MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

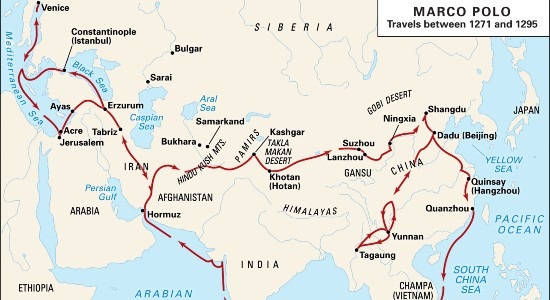

Allegedly, Marco Polo traveled to places that his fellow Europeans could have only dreamt of. In his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, he claims to have followed the entire Silk Road, all the way from Italy to China. If his account is to be believed, Polo crossed both the endless deserts and the towering mountain ranges of Central Asia to get there.

Once arrived, The Travels tell us he supposedly served at the court of Kublai Khan for years, even serving as the khan’s diplomatic emissary to India, Vietnam and Indonesia. Then, in 1295 CE, he returned from the Far East to his home in Venice, laden with gemstones.

That must have been proof of a successful trip to the edge of the medieval world. Right?

The itinerary described in The Travels, with facts regarding places and cities, is verified easily enough. But Polo also makes bizarre claims about sorcerers and unicorns. This, however, had largely to do with his unfamiliarity with the many Asian plants and animals he encountered – such as rhinoceros, his “unicorns”. These outlandish assertions, on closer inspection, may serve as proof that he did visit lands that must have been nothing short of mystical to his 13th-century eyes.

When Marco Polo put his adventures to paper via The Travels, the book turned into an instant classic. Ever since, claims about his crazy adventures have run amok. His adventures even inspired Netflix to create a TV series named after him in 2014, with a cast of Lorenzo Richelmy as the wayward traveler himself and Benedict Wong playing Kublai Khan. (Alas, the third season of Marco Polo has been canceled because Netflix reportedly lost US$ 200 million on the project.)

According to historians, the series mixes facts with fantasy – true in spirit, one might say, to the historical Marco Polo.

Over the centuries, modern readers have inflated the adventures from The Travels even further; myths about Marco Polo that often circulate nowadays include:

On the other hand, critical readers of Marco Polo’s story often bring up questions like:

These questions have easy, historical explanations that acquit the Italian traveler from accusations of making it all up. But the more serious questions surrounding The Travels remain. That’s why this article is going to explain who Marco Polo was and whether his tall tale is true.

In short, we’ll be answering the question: did Marco Polo actually visit China?

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

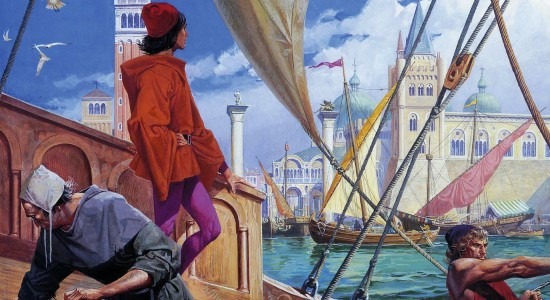

Born in Italy in 1254 CE, Marco Polo was a Venetian merchant who left his home city for the Far East when he was only 17 years old. He did not see himself as an explorer, but preferred the term “wayfarer”. His final destination was China, and for good reason.

China, at the time, was the eastern end of the legendary Silk Road. The country was fabulously prosperous and industrious, or at least it appeared so to observers coming from the west. By the time Marco departed from Venice, most of the country had been conquered and unified by the Mongols. This was quite the accomplishment as China had been divided for more than three centuries by then. (In fact, Marco Polo called China “Cathay”, after the Khitan dynasty which had ruled Northern China for over 200 years.)

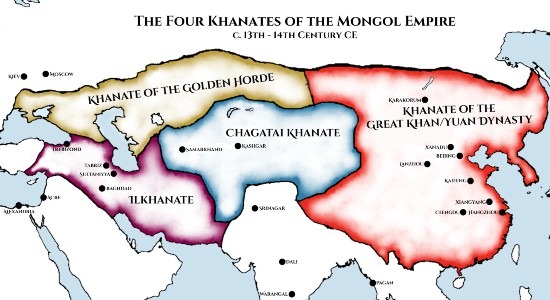

The Mongols fanned out in every direction, invading Central Asia, Vietnam, Persia and attacking both the Rus’ and Mameluke Egypt. They thus created the largest land empire the world had ever seen. After the terror – which they often brought with them – fizzled out, the unification of so much of Asia under a single ruler revitalized the languishing Silk Road. The wealth of China once again attracted European travelers to the East. So, too, did Marco Polo’s father – Niccolò Polo – set off around the year 1260 to meet the Mongol khan.

