MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The evolution and constant improvement of the rural roots of medieval economies allowed for the birth and growth of the financial industry. A few centuries of fallow and development thus set the foundations of banking as we know it today.

It is often assumed that the collapse of the Western Roman Empire brought about a transversal recession in Europe, from the existence of centralized government, to urbanism, and of course, economics. There is some truth to that. Roman rule had facilitated commerce and created a set of infrastructure, legal and physical, to connect the continent and maximize military efficiency. Roman legionaries, being professional soldiers, received a standardized, steady pay, in the form of a silver coin known as denarius (pl. denarii.)

It is here where we must mention that throughout history, coins have served a dual purpose. The most obvious, of course, is commercial. Instead of bartering, these tokens allow their holder to transact value, for goods or services. The other purpose is symbolic. Through seals and inscriptions, coins serve to remind the people using them who holds power.

The presence of legions throughout Roman Europe proliferated the use of the denarii among the locals – and with foreigners too. Roman denarii have been found in modern-day Poland and Sweden. This supports the notion that Germanic tribes would accept Roman coins and use them to trade with their eastern and northern neighbors as well. As the legions withdrew, though, and as provinces fell under the rule of Germanic kings and chieftains, the amount of newly minted coins diminished accordingly.

On the other side, though, there are clear exceptions to the assumption. First, in the wake of Rome’s collapse, there emerged solid kingdoms in current-day Italy and Spain. Under the guidance of Gothic monarchs, the kingdoms in these peninsulas kept some of the government structures founded by the Romans. A noteworthy example is that Ostrogothic king Theodoric struck gold coins with his name and face, much in the same way his imperial Roman predecessors did. Furthermore, it is imperative to remember that a string of conquests in the 6th century brought many former Western Roman provinces back into Byzantine rule. The Byzantines also promoted and supported the use of coins in the Balkan peninsula.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

A change in lifestyle was the major cause for a stark reduction of newly minted coinage in Western Europe. During Roman rule, there were many prosperous towns that favored dynamic markets; at its zenith, Roman London’s population may have exceeded fifty thousand inhabitants. Fields were worked by slaves, in a business operation inextricably tied to Roman towns. The political instability that followed the collapse of Roman authority, however, led to major displacements of people throughout Europe to rural areas. Archaeological finds in England and France have established that for nearly two hundred years after the fall of Roman rule, most settlements consisted of at most, a few hundred people.

This separation of communities, as well as the reduction in population due to the waves of epidemics and internecine warfare, pushed most inhabitants in any given settlement to work into self-sufficiency agriculture. Commerce never really disappeared, but it was reduced in scale so drastically that it might as well have died, notably because most transactions reverted to barter, a system where goods or services were traded directly, with no form of currency to stand in for either.

Furthermore, agricultural technology hadn’t much advanced since Roman times, and it would not be until the late 7th century that communities were able to diversify labor more easily, and thus promote economic growth – which roughly coincided with the solidification of the Kingdom of the Franks, and the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

As is in many instances of medieval history, we can attribute the resurface of coinage to Charlemagne. As part of the many reforms instituted by him, the standardization of currency was significant. For the first time in centuries markets grew, both in abstract and physical terms. Chiefly, Charlemagne reinstituted the silver denarius (in French, denier) as what came to be known as the Aachen penny, and gave it a specific silver content per coin, oscillating between .94 and .96 silver purity in modern standards. Two hundred and forty deniers constituted a libra (the Roman pound.)

The denier system swiftly spread through continental Europe in the 9th century, both as an accepted currency and as a reliable monetary structure. Within a century, the Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia, Offa, famously copied Charlemagne’s Aachen penny. From there it trickled down to other kingdoms. Further copies and adaptations of the penny were used in Spain (as the penique) and Germany (as the Pfenning) – Italy was a bit of an outlier here for reasons to be explained,

Yet even as political structures solidified in Western Europe, the penny as a coin was prized mainly for its silver weight, rather than any attributable monetary value. Essentially, this meant that transactions were based on however much silver was contained in the number of pence, rather than a fixed amount of coins. It wouldn’t be until the 12th century that such changes took place. Thus, in many cases, bullion – that is, refined precious metals in uses other than for currency – was employed whole instead of striking coins.

Two famous examples come from Northern and Eastern Europe. When raiding or trading, Vikings seized mountains of goods made of gold and silver. They would then use that as currency without necessarily striking coins for that purpose. Indeed, sagas speak of great chieftains gifting gold and silver bracelets to prospective fellow raiders, both to show off and, in a way, to buy the men’s loyalties. In Novgorod, and the Rus’ principalities in general most goods were traded in furs – the main commodity exported by the region – but the highest currency denomination were silver rods known as grivnas.

