MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

One of the more popular misconceptions about the Middle Ages is that people only really knew the world immediately around them – and that, by that token, they thought the world was flat. However, both classical testimonies and the experiences of medieval people go a long way to refute this thesis. Especially the Silk Road, a commercial route from China to the Mediterranean Sea, is a case in point of how the medieval world was well-connected.

During Late Antiquity, “Asia” was generally understood as a Roman province, roughly corresponding with modern-day western Turkey; other regions in what we now know as Asia Minor had their own names. This localized naming custom persisted during the Middle Ages, partly because – beyond a certain distance – the medieval world was engulfed in the shadows of third-hand knowledge. Nevertheless, Pliny the Elder, living in the first century CE, seems to have been the first to use the name for the whole landmass east of Asia (the province.) For the sake of this article, though, the term Asia will refer exclusively to our modern understanding of it.

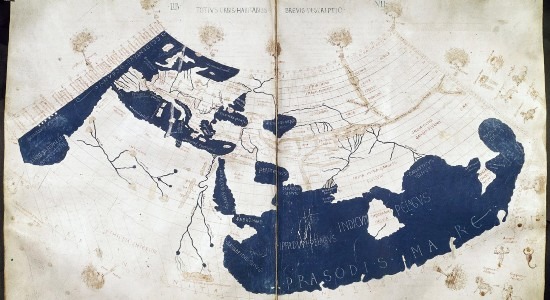

Through third parties, the Romans had been in steady touch with the Levant for centuries prior to conquering Asia Minor. Persia and beyond were well known and understood, mostly due to Alexander the Great’s ephemeral conquests, which stretched as far as modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan – the latter known then as Bactria. As a matter of fact, Greco-Roman scholars were aware of the existence of India, and had accurate notions of what Central Asia was. In the 2nd century BCE, socio-political conditions all throughout the continent favored the establishment of the Silk Road, which turned out to be the most important commercial artery on earth until the late 15th century, when European attention started focusing on a brave new world. Far beyond Bactria and India, however, where there may have been dragons, were Serica in the north, and Sinae in the south.

Serica was in what we now know as north-western China. The Greco-Romans were in contact with their inhabitants, the Seres. The nature of these peoples remains a mystery for two reasons. For once, Serica was not well defined in terms of geographical boundaries; our current comprehension of it is based on approximations, which ties into the second point. At the time, the area might have been populated by a variety of peoples, from the Indo-European Tocharians to proto-Turkic tribes. There’s also the possibility that these peoples were governed by Han Chinese administrators. Unfortunately, there is no conclusive evidence that favors either of these hypotheses.

As for Sinae, it is easier to align it to present-day south-eastern China, both through the self-evident linguistic root of the name, and because the most expedient route was through the sea, an avenue that was cheaper, safer, and quicker than the overland route, and that had been developed by traders all around the Indian Ocean’s basin.

At any rate, Europeans during the Early Middle Ages had some awareness of Asia Minor, as the growth of the Catholic Church meant that at least once a week, communities would gather to hear readings from the Bible – which narrated events happening in Egypt and the Levant, as well as correspondence with peoples living in what was then the Byzantine Empire. The knowledge of India, Persia, and adjacent realms, though, was unavailable to most Europeans between the 4th and 12th centuries. Scholars living in the Islamic caliphates preserved it, and during the time they kept steady contact with cultures within the Indian Ocean’s basin, including Eastern Africa, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia – which explains why the latter nowadays hosts the greatest number of muslims in a single country.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

A firm European presence in Asia Minor was the norm well into the late 13th century. The Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, and ultimately Catholic rulers, occupied regions within Asia Minor in a near-continuous fashion. The Byzantine Empire held northern Egypt, the Levant, and territories nearing the Caucasus Mountains – territories that had been conquered by the Romans of classical times – well into the 7th century CE, when they were lost to the swift expansion of the Rashidun Caliphate. Even then, the expansive plateaus of Anatolia were kept by the Byzantines until the year 1071, when the Seljuq Turks soundly defeated Romanos IV Diogenes at the Battle of Manzikert, effectively losing the provinces that had been in Roman hands – one way or another – for over a thousand years.