Niccolò and his brother met him at Dadu or Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing) roughly six years later after several deviations. (This alone makes Marco definitely not the first European to visit China.) The Mongol ruler at the time was Kublai Khan, a grandson of the great conqueror Genghis Khan. He received Niccolò Polo and his brother warmly but made a very specific request as well. Kublai Khan asked the Polos to return to Europe posthaste to deliver a letter to the pope. In it, Kublai requested the Holy Father to send 100 educated men to the East, so they could teach Western customs and Christianity to the Mongols.

Niccolò Polo returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270, where he met his son Marco – now 15 or 16 years old. For various reasons, the pope took a long time to respond to the khan’s request. Hungry for continued commerce and adventure in Asia, Niccolò stopped waiting and sailed from Venice the same year. Young Marco Polo, now around 17 years old, was with him. If the stories are to be believed, it would take 24 adventurous years before he returned to Italy.

Marco Polo did not write The Travels while he was on the road; in fact, pen found paper only after he was back in Italy. He had made a fortune in the East but found his city in the midst of war when he returned. Venice was fighting with one of its competitors, the Republic of Genoa. Now an affluent man, Marco Polo decided to sponsor his city’s war effort and hired, manned and armed a galley. Not much of a strategist, however, Marco was soon taken prisoner at sea by the Genoese.

He spent the next years in captivity. Always a great storyteller, Marco Polo entertained his fellow prisoners with accounts of his adventures. His cellmate, one Rustichello de Pisa, penned most of them down and thus wrote The Travels of Marco Polo. This is where the first problems of veracity pop up: Rustichello was a romantic writer and probably embellished Marco Polo’s account. A modern English translator of the work has argued that its more fantastical elements were probably by Rustichello’s hands, going so far as drawing from Arthurian legends.

The name of the book also draws attention. It was originally published in Franco-Venetian as Livre des Merveilles du Monde (“Book of the Marvels of the World”) or simply Devisement du Monde (“Description of the World”). The Italian or Tuscan versions of the book, however, were released under the name Il libro di Marco Polo detto il Milione (“The book of Marco Polo, nicknamed Milione”).

Debate is still ongoing about the term Milione. Some have postulated that it refers to his affectionate nickname (E)milione. But according to a 15th-century humanist, the Venetians called him Messer Marco Milioni (“Mr. Marco Million), because he kept droning on about the millions and millions that Kublai Khan supposedly possessed. More recently, contemporary scientists stated that Italians started calling Marco’s book Il Milione on account of its “million lies”. The book’s title alone is enough to spark incredulity and scientific debate.

As Europeans established steadier contact with East Asia in the 16th and 17th centuries, questions about Marco Polo’s adventure began to arise, from cultural observations of the peoples he described to geographical matters. Many scholars went as far as dismissing the tale altogether, claiming that Polo probably only visited Acre, and perhaps at most, the western Caucasus – the rest being second-hand testimonies and outright falsehoods.

These are valid claims, when in context. Marco Polo’s narrative is inconsistent when acknowledging distances, measuring them in days, but rarely specifying whether that is walking or riding an animal, less so the distance covered any given day. Directions are spotty, although – in the merchant’s defense – a lot of the regions he traveled through were inhospitable deserts or seemingly endless plateaus.

He describes these vast desolaces by detailing how in some quite particular regions there are no sources of drinking water, but ample salt-lakes or potentially noxious springs. This meticulous detail of existing places in the Central Asian deserts serves as evidence of Polo’s visit to the area – or at the very least, that he came close enough to them.

Then, there are the names. The term Saracen had been in use in Europe for some time to refer to muslims essentially everywhere save for Spain, which came to include peoples of many nationalities and ethnicities – Arabs being only one of those peoples. Polo does make use of the container term, and it makes sense; many of the peoples he likely encountered were unknown to all but a few Europeans.