There were two major factors that promoted growth and increased economic activity in the Middle Ages. First, there was the appearance of heavy plows, around the turn of the millennium. Able to dig deeper, these tools allowed for ever-growing crop yields, the foundation of medieval economies. On the other hand, power was better consolidated by magnates during the 11th century. England, for example, was unified under a single, strong monarch. On the continent, the previous threats of the Vikings from the north, and Magyars from the east were consolidated into Catholic kingdoms. While not a perfect arrangement, as violence and warfare never really stopped, the reduction was noticeable enough to ease a path for economic progress.

The latter factor can be best observed in the aftermath of the First Crusade. The establishment of Catholic principalities in the Levant permitted more mobility between Asia Minor and Southern Europe. While commerce between Europe, North Africa and the Middle East never really stopped during the Middle Ages (the Italian city of Amalfi being a commercially prominent city centuries before being dethroned by its northern rivals), this political configuration made it possible for European merchants, to reliably source luxury commodities, and sell them at spectacular profits back in the continent.

The scale of this evolution is extraordinary. The 11th century had seen the rise of towns all over Europe, as buoyant villages were enriched by an ever-increasing focus on local, profitable commodities. From a few hundred inhabitants, these settlements grew exponentially, and by the 13th century, Europe was dotted with towns numbering a few thousand inhabitants within their walls – Paris, particularly, surpassed the 50,000 inhabitants towards the year 1300. Markets became ever more integrated and efficient. One could even say that the 13th century saw the professionalization of the merchant-financial class.

As agricultural yields improved, lords – or their stewards – took the surpluses to the nearest towns, and sold them. That way, cash flowed from towns into the countryside. In the 12th century, many feudal dues, such as the fruits of the labor tribute owed by peasants to their lords of the manor, or even military dues owed by vassals to their feudal lords, were replaced by cash payments., the latter coming to be known as scutage.

Burgers, that is, people living in towns, grew richer by the day. Whether it was by selling English wool in Flanders, wine from Bordeaux in London, or Byzantine silks in Italy, they quickly amassed tidy fortunes. In northern Europe, the Hanseatic League emerged, as an association of German towns that joined forces, easing tolls and facilitating commercial cooperation, as well as providing lodgings and trading posts to German merchants (the so-called kontore) in towns outside the League. Around the Mediterranean Sea, the Italians created similar institutions. From Constantinople to Alexandria in Egypt, the fondachi allowed Italian merchants to trade and travel, safe from physical as well as commercial harm. These establishments obtained legal privileges in whatever towns they were in, as the latter had major financial incentives to keep them.

As these merchants traveled, however, a new need appeared for them.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

As discussed, the Aachen penny and its imitations circulated widely throughout Europe. But the lack of a centralized European authority and the rise in competition between towns and cities made it so that by the 13th and 14th centuries currency became a bit of a problem.

Exceptionally, the kings of England had been able to somewhat standardize currency within the realm, partly due to the government structures existing prior to the Norman conquest, and partly due to the geographic barrier that the English Channel is, restricting the flow of goods and people. Such is the case that as early as the 12th century, English kings would grant nobles the right to strike coins, a process whereby bullion would be taken to a mint and shaped into coins – a medieval take on “printing one’s own money.”

Everywhere else, though, currencies were local, and their usage seldom extended beyond regional borders. In 13th century France, for instance, virtually every major magnate would compete to promote their own penny standard. Nobles in Chartres, Tours, and Tournai minted their own silver pennies in a financial free-for-all. Two were more prominent: the Parisian penny and the denier de Provins, both being relatively stable. The former had the backing of the king of France, and the latter had the benefit of being the currency of the fairs of Champagne, the foremost commercial institutions of the 13th century.

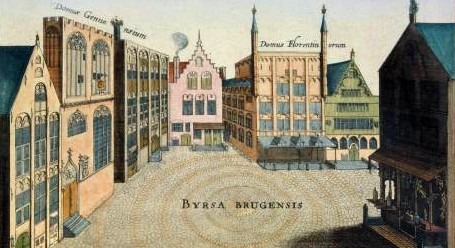

Fairs had gained prominence throughout Europe towards the year 1100 and gradually became systematic cycles over the course of the century. They were itinerant instances of commerce, facilitating the congregation of international merchants and further accelerating an economy that increasingly relied on the trade of manufactured goods, chiefly textiles. These were truly international instances, with merchants from York, Stockholm, Florence, Barcelona, Constantinople and beyond, gathering under circumstances engineered to conduct commerce. Banks were thus a natural development of the growth and interlocking of regional markets.

