MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Vietnam has seen its fair share of invasions, both in modern and medieval times. Usually it were the Chinese who meddled in Vietnamese affairs, with varying results. In the 20th century, one of the world’s superpowers, the United States, tried the same and failed spectacularly.

How did the Vietnamese fare against the near-global superpower of the 13th century CE, the Mongol Empire? During the later Middle Ages, the Mongols gained a reputation as inexorable conquerors. But was this aura of invincibility justified with regard to their campaigns into Vietnam?

It turns out that – not unlike the modern Americans – the great medieval Mongol Empire struggled to subdue the Vietnamese.

Grab a short intro to medieval Vietnam from our Medieval Guidebook.

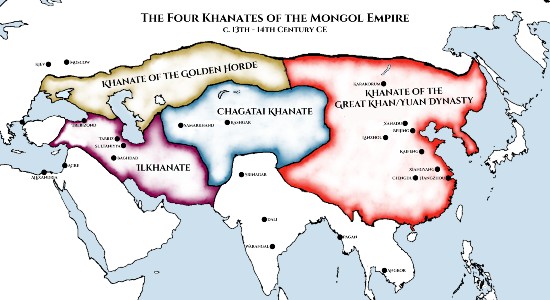

Under the leadership of Genghis Khan and his offspring, the Mongols conquered most of the medieval world, expanding their empire from Korea in the east to Syria and Ukraine in the west. After the death of Genghis’s son, this realm splintered into various parts. Genghis’s grandson, Kublai Khan, set himself up in China and fulfilled the long-cherished wish of the Mongols to completely conquer the country.

Kublai had himself crowned emperor in 1271 CE and – whilst formally deposing the previous dynasty – founded the Yuan Dynasty. His Mongol family line would rule the native Chinese for nearly a century.

No longer a tribal leader, Kublai felt he had to incorporate a couple of China’s age-old imperial policies, such as its conduct regarding neighboring countries like Korea, Thailand and Vietnam. The dynasties before Kublai Khan had always attempted to subdue these civilizations by imposing tribute on them.

Vietnam in particular had time and time again been forced to pay significant sums to the Chinese emperors. Before long, emperor Kublai, too, started demanding submission from the two Vietnamese kingdoms that existed at the time.

Both monarchs had been on relatively good terms with the previous Chinese dynasty and didn’t like the new Mongol usurper one bit. Unsurprisingly, they were not really forthcoming in heeding Kublai’s demands. They paid a modest sum to the Yuan court, but the Mongols were far from satisfied.

Immediately, Kublai prepared a punitive expedition, aiming to strike deep into Vietnam to teach his insolent “subjects” a lesson. However, the emperor had just lost many men and even more war supplies in his disastrous invasion of Japan. Regardless, he felt he had to impose his authority on the Vietnamese now, lest they grow even more disrespectful in the future.

Kublai sent a force of 5,000 men ahead – a small number by Mongol standards. It was not enough.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

The expeditionary force landed on Vietnamese shores in 1283. Ready to drive their invaders back into the sea, the Vietnamese immediately attacked with a much larger army, apparently over 10,000 strong and with many elephants. The Mongol army, however, boosted by decades of campaign experience all over the world, withstood the initial onslaught and actually managed to defeat the Vietnamese army.

They lacked the numbers to impose their will on the wider region, though. For the next two years, the Mongol Yuan soldiers had to fight tooth and nail to hang on to their bridgehead. The Vietnamese deployed guerilla warfare to demoralize the Mongols and deplete their supplies. Eventually, the Yuan army was down to their last fort on the beach. Its commander wrote to emperor Kublai, asking for reinforcements.

Having recovered from his Japanese fiasco, Kublai Khan now sent his son Toghon and 20,000 men to invade Vietnam from the north. In return, the Vietnamese assembled an even greater army, apparently numbering over 100,000 men. It was to no avail: with their wealth of experience and their excellent organization, the Mongols beat back the Vietnamese and drove them to the south.

The Yuan army took many prisoners. Exemplary of their fanatical hatred of the Mongol invaders, many Vietnamese soldiers had tattooed “Sát Thát” (“Death to the Mongols”) on their arms. It cost them dearly: Mongol army command summarily executed anybody who had decorated his body in this way.

