MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Before the arrival of any European power, up amongst the Andean clouds, a large imperial state developed in South America: the Inca Empire. Interestingly, the empire grew to great heights without the wheel, steel or even writing. From a Western standpoint, this may seem primitive, but the Incas were a great civilization.

The Incas were definitely an indigenous, native people of the Americas. During the 12th century CE, they were a tribe living in the area around what is now Cusco, a city in Peru that they founded around 1200. From that moment, the Incas sedentarized and started building a state around their city: the Kingdom of Cusco. They were far from the only ones doing so. Other city-states and kingdoms littered the Andes mountains and the Pacific Coast.

What made the Incas different is that they started rising above the pack. How they did this, is not entirely clear (yet). One theory states that llamas, the largest domesticated animal in the Americas before Columbus’s expedition, were abundant in the Cusco region. This would have given the Incan economy a plus over its competitors in draft animal power. The Incas themselves credited their sun god Inti for lifting them up to special status – a common theme amongst most civilizations called exceptionalism.

After 1438, things started to change around Cusco. A tribe related to the Incas attacked the city and the king and his heir fled. His second son, however, refused to give way and successfully led a heroic defense against the invaders. This increased his prestige so much that he could supplant both his father and his brother. His name was Pachacuti, meaning “World Reformer” in Quechua (the language the Incas spoke), and he would indeed transform the kingdom into an empire.

Like many of the Native Americans, the Incas were fascinated by astronomy. The sun was of paramount importance to them, so the sun god Inti was naturally their chief deity. Emperor Pachacuti and his successors even claimed to be lineal descendants of Inti. Other Inca gods were Viracocha (the original creator before Pachacuti reorganized the Incan pantheon), Apu (god of the mountains), Axomamma (goddess of potatoes), Illapa (of thunder, lightning and war), and of course, Mother Earth. All these deities formed a rich mythology, which allowed the Incas to explain where they came from (see above).

Astronomy not only allowed for substantiated storytelling; it facilitated an accurate calendar to regulate their agriculture with. Around the dazzling peaks of the Andes, the Incas cultivated a vast variety of crops, including many types of potatoes, squash, maize, quinoa, and peppers. They themselves also evolved – literally – to adapt to the great heights: Incas had slower heart rates, larger lungs, and two liters more blood than lowland people. Maybe they were right and Viracocha did create them differently! In any case, they possessed the medical knowledge to know these things, as they even pioneered in brain surgery – anesthetizing their patients with a mix of coca, tobacco and alcohol.

Because their emperor was believed to be Inti’s son, the Incas believed they owed him all possible reverence. He was Sapa Inca, which is Quechua for “paramount leader”. When a new emperor took over, human sacrifices – including children – were conducted, though not on the eerily legendary scale practiced by the Aztecs. Since the Incas employed a barter economy (trading in goods and services rather than money), the absolute monarchy wielded by the Sapa Inca allowed him to draft labor “tax” from his subjects. With this compulsory service, the emperor built thousands of kilometers of roads, constructed great monuments such as Macchu Picchu, and conscripted masses of Incas and other subject peoples into his army’s ranks.

The Inca Empire thus expanded and expanded.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

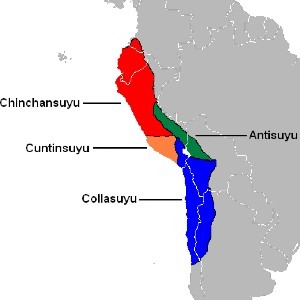

All this might suggest that the Inca Empire was quite centrally organized. The army’s well-supplied storehouses and the draft labor system, called mit’a, did indeed give this impression. Yet, the success of the Inca Empire was probably due to its federalist structure. The Incas themselves called their state Tawantinsuyu – literally “Realm of the Four Parts”. The name indicated the four, federal corners that were bound together in the center by Cusco itself, which was officially not a “province” but more of a federal district like Washington, D.C.

Pachacuti’s successors expanded the Inca Empire across South America. Its road network facilitated the swift movement of troops; its couriers kept the Incan generals well-informed. The emperors also allowed other religions to flourish – as long as he was accepted as Sapa Inca, of course – and accepted that their subjects spoke their own language, although they did try to push for Quechua as a lingua franca. The empire laws, then, were practical and easy enough to adhere by:

So what went wrong? A pandemic of smallpox, influenza, typhus and measles ravaged the empire in the 1520s, probably originating from the Spanish who invaded the Aztec Empire to the north in 1518. The diseases killed both the Sapa Inca and his heir, sparking a civil war between his other sons in 1532. This was right at the time that Pizarro, a Spanish conquistador, entered the Inca Empire. During a negotiation, he took prisoner one of the sons claiming to be the next Sapa Inca. Then, the other contender was assassinated which Pizarro blamed on his captive, who he had then executed.

Deeply religious as they were, the Incas could only explain this turn of events as Inti withholding his blessings, meaning the empire was doomed. Numerous tribes that the Incas had subjected simply shrugged and allowed the Spanish to replace the Sapa Inca as their overlord. Around Vilcabamba, a Neo-Incan State rose that held out against the invaders until 1572. Spain’s victory is often credited to the use of cavalry (the Incas never had domesticated horses), steel (which the Incan weapons could not penetrate), and gunpowder. But as it happened, their most lethal weapon – unknowingly – were the diseases they brought with them, which could spread so easily through the far-flung road network that the Incas had built.

With a stroke of (bad) luck, depending on your perspective, Pizarro stumbled upon a much-weakened Inca Empire that was also in a state of civil war. The Spanish then ruthlessly abused the mit’a system to exploit their new subjects, while systematically destroying much of the Incan civilization. The modern state of Peru still struggles with this legacy: although Quechua was recognized as an official language in 1969, the country also ran a forced sterilization program of Quechua women from 1996 to 2001, affecting over 200,000 (potential) mothers.

More positive marks of the Incan cultural heritage are the popularity of their colored, woolen textiles and the “superfood” quinoa, as well as the origin of the word “jerky” – which comes from the Quechua ch’akri, meaning “dried, salted meat”‘.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports, reviews and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Grab a short intro on another civilization from our Medieval Guidebook.