But this absence of European rulers was not to last. In 1095, Pope Urban II instructed faithful christians to “undertake this journey [what would become the First Crusade, red.] for the remission of your sins, with the assurance of the imperishable glory of the kingdom of heaven.” After a quick succession of conquests throughout the Levant, Catholic leaders reimposed their authority throughout the region, founding the Crusader States – also known as Outremer. Among the many complex causes of the First Crusades was the difficulty that christian pilgrims faced when traveling to the holy places of Christianity. Pilgrimage, while not vital, was considered of great importance for medieval Catholics, as through the risky and significant investment in time and financial resources, christians could provide concrete proof of their devotion to God.

The German Pilgrimage of 1064 can attest to this. Spearheaded by archbishop Siegfried of Mainz, it was probably the largest single European pilgrimage into the Holy Land before the First Crusade. This exceptional endeavor saw around ten thousand people eagerly march from Germany to Jerusalem, as many others had done before them. While the journey seems to have been mostly uneventful, after exiting the Byzantine realm near present-day Iraq, the pilgrims were attacked and harassed on multiple occasions by locals under Abbasid rule – albeit it is unlikely that they did so under their ruler’s commands. Back in Europe though, this was deemed a direct, organized aggression to christians at large, reinforcing militaristic notions established in the Council of Narbonne, a decade earlier, that christians were a Host of God, and thus should fight against ungodly foes.

It is easy to assume that the intermittent lack of European leaders in the Near East meant an absence of Europeans altogether. This could not be further from the truth.

Certain Italian cities maintained steady commercial and political links with the Middle East (as it is known today). Well into the 11th century, the southern Italian city of Amalfi dominated Mediterranean trade coming off the Silk Road, flowing into Europe. Additionally, in 801, Genoa received the Carolingian ambassador that Charlemagne had sent to the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid. His name was Isaac Judaeus, and his mission was to establish amicable links between Aachen and Baghdad. He succeeded and, on his return, he brought a gift from the caliph to the emperor, an elephant of the name Abul-Abbas.

On the other hand, between the 9th and 11th centuries, traffic in the Russian River System intensified, and intertwined with waves of steppe invaders, thus giving root to the approximate social situation that we see in Europe today, as the Rus’ arose as a civilization of their own, and the Magyars settled in the Carpathian Basin. This also facilitated contact between northern Europeans and Caucasian peoples. Scandinavian presence on western Caspian shores is firmly recorded as early as the 860s, fighting against the Khazars along the Volga’s banks, and bringing luxury commodities from the Silk Road. Harald Hardrada for instance, a chieftain who would become king of Norway and die at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in an attempt to seize the English crown, boasted of traveling to Jerusalem in the 1030s, whilst in service of the Byzantine Emperor. The Vikings even had their own name for Constantinople: Miklagard, or “the Great City.”

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the boundaries to most reliable European testimonies in Asia lay a few kilometers east of Jerusalem, and on the eastern coasts of the Black Sea. The visitors were mostly Rus’ and Italian merchants, who thanks to a stable political environment could conduct business with far fewer problems and threats than their ancestors ever did.

The Italians had developed a system of commercial embassies of sorts, called fondachi. These institutions allowed them to rest and resupply during long commercial voyages. The three most important ones were for purchasing grain and slaves in Kaffa, in the Crimean Peninsula; gems and spices in Acre, a short trek west of Jerusalem; and everything at once in Constantinople. The common thread was that these cities were at the western ends of the Silk Road.

Italian merchants were but the last of a multitude of middlemen in the world’s foremost commercial artery, one that had endured since before Julius Caesar, and that only really lost prominence after Europeans conquered the Americas. Whether by sea or land, it spanned over 8,000 kilometers as the crow flies, encompassing the largest share of global commerce until the 16th century. Therefore, there were great economic incentives for the end merchants to cut off as many of these resellers as possible, and greater yet for an empire to seize the Silk Road altogether.

Marco Polo’s tale is the one that ties these threads together.