Cities throughout Asia also fall under the naming problem, sometimes cryptically spelled. Mosul is called Mausul, Baghdad is Baudas, and Kabul is Caobul. Furthermore, Polo constantly refers to regions and areas as kingdoms and princedoms, which while inadequate, might have been used to facilitate understanding of the text; after all, the book is directed to a European audience, about places and tales that Polo experienced in vastly different languages.

The first few chapters of The Travels of Marco Polo refer to his father and uncle’s travels. It’s only in Chapter X that Marco’s own tale commences, in what amounts to a side-note on his travel from Venice to Acre in the Holy Land. There is no description of Acre itself, as it was a city within the sphere of direct European contact. While in town, they met with the newly elected Pope Gregory X, who entrusted them with letters to the khan and sent two friars with them to dispense all kinds of ordinations and absolutions – a tad bit shy of the 100 men that Kublai Khan had requested.

Among the peoples specifically named by Marco Polo in this part are the Kurds, Cumans, and Georgians. Of the Kurds, Polo says that they live in a region where muslin and expensive fabrics and carpets are produced. Regarding the Cumans, he mentions that they predated Mongolian presence in the steppes north of the Caucasus (although, as usual, referring to the Mongols as Tartars).

On the Georgians, he particularly mentions the name of their king, David, and that they are “christians of the Greek rite”, by which he means Orthodox. He goes deeper, explaining part of the ancient history of the Caucasus region, going back as far as Alexander the Great’s attempt to conquer it, and saying that their people are “handsome, capital archers, and most valiant soldiers.”

In the following chapters, he seldom mentions whether he visited any given place himself, or whether he heard of it from someone else. However, descriptions of the regions and customs of the peoples support that he may have been to the places he speaks of. Though he opens the travels describing the two Armenias, as he calls them, the journey starts in Turcomania, which corresponds to modern-day Anatolia.

It is noteworthy that he mentions that its inhabitants, which can be assumed to be Turks, apparently speak “an uncouth language of their own”. This testimony favors the notion that Polo did not, as some scholars have proposed, speak Turkish dialects – the merchant says that he spoke, in addition to his native, four languages. These may have been a few variants of Persian and Mongolian, different enough from each other to count as different languages. Polo most likely did not speak Chinese, as the language of Kublai Khan’s court was most definitely Mongolian.

His descriptions of Turcomania, the horses bred there, the fabrics woven, the adjacent regions (including “Casaria”, a then anachronistic term for Khazaria; by Polo’s time, the Khazars had largely been absorbed by other Turkic tribes) and its Greek and Armenian minorities are far too accurate and convincing, to truly believe he never went to these regions. At the time, Turcomania was under the control of the Ilkhanate, the southwestern division of the Mongol Empire. As the journey progresses east, Polo accurately notes to which of the four Khans towns or provinces were subject.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Polo’s journey continues to Persia, where he remarks on the quality of the horses and, interestingly, states that they cost a sum comparable to 200 livres tournois in the local currency. Of donkeys, he states that they could fetch 30 marks of silver. This again supports that Marco may have visited the area, as for him to make this conversion he had to have a strong understanding of the local currency in Persia, and the exchange rates going with it. Further, he names the 8 different subdivisions of Persia, and praises the Ilkhanate’s government for establishing a law-and-order regime, explaining that – prior to the Mongol conquest – deadly bandits proliferated in the area.

In Persia, he notes, everyone is a Saracen, and a great many fruits and crops are grown, alongside cotton. Marco tells that in Persia wine is produced, and quickly anticipates that the European reader will be surprised by the fact, because “the Saracens don’t drink wine, which is prohibited by their law”, then pointing out that the wine is boiled and thereafter drunk as a sweet beverage. Again, strong evidence that the Venetian did indeed spend time in Persia, and proof that Europeans were well acquainted with the muslim world and Islamic doctrine.

If there is one place that Marco Polo almost undoubtedly visited, it’s the port city of Hormuz, on the shores of the Persian Gulf. Polo goes into tremendous detail about the journey from northern Persia to the city of Hormuz, and thoroughly elaborates on the city itself. He names the “king” (likely a governor), describing the weather in particular affinity, the ships of the Indian merchants arriving at the docks, the many commodities traded, the healthy diets of its inhabitants, the peoples’ looks and religions, and the terrible storms that run throughout the Indian Ocean, making the trip by sea a particularly fearsome enterprise – a route that Polo himself is supposed to have taken on his journey back home.