The etymology of the word “bank”, both in Germanic and Romance languages derives from terms associated with benches. Early bankers would literally set up benches and tables at city squares, or shops if they were more consolidated, during market days or at fairs, and promote their financial services. The knowledge of early banking lay in the understanding of exchange rates, which could fluctuate based on a plethora of factors. The main problem was that coins could be debased, meaning that the overall content of silver in the alloy was reduced, or outright broken into pieces. Both were major offenses under jurisdictions throughout Europe, and at the very least, they would land the accused hefty fines.

Even seemingly small locales were financially active to the degree that they featured at least a dozen or so moneychangers. In the lesser-known city of Pistoia, in Italy, for example, in the year 1257, the square near the cathedral housed some nineteen moneychangers. Florence, in the early 14th century, on the other hand, had created a dedicated forum for international trade, the Mercato Nuovo (New Market, in English) with the bankers at the forefront of the commercial space.

The matter of loans in medieval Europe was deeply restricted by religion. It is often said that the Catholic Church did not allow for-profit lending. The reality is that it did, but it capped interest rates at 5%. Anybody charging more than that was guilty of a sin called usury. When factoring in risk, competition, and so on, this legal framework made lending a generally poor financial approach – for Catholics, at least.

Jews were outliers in the traditional order of medieval society, by virtue of their religion. They could not participate in the clergy, obviously, but they could not become a part of the feudal hierarchy – as all nobles ruled under Catholic kings. They were, however, quite active in the cities of the eastern Mediterranean, chiefly as physicians and traders. Hence, when the European markets began to expand, throughout the 11th century, many Jews migrated into the continent, settling in the Rhineland from the year 1000 onwards.

Given this legal vacuum, Jews were generally free to practice moneylending, as to them, lending to powerful borrowers was a safe business strategy. Sadly, antisemitic sentiments in Europe, only exacerbated by the venomous rhetoric of Peter the Hermit, caused major pogroms in the aftermath of the First Crusade. Thereafter the Jewish population was generally looked down upon. Many Jews relocated to Eastern Europe, but those who remained in the West continued with financial businesses.

Despite a layer of animosity towards Jews, towns recognized the crucial financial value their services provided and thus granted them protections under the law, as well as the right to a certain degree of self-governance. The city of Troyes, for once, had a well-defined ghetto, from where the Jewish occupants were mostly free to conduct business, administer their own law, and protected from outsiders by city authorities if needed.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

The Jewish influence grew throughout the continent and eventually, both the kings of England and France were deeply indebted to Jewish lenders. Philip Augustus of France went as far as expelling the Jews in 1182 to escape the Jewish banker’s pockets – they were a force unable to retaliate in any way. In a toxic cycle of extortion, king Philip would invite them back, and then exile them again, on several occasions during his reign. Edward I of England was no different, expelling Jews from England altogether in 1290. It would be over 350 years before Jews could freely live in England again.

On the other hand, were the Templar Knights. Originally an order of warrior monks to protect the Temple of Jerusalem, this brotherhood quickly gained power beyond the sword or the cross. Becoming a Templar knight was a highly respected role in society, for it merged the military and clerical roles that noble-born men were expected to fill, and it was typically befitting of the younger sons of a noble to join their ranks, accompanied by well-desired grants of land or cash payments.

This combination of continuous growth in capital due to the very nature of their social composition, and the presence of well-educated, cosmopolitan men led the Templars to quickly amass a fortune, trading grain and generally carrying out businesses throughout the Mediterranean. Their operations were not for profit per se. Their earnings served charities, financed the upkeep of the order’s properties, scattered throughout the Mediterranean world, and helped pay for expeditions when needed.

As it happened, they loaned to kings too. A later French king, ironically called Philip “the Fair”, was one of their frequent customers. In an astute move to escape the debts he had incurred, on Friday, October 13th of 1307, he declared the Templars to be heretics (among many other accusations), had their leadership arrested, and burned at the stake, thus doing away with his creditors. Incidentally, Pope Clement V posthumously absolved the Templars the following year, but the order was practically destroyed. Some of its remaining members joined other organizations, like the Hospitaller Knights.

The evolution of medieval finances never stopped; rather, one could say it only accelerated as the period moved on.

While up to the 13th century most currencies were a variation of a silver coin, towards the year 1300 more and more gold coins appeared. Previously, the gold supply was rather limited, and consequently, a single gold coin was overvalued for most markets. But as the 13th century progressed, and as economies grew, the market forces led to the propagation of gold coinage.