Within a year, Toghon even managed to capture the Vietnamese capital. But there, he received his first taste of Vietnam-style resistance. The city was completely deserted, the palace was empty, and the food stores were depleted.

In the countryside, the Vietnamese plotted revenge.

With hit-and-run tactics, the Vietnamese harried the Mongol soldiers and lured them ever further into the country. Giving chase, the Mongols gradually overextended and split up into smaller groups. These groups were then ambushed by the Vietnamese and killed off. The Yuan army was being slowly whittled down.

On top of that, the summer heat, disease and starvation (for lack of supplies) started to take their toll. Moreover, the Mongol army, with its heavy cavalry units, was ill-equipped for a prolonged conflict in the dense, Vietnamese jungle further to the south.

A daring Vietnamese prince even launched a surprise raid against the Mongol headquarters in north Vietnam. He managed to destroy what little supplies the Yuan army had left. Toghon’s forces then collapsed into disarray and forced their commander to allow them to return to China.

Scared of the poisoned arrows that kept flying at them seemingly out of nowhere whenever they entered the jungle, the Mongol soldiers made special preparations to get their general home safe and sound. Simultaneously genius and humiliating, they made a copper box and transported Toghon north in what must have felt like a sarcophagus already. Whilst they desperately dragged themselves across the Chinese border, the Vietnamese retook possession of their capital and celebrated their defeat of the mighty Mongols.

But Kublai was not done.

Infuriated and incensed, emperor Kublai and Yuan China prepared to strike again. It took the Mongols two years to muster a response on the scale now deemed necessary. Calls were distributed throughout Kublai’s empire to supply troops and materials. The Mongols, of course, made up the bulk of the new army, but native Chinese and Jurchens were levied in great numbers as well. In the end, the total force allegedly numbered over 170,000 (!) men.

By late 1287, Kublai Khan ordered his son Toghon to try again. The great army marched south and crossed into Vietnam. On land, Toghon was initially successful. Before long, he captured the – once again deserted – Vietnamese capital.

But on water, the Mongols made mistakes. They split their fleet into a combat division and a supply division. The combat ships quickly sailed up the Vietnamese rivers to contribute to Toghon’s successes. But the supply ships were much slower and carelessly left behind, vulnerable to attack. The Vietnamese navy spotted an opportunity and attacked the Mongol supply fleet in Ha Long Bay. Many Mongol ships were sunk, and thus a lot of Yuan supplies were lost before the campaign had even started.

Toghon found himself in a by now eerily familiar situation. On account of his initial successes, he had once again penetrated deep into Vietnam but because of the enemy’s guerilla tactics and the loss of part of his fleet, supplies quickly ran low again. He tried to retreat somewhat north, closer to the Chinese border, in order to shorten his supply lines.

The Vietnamese, however, sensed an opportunity to play the same trick twice and sought to repeat the events of the previous invasion. Their sappers went behind enemy lines and destroyed bridges and roads, cutting off Toghon’s retreat to the north. The Mongols were now sitting ducks in the middle of the Vietnamese countryside.

“What the Yuan army needs most of all is food.”

— The Vietnamese king commenting on the Mongol supply situation

Having brought so many men with him, Toghon thought his victory inevitable. As the saying goes, there’s strength in numbers. But when you are deep in enemy territory and undersupplied, a large army – especially one with thousands of horses to feed – becomes cumbersome and unwieldy.

The Vietnamese started laying into the Yuan army once more. As starvation broke out in the Mongol camp, the invaders were again subjected to a bombardment of poisoned arrows. Unwilling to suffer the humiliation of the copper box again, Toghon was out in the open – and thus a prime target.

Before long, the Yuan commander was hit by such an arrow and quickly fell ill because of the poison. Mongol morale completely collapsed. Toghon’s guard managed to sneak him out of the camp and – embarrassingly – had to carry him all the way to China again, avoiding the highways whilst carrying his litter through the dense jungle.

Kublai Khan’s son had failed again. The remains of his army, sufficiently starved and demoralized, were annihilated by the Vietnamese: many Mongols fell or were taken prisoner.

With the land army in shambles, the Yuan combat fleet – which was still in the area – had no further business here. Ships alone could not subdue a country the size of Vietnam, so the Mongol admiral ordered them to sail down the Bach Dang river, back to sea, and – ultimately – towards home. He suspected that the Vietnamese navy would try to ambush him at the river mouth but, with his ships still largely intact, felt confident about running the gauntlet.