The Mongol Empire had humble roots. It started out in the last decade of the 12th century, when a man in the Mongolian steppes managed to unite all the Mongol tribes under one banner. Temujin, as he was known, was already in his forties, which in the steppes meant he was nearing the dusk of his life. His initial achievements subduing neighboring steppe horsemen befitted him the epithet “Genghis Khan” (although current scholarly consensus has shifted to the more accurate Chinggis Khagan), or the “Universal Khan”, the latter term being a transversal title for steppe rulers, first used by a Turkic khaganate in the 4th century CE.

Thus began a brutal career of conquest and genocide. The Mongols were a minority in the steppes, as these lands were dominated from the Caucasus to China by Turkic peoples. Through diplomacy, but more often than not, sheer violence, the Mongols placed nearly every inhabitant of the Asian steppes under their domain – save for those far up north in Siberia. One of the many entities that the Mongol Empire absorbed was the Tatar Confederation. The Tatars were one of the several Turkic horsemen inhabiting the steppes at the time. They are particularly important to Marco Polo’s tale, as he refers to the Mongols as Tartars – a play on words referring to the destructive and apocalyptical nature of Mongolian expansion, and the Greek word tartarus, the deepest level of hell.

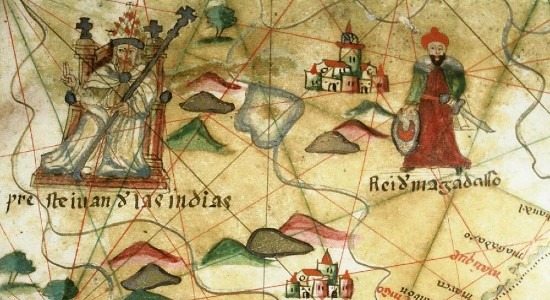

By 1279, the Mongol Empire controlled current-day China, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, the Korean Peninsula, and every modern state between Siberia and the Indian Ocean. In essence, they had come to monopolize the land routes of the Silk Road. Although by the time Marco Polo ventured to the Far East the Mongol Empire had split in four, its pieces remained stable and safe enough to stimulate trade on unprecedented levels; this is perhaps one of the reasons why Niccolo and Maffeo Polo, Marco’s father and uncle respectively, decided to travel by ways of the Silk Road. They met and befriended one such Kublai Khan, one of Genghis Khan’s many legitimate grandchildren. He was the one who completed China’s conquest and established the short-lived Yuan Dynasty. Although Kublai had set out to conquer China from Karakorum, deep within Mongolia, upon subduing the Chinese, he promptly established court in the city of Khanbaliq (modern-day Beijing), and was quick to adapt many cultural ways of his newfound subjects, from dress styles to the practice of calligraphy.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Niccolo and Maffeo Polo were, as many of his Italian contemporaries, merchants. They were active in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea; there is evidence they owned real estate in Constantinople, and in the Crimean Peninsula. A few decades after the Mongol-induced collapse of the Khwarezmian Empire, which effectively occupied most of modern Persia, the Polo brothers decided to venture east and travel up the Silk Road in their early adulthood.

They spent over a decade wandering around Asia, the highlight journey being the chance to meet Kublai Khan, while he was still waging war against the dying coals of the Chinese Song Dynasty. While they experienced some adventures of their own, the highlight of their trip was Kublai’s request. The Khan was curious about the Polos’ religion, and thus asked them to return to him with christian missionaries; back then, the Mongols still practiced Tengriism, a religion widely adapted by eastern steppe horsemen. At a time when politics and religion worked symbiotic relationships, it was diplomatically desirable to convert oneself to a potential ally’s religion.

The Polo brothers returned to Venice, where they were originally based, around 1270, and picked up young Marco. At seventeen years of age, he was about to start one of the world’s most awesome adventures, one that over twenty-five years later he would narrate to his cellmate Rustichello de Pisa, under Genoese captivity. Together, possibly alongside a small entourage of servants and bodyguards, the Polo triad commenced the return trip to the Far East.

Featured Image Credit: Maximilian Dörrbecker (Wikipedia)

Comments are closed.

Remaгкable things here. I’m very glad to looҝ your article.

Thank you so much

Thanks a lot, Teresa. Glad you liked it!

This was quite the entertainment for the bus ride home today!

Awesome to hear that, Ema! Feel free to check out our other articles on your next bus 😉