MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

In typical modern representations of the Middle Ages, gothic architecture dominates skylines and cityscapes. The towering pinnacles of gothic cathedrals are thought to be as symbolic as gallant knights on bloodied battlefields, or stout castles on intimidating hilltops.

Yet all these examples only became widespread when the Middle Ages were already more than 500 years underway. More confusingly, the ancient people of the Goths were long gone when “gothic” cathedrals sprung up all over Europe.

How did such a massive misunderstanding come to be?

To be clear, the Goths as a people were not involved in the rise and spread of “gothic” architecture in any way. The Goths lived in the Early Middle Ages; their kingdoms lasted into the 8th century CE at the latest. Gothic architecture, on the other hand, only came around in the 12th century.

So why name these commanding cathedrals “gothic”?

As it happened, people living in later Middle Ages didn’t use this terminology at all. They referred to the new style as French, Norman, or – even more accurately at the time – “modern”. The nomenclature started to shift when 14th-century scholar Petrarca referred to the Early Middle Ages as a “dark age” because written sources from that period were so hard to come by. “Renaissance” thinkers after him started referring to the entire Medieval Era as the “Dark Ages” to underline their view of the period as an epoch of stagnation and underdevelopment. This contrasted neatly with their own “enlightened” era of the Renaissance and, of course, the historical period they were great fans of: Classical Antiquity, which preceded the Middle Ages.

This is where the Goths came in. As supposed topplers of the Western Roman Empire (hint: the real story was much more complicated), the Goths were seen by early modern academics as uncouth and uncivilized people. Before long, Renaissancist writers depicted the Goth as the archetypal barbarian that destroyed the ancient world to usher in the Dark Ages. Medieval cathedrals, as testaments to the presupposed ignorance and backwardness, were therefore in need of a new name. Early modern city dwellers could no longer rightly call them “modern”; instead, they referred to the buildings as “gothic” – a deliberate insult to the architectural style of the later Middle Ages.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

With regards to one aspect, Petrarca and his followers may have had a point, though. Between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE and the (literal) rise of gothic architecture in the 12th, one architectural style dominated most of Catholic Europe: romanesque architecture.

It received its name from its origins, as a natural progression of Roman architecture in the less urban environment of the Early Middle Ages. The main factor in the prevalence of romanesque architecture is that Roman methods of construction were reliable and well-known.

There still is much debate with regard to the first iterations of romanesque architecture. However, unlike gothic architecture, there is no discernible current, nor were there specific pioneers of the style. As such, common elements can be identified throughout all of Catholic Europe, during most of the pre-gothic period (we mean the architecture here, not the Gothic people). The result has been a situation wherein the romanesque style has been essentially attributed to a multitude of local flavors through the ages.