Little did he know that the Vietnamese were already sailing up the river, trying to make the most of its small, confined spaces, rather than facing the enemy’s full armada on the open sea.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

The grand prince commanding the Vietnamese fleet was Trần Hưng Đạo. He had studied the tides, and knew the Bach Dang river and its water heights like the back of his hand. Whilst the Mongol land army was being harassed by his fellow countrymen, he had spent days installing pikes and iron-headed poles in the river whenever the tide was out.

During high tide, the waxing water covered the obstacles, allowing the lightest of boats to barely pass over them. At low tide, however, the river was now absolutely impassable for any barge whatsoever. Confident in the effect that his obstacles would have, Trần Hưng Đạo hid his own ships in smaller, tributary rivers nearby and waited for the Yuan warships to come sailing down the Bach Dang.

In the event, the Mongols’ timing was actually quite fortunate. They approached the ambush spot coincidentally at high tide, which would have allowed them to escape. Trying to buy time, Trần Hưng Đạo ordered his ships out of hiding and engaged the Yuan fleet.

The Vietnamese squadrons were not numerous enough to defeat the Mongol navy, but that was not the point. Trần Hưng Đạo was simply playing for time and although he suffered many losses during the initial part of the engagement, he knew exactly at what time he had to retreat in order to use the tide to his advantage.

And so he did, with the heavier Mongol naval force giving chase. The Vietnamese boats barely made it over the obstacles hidden underneath the water, but the Yuan ships crashed with all their weight into the wooden stakes that the retreating water was starting to expose. The trap worked and Vietnamese soldiers from the land army now started to appear on the banks of the Bach Dang, harrying the Mongols with arrows, stones and inflammatory materials.

The battle on and around the river lasted all day but by sunset the Mongol combat navy, just like their land army and supply fleet, had been utterly destroyed.

Emperor Kublai had already been furious over Toghon’s first failure to subjugate the Vietnamese but had granted him a second chance as soon as he possessed the resources to do so. Now, Kublai was beyond himself with rage over the total destruction of Toghon’s forces. He angrily banished his son from the Yuan capital, proclaiming that he never wanted to see him again.

Next, the emperor wanted to plan a new expedition but was persuaded by his councilors to let the idea slide for now. The Yuan court wanted to try and resolve the conflict diplomatically and asked for an exchange of prisoners. The Vietnamese king, wishing to normalize relations with the still mighty Mongols, agreed.

The prisoner who Kublai most dearly wanted back was the admiral of his combat fleet, who had been captured during the Battle of Bach Dang River. The king of the Vietnamese mercifully sent him on his way back home by ship, but prince Trần Hưng Đạo was not done with his opponent just yet. In a daring plot, the Vietnamese admiral arranged for the ship to sink, killing his Mongol colleague.

Upon hearing the news, Kublai Khan fell into a frenzy bordering on madness. He vowed to wipe the Vietnamese from existence and resumed his plans for another invasion. However, before he could follow up on his fateful wish, he was no more.

Genghis Khan’s grandson, the first Yuan emperor of China, died before he had been able to pummel Vietnam into subject status.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

His successor, Temür Khan, wished to straighten out relations with his southern neighbors and immediately offered to negotiate a settlement. The Vietnamese, although jubilant over their successes and the death of Kublai, also sought an end to the conflict. By now, they had managed to defeat the Mongols on numerous subsequent occasions, but the Vietnamese capital had been razed, many Buddhist sites had been destroyed, and the country had suffered great losses in population and property.

Surprisingly, the Vietnamese gave the Yuan court that which had started the entire conflict: they agreed to tributary status. Although the amount to be paid didn’t mean a whole lot and was certainly not as high as the Mongols would have liked, Vietnam assented to become an official albeit rather loose vassal of Yuan China. This situation would continue until the end of the Yuan dynasty.

Because they managed to establish tributary status, historians often treat the Mongol invasions of Vietnam as a success. But militarily speaking, the Vietnamese celebrate their achievements during these invasions and especially their victory on the Bach Dang river as one of their greatest military triumphs. Furthermore, the outcome meant that the Mongols under Temür and his successors never again tried to subdue Southeast Asia.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Featured Image Credit: Loi Nguyen Duc (flickr)