After describing Hormuz, Polo tells the reader that he will tell of “the countries towards the north (…) in regular order”; essentially, from west to east.

A constant in this section of the book is the abundance of deserts. Around Cobinan and Tonocain, a city and a province, respectively, there are deserts so barren that water and food must be carried for the cattle. Brief descriptions of both imply that Polo may have spent a few days there at most, as will be the case with many other places towards Tartaria (Mongolia).

It is unclear what animals he and his entourage traveled with, although it is almost certain that the Polos would have used camels, these being the most ubiquitous and reliable beasts of burden for extended journeys through the desert. When going towards the city of Sapurgan, Polo exceptionally mentions that “sometimes also you meet with a tract of desert extending for 50 or 60 miles”, atypical to his way of defining distances in days. This vagueness makes the Silk Road seem stranger, and more distant and mythical than it was perceived even before Polo’s journey.

Upon reaching a certain city named Balc, in the north of modern Afghanistan, he speaks of the marble ruins of palaces and temples, a product of waves upon waves of war and destruction, and that its inhabitants preserve the tale of it being the city where Alexander married the daughter of the Persian king Darius. Polo also marks this as the border between the Ilkhanate (or the domains of the Tartar Lord of the Levant, as he calls him), and the Chagatai Khanate.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Further east, Polo ventures into the mountains of Central Asia. In the province of Badashan, he notes, everyone is of the muslim faith, and its hereditary kings claim Darius as their ancestor. Throughout this part of The Travels, Polo wanders on and off about the wonders he sees in one province and hears of others. In Tangut, he observes idolaters who curiously burn their bodies; in Keshimur (Kashmir), he observes sorcerers who can darken the skies and weather. Elsewhere, Polo claims pyromancers and conjurers of cheap tricks abound. Wandering these desertic plateaus, the Venetian speaks of how the region is involved in the production and trade of rubies and lapis lazuli, the latter still being plenty in Afghanistan today.

While in Central Asia, Polo breaks from his usual narrative and speaks in first person to tell of an acquaintance of his who had devised a fabric allegedly made of salamanders, one so wonderful that could get bleached when put to fire. There are a few options here at play, and arguably all equally likely. The material may have been asbestos, or Polo was exaggerating, or it was indeed some sort of unique fire-proof fabric lost to time. After all, ancient and medieval secrets, such as the recipe for Greek fire, were so precious that they were ultimately forgotten as a result of their secrecy.

Although the Book of Marvels is generally written in a linear way, Polo’s somewhat incoherent narration makes it possible that some of the places he describes or mentions on his way eastward, he might have visited or heard of well after meeting the Khan for the first time, an encounter that seems to have transformed him.

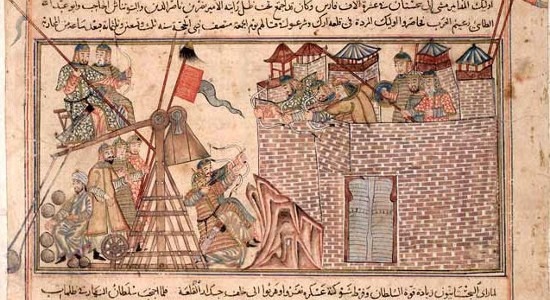

Polo arrived in China in the middle of the 1270s, as the conquest of the country by the Mongols was finishing up; bits and pieces mostly to the southeast of the country were the previous Song Dynasty’s last remnants. Polo narrates the conquest of China, most likely from what he heard of the other members of the Khan’s court, emphasizing certain battles and setbacks suffered by the Tartars, as he kept calling the Mongols.

When Marco Polo finally starts describing Kublai Khan and his court, he does well in telling the reader that Khan means “the Great Lord of Lords”; in practice, no single word in most Indo-European languages makes justice to this title, yet Polo showers the Mongolian ruler in praise of his greatness. In a chapter already into the Mongolian part of his story, he describes the Khan as having a white face, with fine eyes, being of “middle height” and perhaps corpulent – his language is ambiguous, perhaps suggesting he was overweight without dishonoring his once lord. He tells of his four wives and his legitimate sons, adding that the entourage of each member of the royal family numbers in the hundreds of people. Polo further states that the Khan’s wives and concubines were sometimes called upon to serve him as diplomatic or administrative envoys.