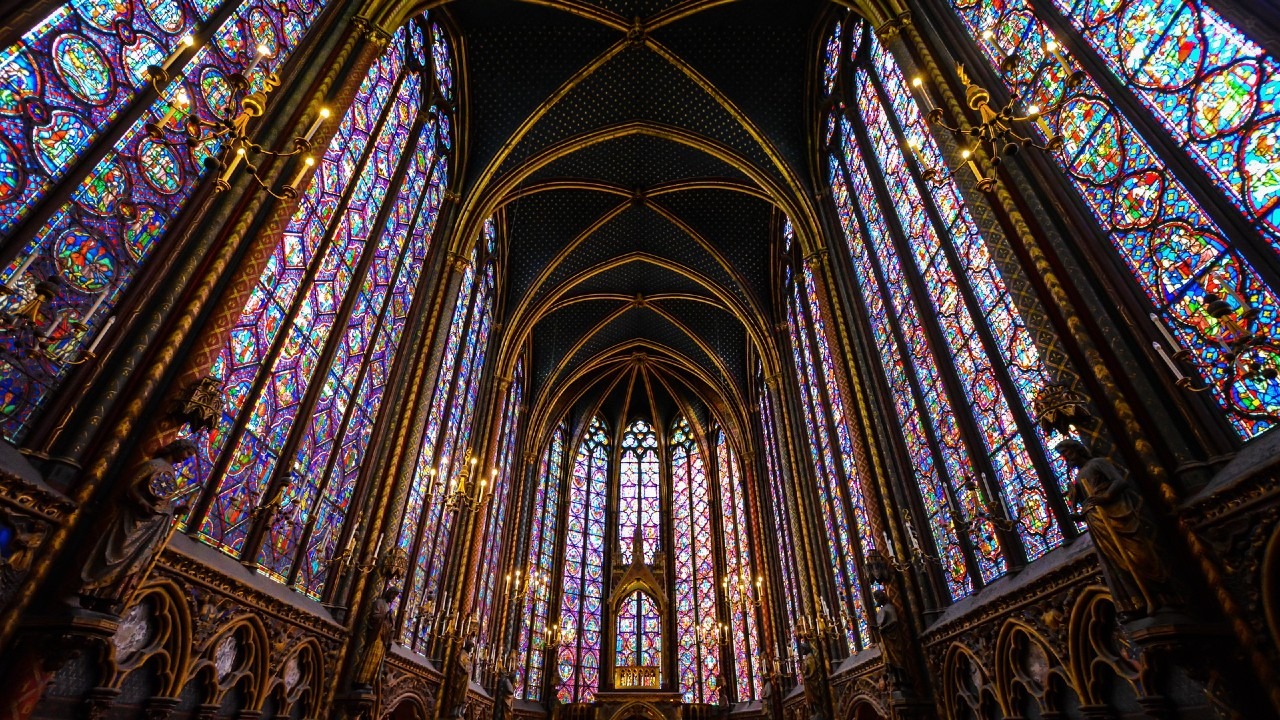

This is perhaps the only time we can rightfully refer to the Early Middle Ages as the Dark Ages. The common elements of romanesque architecture comprised massive walls that were able to bear the thrust from superior sections of a structure. This emphasis on sturdiness came at a cost; the few windows of a romanesque building were generally small, so as not to compromise the building’s overall integrity. It was, in essence, a technological limitation of the time, which resulted in dim interiors, nonetheless illuminated by rows and rows of chandeliers. For the same technical reason that romanesque structures had few windows, they also abundantly used round arches and stout columns; this was the only way that romanesque cathedrals could grow large – though they never did so as greatly as their gothic successors.

While a few elements that would later define gothic architecture were explored in the construction of English churches and monasteries around the year 1100 CE, it wasn’t really until a French abbot of the name Suger flipped the rules of architecture.

Born in 1081, and a member of the prestigious abbey of St. Denis (patron saint of France), Suger became its abbot at roughly forty years of age. Some years later, king Louis VI of France charged him with the task of renovating the basilica for the abbey, which had stood there for centuries, and now proved woefully inadequate for the importance of St. Denis for the French monarchs.

Suger first took at mustering funds for the renovations, which would eventually see the entire basilica of the abbey remade and would therefore cost a fortune. By pandering to a multitude of nobles, he was able to start the first remodeling stage in 1135; it would be decades before the church of St. Denis was completed in the gothic style. Soon after, churches, abbeys, and of course, cathedrals imitated the example set by St. Denis’s Basilica.

Early on, gothic architecture was restricted to ecclesiastic buildings, though its fundamental elements were borrowed by secular builders starting in the 14th century. These essential elements comprised:

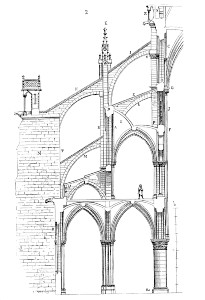

Another element generally associated with gothic architecture was added at the tail end of the 12th century: the flying buttress. A buttress is any section of a building designed to carry the weight of a building’s exterior walls and ceiling – it differs from a column in that it is embedded on the wall. (Romanesque buttresses were directly proportional to the thickness of the walls they were attached to – one more reason as to why romanesque structures are so bulky and colossal.)

The flying buttress had two architectural consequences:

The latter was important for christians, as the Gospel of John professed that Jesus was “the light of the world” – a statement that, as we shall see, medieval builders took seriously. All in all, these structural innovations allowed for the experimentation with gothic architecture, giving way to a wide variety of styles throughout Europe and the ages. These sleeker walls also allowed for the entries to cathedrals to become art pieces themselves, stacking multiple sculpted portals over the doors, main and secondary.