The usual suspects came from Italy. The port city of Genoa started minting the genovino, soon followed by the florin, from Florence, and eventually the Venetian ducat in the 15th century. These were everyday conveniences, though, akin to carrying €100 notes nowadays. For merchants and bankers dealing with bulk shipments of spices, gemstones, and ells of luxurious clothes in markets across Europe and the Mediterranean world, carrying several pounds of precious metals was not only dangerous but counterproductive.

But bankers were ahead of this, of course. Already in the 13th century, bankers had established dedicated networks throughout Europe, with subsidiaries facilitating the transfer of large sums – and speedy couriers to assist them. In Flanders, a courier service between the fairs of Champagne and Ghent covered a route over 300 kilometers long in four days.

Merchants, however, could just hold onto this sort of paper money themselves. For example, if a merchant from Barcelona wanted to buy English cloth-of-gold from a Flemish merchant in Florence, the former could write a cheque, instructing his bank in Brussels to transfer an agreed-upon fee to the Flemish merchant’s account in Brussels. The Spanish merchant would then go back to Barcelona with his cargo of expensive fabrics, and the Flemish merchant would get back home, carrying the cheque with the instructions for the banks to complete the transfer.

Towards the 15th century, this sort of banking had become commonplace. Merchants and rulers alike would keep open balances throughout Europe, to guarantee access to their accounts. While they backed their accounts by mighty financial assets in bullion and goods, nobles tended to do so using their lands.

Cheques, and other financial instructions, could be made to the carrier or specific people. Bankers were able to extract profit from these transactions by charging fees on withdrawals, transactions and, most importantly, when exchange rates were involved. A well-managed combination of financial services was bound to prove a bottomless well of wealth.

It comes to no surprise then that northern Italy (at the time known as Lombardy), with its great variety in currencies, became the capital of European banking, and soon enough, the richest region of Europe. One key advantage that Italians had over most Europeans was that they were early adopters of the decimal system and Arabic numerals, which, in contrast to Roman numerals, greatly facilitated arithmetic – a crucial tool in the financial industry.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Beginning just prior to the Black Death in the 14th century, and throughout the 15th century, patrician bankers in northern Italy consolidated power. Towards the year 1500, a dozen or so families controlled the financial industry in Lombardy, headquartered in Milan, Venice, and Florence. From that point in history, banking grew exponentially.

The Italian Wars, beginning in 1494, provided massive opportunities, both financial and political, for Italian bankers. The decades of continued military conflicts throughout Europe required steady funding, secured from Lombardy. While Venice and Genoa maintained maritime commerce as their main sources of revenue, banking had become the economic keystone in Florence, under the grasp of the Medici family. They were the ultimate survivors and reapers of the banking sector in Florence, after the demise of the Bardi, Scali and Strozzi families – the latter’s fall orchestrated by the Medicis.

Throughout the 15th century, and particularly after the Fall of Constantinople, which cut off easy access to sought-after Asian goods, Portuguese expeditions towards East Asia were fueled by Italian loans. Into the 16th century, further business opportunities presented whenever Spanish conquerors readied expeditions to the Americas, as they were required to shoulder the costs by themselves – the noble names of their leaders often being the only leverage they could muster in the face of potential lenders. European banks thus became global institutions.

Thereafter, the banking industry only grew larger and more complex. It was broken free of its canon law chains in Northern Europe with the Protestant Revolution, which saw good businesses as desirable to God’s sight. It further became a scientific enterprise in the 17th century, with mathematicians working for banks, engaging in complex arithmetic to ensure continuous profitability, which was complemented by the rise of stock exchanges in Amsterdam and London. Today, the legacy of medieval bankers lives on in places such as Hong Kong and New York.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports, reviews and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Comments are closed.

I am visiting this web site regularly, this site is truly good

Glad to have you, Candace. Thanks a lot!

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website

yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz reply as I’m looking

to construct my own blog and would like to find out where

u got this from. thank you

Thanks, Emilie! I created this site myself but I did use the Blocksy theme. Be sure to check it out. You can edit almost anything the way you see fit and most of its features are free. I wish you good luck with your blog!

Your means of telling all in this post is truly amazing, Thanks a lot.

That’s so kind of you to say, Nichole. Thank you for your comment!

I have been exploring for a little for any high quality articles or weblog posts

on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this website.

Studying this info So i’m satisfied to I discovered exactly what I needed.

I so much definitely will make sure to do not put out of your mind this web site and give

it a look regularly.

So glad to hear we were able to offer what you were looking for, Tomoko. Do visit again anytime!