As any other European would back then, Marco marveled at the Khan’s palace in the winter capital of Khanbaliq (nowadays called Beijing), the capital of Mongol China. The palace in question was a whitewashed square of over six kilometers in perimeter. Each corner and half-length of the palace’s walls housed what Polo calls a palace; they may have been keeps, much in the European fashion, where garrison guards lived. Allegedly, pieces of the Khan’s own armor were scattered throughout those keeps.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

In the courtyard, there was a one-story hall “so large that it could easily dine 6000 people”, its walls covered in vibrant red, green, and blue lacquers. The hall was adorned with carpentry; gold and silver cups and plates were everywhere to be seen. Gardens, as well as a menagerie and artificial lake stocked with fish, were kept in the enclosure.

Supposedly, when Kublai Khan saw trees of his liking, he had them uprooted and carried back to his palace on the backs of elephants, which may very well be true; after all, the Mongol Empire had lucrative commercial connections with southeastern Asia, where elephants were prized beasts of war and burden since ancient times.

War being as essential to Mongolian existence as horsemanship itself, Polo describes the meritocratic system of the Mongolian military, mentioning that officers who distinguished themselves in battle were promoted to command units ten times the size of their original ones – already in the early 13th century, the Mongols were using the decimal system to organize their armies.

The Keshican, which Marco translates as “knights devoted to their lord”, constituted the household guard. 12,000 strong, these heavily armored horsemen worked in shifts of three days and nights of 3,000 men each. Etymologists and historians have concluded that the name seems to derive from the name of a Mongol tribe that dwelled north of Beijing, the Keshikten.

The city of Khanbaliq, outside the palace walls, gets a share of text as well – accurate enough to corroborate Marco’s presence. Enclosed by a square of forty kilometers worth of thick walls, the city is described as having plenty of houses and plazas, and streets so perfectly straightened that one can see from one wall to the other through them. But the description is relatively bland and short when compared to the Khan’s palace.

Speaking of the Beijing palace, it is often brought up that if Marco Polo really went to the Far East for years on end, how come he fails to mention either the Forbidden City or the Great Wall of China? Another astute observation that critical readers of The Travels put forward is that neither eating with chopsticks nor foot binding are mentioned in the book. Surely these customs and the mentioned landmark buildings must have left an impression on a 13th-century Venetian?

To study these allegations, we must take a close look at the China that Marco Polo visited. The country had just come under the rule of the Mongols, a martial steppe people that looked down on many traditions held by the ethnically Han Chinese. Foot binding – a gruesome practice, fortunately now extinct – was done to make a woman’s poise “more gracious”. It was a status symbol of feminine beauty in an urbanized and stratified China. The Mongols, on the other hand, were generally way more interested in martiality, ferocity and virility – a woman in Mongol society did not need crippled feet in order to look attractive.

As for the Great Wall, the size, shape and scope it’s currently remembered for is a form that it took largely under the Ming Dynasty, which succeeded the Mongols in the 14th century. Parts of the fortifications were built earlier, but we should remember that those were meant to keep out steppe nomads – like the Mongols! Now that these nomads controlled both sides of the Wall (China and Mongolia), the defensive line probably played no role of significance in the decision-making of Kublai Khan’s court. The Great Wall was obsolete.

The Forbidden City, too, was largely constructed under the Ming emperors. Marco Polo could not have described the complex, or the Great Wall as we know it, for the simple reason that they were later constructions. In fact, the Beijing palace of Kublai Khan was long lost. Only as recently as 2016, archeologists may have found its remains underneath the Forbidden City.

Concerning the chopsticks, we’ll talk about food later.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Continuing Marco’s narrative from the points where he met the Khan, he introduces the “Tablets of Authority”. These instruments were crucial in stressing how much security had improved under Mongol rule in most of Asia. Polo describes how military officers were given these ornate tablets of silver or gold, according to their rank. On it, an inscription reads “By the strength of the Great God, and of the great grace He hath accorded to our Emperor, may the name of the Kaan (sic) be blessed; and let all such as will not obey him be slain and be destroyed”.

Essentially, Mongol rule was so strong that, under the Khan’s jurisdiction, a man could carry an inscribed tablet worth a small fortune just to validate him as a royal emissary. It guaranteed him assistance and supplies, as well as direct protection by the Khan – which is exactly what happened to Messer Polo.

