop of Canterbury, whilst Anglo-Saxons imported Greek wine and olive oil and Frankish pottery and jewelry.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

From the 9th century until 1066, Anglo-Saxon England was constantly torn apart by successive foreign invasions. Despite the overbearing Mercians, the island was still divided into many kingdoms. This made it easy for the first Vikings to loot as they pleased, targeting the rich monasteries in particular. The success of the Northmen attracted ever more invaders from Scandinavia. In 865, the by-now christian Anglo-Saxons were attacked by what they called the “Great Heathen Army”, which conquered most of England.

The Vikings established a new realm, called the Danelaw – literally the area where the laws of the Danes were upheld. However, in the marshes and the woods, Alfred of Wessex assembled local militias and went on the offensive against the Vikings. He enjoyed mixed results but over time managed to assemble the Anglo-Saxons into one united front against the foreign invaders. He finally realized the dreams of generations of petty monarchs, becoming king of all Anglo-Saxons as Alfred “the Great”.

However, even Alfred did not manage to eject the Danes from England altogether. The island continued to suffer the beating of Viking raids, and none of Alfred’s successors was as strong or charismatic as he was. Many of them were forced to pay a special tax to the Vikings, called the Danegeld – “Danish money”. In 1016, the Danes even invaded England again in full force, incorporating it into their North Sea Empire.

Although it was short-lived, so too was the Anglo-Saxon resurgence that followed. The new king – the last Anglo-Saxon to rule England, Edward the Confessor – failed to produce a male heir. It prompted not one, but two foreign invasions in 1066.

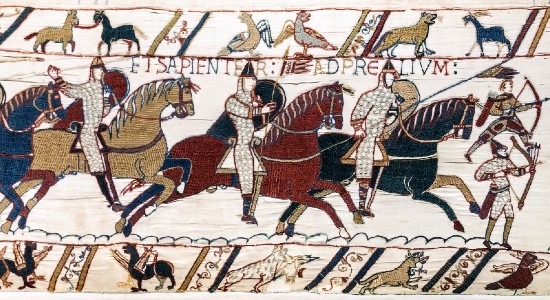

Edward’s brother-in-law led the defense of the island and managed to beat back the invading Norwegians. But within a month, he had to confront William of Normandy, who had launched an invasion as well, at Hastings. The Anglo-Saxon shield wall held for a long time but eventually gave way. An exhausted realm gave in after centuries of overwhelming foreign incursions: Anglo-Saxon England was no more. The Normans took over the island and their duke became known as king William the Conqueror.

With them, they brought French language, French culture, and – of course – the Norman keep. The Normans also violently removed virtually all Anglo-Saxons from positions of power. The number of deaths probably ranged in the tens of thousands. They couldn’t eradicate the Anglo-Saxon culture entirely, though. As the nobles and administrators spoke Norman French and the clergy used Latin, the common folk communicated in Anglo-Saxon for a long time after 1066.

In the 12th century, the Norman “high culture” and the Anglo-Saxon “low culture” mixed into a new linguistic reality: Middle English. Just like the Anglo-Saxons had fused with Britons, Romans and Jutes centuries earlier, they now mingled with their Norman overlords. This gave birth to medieval England, a territorial concept the Anglo-Saxons had first introduced to the island.

Over 25% of the words in the English language have Anglo-Saxon roots. The competition, as it were, between Germanic (Anglo-Saxon) and Latin (French) terms is still ongoing. A couple of examples:

Evidently, the culture of the Anglo-Saxons – or at the very least, their language – is still very much around.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports, reviews and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Grab a short intro on another civilization from our Medieval Guidebook.

Featured Image Credit: Ziko-C (Wikimedia)