The construction of a gothic cathedral was costly in all manner of ways. Often, for example with the construction of the famed Notre Dame of Paris, a sizable share of the funding came from the bishop’s own pocket. In other cases, self-respecting kings and lords, eager to show their piety, would provide lands to the bishops or cash sums for the construction of the cathedral. Additionally, in a stroke of marketing genius, pope Urban IV authorized the sale of restricted indulgences (these were a remission of sins for the previous year) to help fund the construction of cathedrals.

The common man contributed his fair share too. Short pilgrimages saw the common folk travel to local cathedrals, where saints’ relics and other culturally relevant wonders would be shown as fundraisers of sorts. Souvenirs, in the shapes of tin, copper or bronze pins and brooches were sold as well. Another factor that stimulated non-nobles to give away their wealth directly to sponsor such projects was that the Bible stated that it was difficult for a rich man to go to heaven. (As always, there were different rules for the nobility, as they were already supposed to protect the Church.)

And then, there were guilds. Guilds were associations of men (and occasionally, women too) in the same line of work that banded together for mutual benefit, operating as a trade union of sorts – and a racket, to a lesser degree. They also had a bit of a mystical aspect of a brotherhood in the same trade, though this varied from a formality to a central element from guild to guild. Their number and prestige were directly proportional to the size of the town they were located in. Thus, as important groups within society, guilds generally contributed to the construction of cathedrals in money, services, or both, much like how modern-day companies sponsor charitable events.

In exchange, cathedral builders at times dedicated a window to show the activities of a guild sponsoring the construction of the cathedral – and as we’ll see, there was ample space to thank them. A secondary interest was that the courtyards adjacent to cathedrals were among the few safe public areas in a town or city. In Italy in particular, tradesmen and craftsmen alike gathered around the cathedrals, or in their courtyards, to conduct business. As such, the “cathedral district” became the focal point of not just religious but also secular medieval life.

However, regardless of how much money was raised, the construction of gothic cathedrals invariably took a lifetime at best. The money would often run out because the task was so monumental. Salisbury, in England, managed to set a record: its main structure was built in just 38 years – from 1220 to 1258. Still, further work took at least a decade more to “complete”, and its famous spire (the tallest structure in Europe at the time) wouldn’t be finished until 1320. The construction of the famous Notre Dame of Paris took over 180 years to complete, though admittedly, this was not a continuous process.

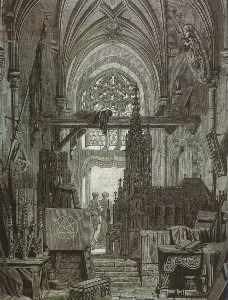

The (re)construction of a gothic cathedral was invariably done in stages. Usually, the first section to be built would be the nave – that is, the main area of the church itself. The raised ceiling would often show the ribbed vaults and have the space between ribs painted in a comparatively austere color scheme; a starry sky was a simple, yet stylish option. A choir renovation frequently followed suit – though this one would seldom show to the exterior. The transept, a section perpendicular to the nave was often the last bit of structural remodeling, if no new belfries or towers were designed.

To raise such structures, gothic architects literally used the romanesque results that predated them. A readily available source of stone, used throughout the Middle Ages, was the rubble of abandoned Roman buildings. As a matter of fact, the reason why the Colosseum looks the way it does today is that locals often just carved away stone needed for construction elsewhere in Rome – though there are no clues to suggest that there were concerted efforts to loot these places for materials; rather, it would have been “a happy convenience.”

An army of workers, some permanent, and some itinerant, would gather at the location of the project. The man in charge, the Master Mason – better known by his Greek name, architect – supervised all work. He would have started out as a regular stonemason, one of those to carve crude blocks of stone quarried in Caen, in northern France, a region renowned for its quality limestone, or perhaps the softer marble from northern Italy. The architect, which in the 12th century was almost always French, but by the 14th century was probably brought in from Italy, often negotiated an exclusive contract for the duration of a project. The symbol of his role was his gloves, which hung from his belt, to notate that his time of manual work had ended. Though most documents have since been lost, it’s clear that architects did draw plans: some sketches from the 14th and 15th centuries survived. As early as the 1220s, we can attest that architects were also building scale models before proceeding with a project.