In the seventeen years Marco is said to have spent in China, he mostly acted as an ambassador or envoy for Kublai Khan. While most of his tales could come across as true, given the independently verifiable evidence, his own claim of being a provincial governor for three years casts a shadow of doubt over all of them. To his favor, though, he might have just tried to convey some sort of office or administrative occupation to which medieval Europeans simply had no equivalent.

It seems that Polo traveled to much of eastern China and the northern bits of Indochina. He drops the names of cities and towns, loosely describing them and their peoples, and spelling their names in ways that are often puzzling to historians and linguists alike. As usual, he is generally content with saying what places sell what at the best prices – the man was Niccolò Polo’s son after all. But it seems that, at the time, silk and spices across all of China were as common as bread and beer would have been in Europe.

A particular group of “idolaters” who Marco Polo kept finding throughout Central Asia and southern China, he remarks, holds all life sacred, and go far out of their way to avoid harming insects, even when erecting buildings or working the fields. Their peculiar way of worship and their temples are consistent enough that, when cross-referencing a religious map of eastern Asia, one can safely guess he is describing buddhists, one of the few pre-modern descriptions of the faith by a European.

Apart from Khanbaliq, one of the cities in Cathay that really caught his attention was Kinsay (modern-day Hangzhou.) Kinsay, Marco says, has 12,000 bridges looming over its many canals. This is as likely an exaggeration as is his claim that the Khan employed 10,000 falconers. (See where the name Il Milione comes from?)

Polo estimated that the city may have held well over 300,000 people – though an astonishing number, this is likely. During the Middle Ages, China might have been home to as much as a fourth of the world’s populace, and in peacetime, under the Tang and Song dynasties, its biggest cities made any christian city in Europe look like a village.

People in Kinsay, he observed, used paper money. His European audience at the time was familiar with the concept, but Europeans didn’t embrace paper as currency until a few centuries later. Overall, his description of Kinsay is so lengthy and thorough, that it’s reasonable to believe he spent considerable time there.

Marco also heard stories while in Kinsay, about a mystical island far across the sea called Cipango. We now know this place as Japan.

The people Polo met told him that on the island of Cipango there was a mythical city made fully of gold. The material was apparently so abundant that it literally served to pave the streets and floors. Polo’s mention of Japan seems to be the first time a European ever heard of the country.

He further explains how the Mongols attempted to invade it twice and how they were twice foiled by terrible storms, an incident that the Japanese attributed to the “Divine Wind” – or in Japanese, kamikaze.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

After nearly two decades of serving the Khan, Polo understandably felt homesick. So he asked the Khan permission to return; he may have done so a few times earlier, but the Khan seems to have enjoyed Polo’s company and appreciated his service far too much. Thusly, he imposed on him and his entourage one last task.

The Polo triad (Marco, his father and his uncle) was to escort Kököchin, a Mongol princess, to marry Arghun Khan, khan of the Ilkhanate. At the time, various khanates were warring against each other, so the land route was out of the way. The Polos were to sail through the straits of Malacca and on to Persia.

Marco acknowledges the difficulties of seafaring in the Indian Ocean, saying that it can take up to two years to sail from China to western Asia. This anecdote may have been compounded by the fact that he had to wait for five months for monsoon winds to shift to the island of Sumatra, where he claims man-fish hybrids lived, alongside with unicorns that were the size of elephants – he meant, rhinoceros – and eagles that could carry elephants on their talons.

On their journey back to the port of Hormuz, the fellowship moored on the coasts of the Indian Ocean, both on the Indian mainland and the islands of modern-day Sri Lanka, which he called Ceylon, where Polo describes that many nudists lived. But upon arriving, indeed nearly two years after their departure, Polo received bittersweet news; Kublai Khan had since died. The Khan had been a noble and generous friend to Marco, his father and his uncle, but now the news released them from their obligations.

So they carried on and returned to Venice, arriving in 1295, ending a wondrous journey. They came back loaded with silks, gold, silver, gemstones, and all manners of precious goods, to find most of their family and friends having presumed them dead, and with good reason. The last chapters of the book are spent summarizing the war waged by the many khans over Asia, something which is often overlooked but comes to reaffirm how steady and firm Polo’s contact with the Mongols was.

While there’s a feeling of incredulity surrounding The Travels, which all these past centuries have not managed to take away, there are also readers who inflate the Marco myth even further. It’s often claimed that Marco Polo was the first European to visit China, which we have refuted. He’s also frequently credited with writing The Travels himself – also incorrect.

But an even crazier claim that’s routinely regurgitated is that Marco Polo introduced pasta to the Italians upon his return. This legend was popularized by the 1938 film The Adventures of Marco Polo, which contains a scene of the returning wayfarer introducing his fellow Venetians to spaghetti. In reality, however, pasta was already in use in ancient Italy – centuries before Marco Polo was born. Historians have debunked the myth so many times that we’re virtually certain that Marco Polo did not, in fact, introduce pasta to Europe. Even the International Pasta Organization is with us on this one.

The food war continues, however. There are now even Italians who retaliate with the statement that Marco Polo instead introduced chopsticks to China. It makes for a good story, but it’s beyond doubt that chopsticks were already used by the Chinese since Antiquity.

Why then, as the critical readership of The Travels brings up, does Marco Polo fail to mention these utensils? The answer, again, lies in the Mongol culture of Kublai Khan’s court. At the time, the ethnically Han Chinese probably used chopsticks, but the people at the khan’s court carved with personal pocket knives – as was customary on the steppes of Mongolia.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Evidently, Polo’s legacy has been controversial at best. Parts of his account are without a doubt romantic exaggerations. Yet, we shouldn’t forget that this story was dictated by a 13th/14th-century Venetian to a fellow Italian inmate. With nothing better to do, there was a thorough need for entertainment here. Tellingly, Marco Polo’s last words supposedly were “I have not even told half of what I saw”.

So what to make of all this? We think the above is an abundant warning for taking The Travels of Marco Polo at face value, but overall the book contains way too many details to be ignored altogether: like most historians, we think it’s true that Marco Polo existed and traveled all the way from Venice to China, across the Mongol Empire. It’s probably also true that spent several years and that Marco Polo met Kublai Khan himself. What he did at the khan’s court is a bit hazier; details regarding this part should be read critically – like any other medieval source.

Marco Polo’s contemporaries and early readers during the Late Middle Ages were overly critical. His claims concerning Cipango (Japan) were being disputed. His reputation improved a bit in the 15th century when cartographers took his notes on distances to faith. One such reputed scholar, Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, produced a map that found its way to the hands of a certain Genoese sailor, who tried his best to sell the idea of a city of gold to many monarchs in Europe. However, in 1492, the pleas of this relentless sailor yielded results with Isabella of Castille and Ferdinand II of Aragón.

Probably startled by Portugal’s astronomical progress in establishing contact with the Far East earlier in the 15th century, the Spanish monarchs gave this Christopher Columbus three caravels and a bunch of rowdy sailors to try his luck. While the European colonization of the Americas is thus the most tangible albeit awkward consequence of Polo’s travels, they have permeated popular culture through and through. The book series A Song of Ice and Fire, for instance, places the pseudo-legendary kingdom of Yi-Ti far into the east; what characters in the saga know of the land is whatever tales they read or hear from others, its descriptions loosely approximating a notion of medieval China. On the other hand, Bilbo Baggins’ journey in The Hobbit is somewhat reminiscent of Marco Polo’s; an intrepid hobbit leaves hearth and home to travel to the edge of the known world, and when the protagonist returns – richer than all his friends – everyone thought him dead.

There is something, it seems, that charms the mind and spirit about the romanticized unknown. Centuries after Polo’s time, when humans acquired the ability to journey around the world in a few hours, our gazes finally lifted up from the horizon to focus on the sky; whatever may come next, only the future knows.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports, reviews and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Comments are closed.

I amazed with the analysis you made. Wonderful!

Thanks for your amazing feedback, Jung!

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it is truly informative. I will be grateful if you continue this in future. Many people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Thanks so much, Eduardo! We will continue this; don’t you worry. 😉

I want to to thank you for this great read!! I certainly loved every little bit of it. I have got you book marked to check out new things you post…

Glad to hear it, Pasquale. Thanks for bookmarking us. Come again soon!

Great topic. I must spend a while learning much more. Thanks for magnificent information I used to be looking for this information.

Thanks, Marisol. Glad to hear we were able to provide what you were looking for!