The stone itself wasn’t as expensive as the shipping. Most projects using imported stone were completed on the banks of rivers to lower transportation costs; if unavailable, stone was sourced from local quarries. The price for ground transportation in the Middle Ages was almost consistently ten to twenty times as expensive as over waterways.

Because the main body and façade of gothic cathedrals were built almost entirely out of stone, stonemasons’ guilds became wealthy, prestigious, and deeply linked to the Catholic Church; modern freemasons’ brotherhoods do indeed trace their origin to medieval guilds. A medieval mason’s wage was paid based on however many stones he could carefully carve, which is why his initials were clearly inscribed on the stone’s top surface. This, alongside the solemn connotation that membership into stonemasons’ guilds held, and that stonemasons themselves were respected and well-paid craftsmen, suggests that these men were generally literate. Moreover, arrows indicated how the stone itself should be placed, as a mass of unskilled workers were burdened with moving the blocks around the construction zone.

While timber was structurally employed in the construction of cathedrals, in setting up supporting beams, frames, and arches, and even in elements such as spires, its main use was temporary. The construction of such titanic structures required multiple cranes, a network of scaffolds, stairs, ramps, and ladders. Sheds were also built to house tools and materials, as well as stalls for other services: temporary forges, commissaries, and shops of all kinds.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Metals were extensively used in the construction of medieval cathedrals, and it’s not hard to imagine in what capacities. The usual suspect is, of course, iron, given its durability, but a few others made appearances, albeit not in the same role.

Steel was not used for construction; the use of steel was primarily reserved for military hardware, and even then, it wasn’t until watermills were adapted to support bellows in the early 14th century that high-quality pieces exceeding a few centimeters in size could be reliably and consistently manufactured. Therefore, softer iron, which may have had a nominal degree of carbon in it, was used in construction, although at any rate, it wasn’t used for structural purposes to a relevant degree.

The realm of iron was overwhelmingly in the manufacture of nails and screws, and reinforcing fittings on other structures, such as tie-in iron rods being used for support. Furniture saw iron being used to fasten and fit the wooden structures, including chests and doors. On the human factor, we cannot forget to mention the tools of the trade: hammers and chisels, naturally, but also wedges were used throughout the construction process.

Next is bronze, a metal seen and heard by all parishioners in town. The bells in a cathedral were cast in solid bronze, and would constitute a significant expense. Previously, and especially during the Carolingian Renaissance, bronze had been used to cast doors. For example, the Augsburg and Hildesheim cathedrals (dating from the 9th and 11th centuries, respectively), both in Germany, feature gargantuan doors. But then again, romanesque architecture placed limitations on structures, and as such, bronze doors – given the metal’s softness – allowed for reliefs to be sculpted to portray biblical scenery. Again, fittings, chandeliers and candelabra of bronze – and copper too – adorned cathedrals from Scotland to Sicily. However, as gothic cathedrals arose, so did innovations in music – mechanical and theoretical. Massive pipe organs, cast in bronze as well, provided churchgoers with a multisensory experience when attending mass.

Lead was tremendously important for the construction of gothic cathedrals. It is a soft metal, as it melts at less than half the melting temperature of iron, but its density makes it excellent to provide rigidity for non-structural aspects of a building. In gothic cathedrals, these were to provide fittings for stained windows, roofing, and plumbing. It was through flattened bands of lead, molded to perfection, that the panes of stained glass were held together in the slender windows of gothic cathedrals. Likewise, lead tiles were used to ensure the roofs were sturdy, fireproof, and rot-proof. They would have been some thirty by thirty centimeters, hammered to wooden shingles underneath. In such capacity, lead was so valuable that when king Henry VIII of England closed the monasteries in the early 16th century, one of the first items he ordered confiscated were the lead tiles on the roofs.

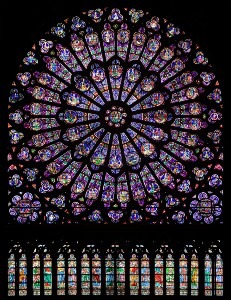

There are other, though less obvious uses for metals. Iron, our familiar fellow, was used as oxide ore to dye glass, giving a range of colors from crimson to pink, depending on the concentration and presence of other minerals. Cobalt oxide produced a heavenly blue hue, while manganese oxide presented a rich green tone. Glassmakers mixed these dyes while manufacturing the glass, providing architects with a vast range of shades to depict, more often than not, biblical scenery, but also scenes from nature, saints, and even the trades of the guilds that provided money for the project.

Due to the extensive use of glass, a new trend appeared in the second half of the 13th century; rayonnant designs. The name arose from the many “rays” that converged at the center of rounded feature windows, perhaps over the cathedral’s main doors, or at the transept. These rose windows, as they came to be named, were an explosion of stained glass and intertwined masonry that to this very day creates a formidable kaleidoscope for the devout parishioners within, or increasingly often, tourists with a fondness for history.

The newfound levity of walls and other structures in gothic architecture drove builders into design frenzies. By the 14th century, renovations were, or had been, undertaken throughout all of Europe – a trend that would repeat itself during the Gothic Revival of the early 19th century. Doorways, windows and walls were populated with the images of the apostles, Mary and saints. The flying buttresses were crowned with gargoyles, to ward off demons, and zodiac imagery. While this may seem like a contradiction, the astrological zodiac, with its menagerie of symbols, was not conflicting with the medieval cosmovision; if anything, it reinforced it, for it allowed to explain elements of the natural world in a way fitting to a creationist and more superstitious cosmovision.

Architects in southern Europe, where a stable and historically richer cultural tradition was present only selectively integrated elements of gothic architecture, never relinquishing altogether the old ways of Byzantine and Islamic construction – in fact, some have argued that elements present in Spanish gothic cathedrals are of Islamic extraction, not French. At any rate, this led to lovely architecture that reflects the blending of cultures that occurred in those areas.

Starting in the 15th century, elements of gothic architecture permeated into civilian construction too. In the Low Countries, for example, a century of explosive economic growth, partly due to the expansion of the financial industry, led to towns incorporating pointed arches and ribbed vaults in their designs. The ducal palace in Venice, on the other hand, thoroughly remodeled in the same century, saw an interesting mix of elements; the ground floor features a clearly gothic-inspired arcade, but the uppermost level is reminiscent of the Roman shapes and designs.

Though gothic architecture was vilified and left behind during much of the Modern Era due to its innate link with the Catholic Church, the rise of nationalism in the late 18th century had people trying to connect with their historical roots. The imposing medieval structures, at times victims of time but more so of iconoclasm (looking at you, French revolutionaries), were the perfect time machine for the casual observers to evoke their countries’ old glories. From symbols of ignorance, the gothic skyscrapers became once again a pinnacle of civilization.

In the same vein, the 19th century also saw the renewed construction of gothic structures throughout Europe. But their magnificence was promptly outclassed elsewhere; to this very day, the New World features some extraordinary gothic edifices, such as St. Patrick’s cathedral in New York City (built between 1858 and 1910), and the church of St. Francis Borgia in Santiago, Chile (built between 1872 and 1876, alas a victim of arson during the 2019 riots). Finally, it has also been suggested that gothic architecture was influential in the Art Deco style – and the connections are definitely there, with sleek and elongated lines pointing upwards.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Comments are closed.

Hello. remarkable job. This is a impressive story. Thanks!

Thank you so much, Weidmann!

I like this internet site because so much useful material on here : D.

Wow, Muckel! We’re so glad to hear that.

I like this blog its a master peace ! Glad I noticed this on google .

Thanks a lot, Hogle. We’re glad you noticed us, too. 😉

It is truly a great and useful piece of info. I’m glad that you simply shared this useful info with us. Thanks

We’re glad you enjoyed the read, Kaili. Thank you!