MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Walls are meant to protect civilization. It doesn’t matter whether we think about ancient city walls or large defensive projects such as Hadrian’s Wall in Scotland or the Great Wall of China. We easily conjure images of civilized lands - beacons of progress as they are - that need protection from the ferocious savages of the countryside or beyond.

But this perspective is skewed. In northern Germany, the landscape is littered with the remains of the Danevirke, a medieval fortification system whose name means “works of the Danes”. For a long time, these walls separated the Viking world north of it from the imperial realm to its south. Contrary to popular belief about walls, the “barbarian” Vikings built this barrier; not the “civilized” Empire.

Let’s investigate why this wall was built, whether it succeeded in its mission, and how the Vikings thought about an empire in general.

Grab a short intro to the Vikings from our Medieval Guidebook.

The Danes first appeared in world history during the 6th century CE, at the very start of the Middle Ages. That’s when Byzantine authors started to distinguish between the various North Germanic peoples. They began viewing the Dani, as they called them, as different from the Suetidi, or “Swedes” - although they did notice that both tribes spoke Old Norse.

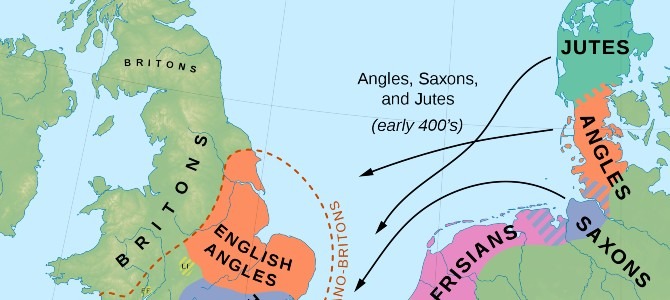

The Dani, or Danes, lived on the islands of Zealand and Funen (still part of modern Denmark) and Scania (the southern tip of modern Sweden). The mainland of what we call Denmark today was the territory of the Jutes and Angles. But, after the fall of Roman Britannia during Late Antiquity, these tribes steadily turned their gaze westward.

A growing number of Jutes and Angles migrated across the North Sea and settled in Britain. This created opportunities for the Danes on Zealand and Funen. They handily took over the mainland of modern Denmark - called Jutland after its original inhabitants, the Jutes.

Moving further south across the neck of land connecting Central Europe and Scandinavia, the Danes then encountered the Saxons. Although a lot of Saxon people had moved to Britain as well (creating - with the Angles, of course - the Anglo-Saxons), enough of them stayed behind to resist the Danish advance. Relations between the (West Germanic) Saxons and (North Germanic!) Danes soon soured.

Because both cultures hardly put anything in writing, if at all, there’s little evidence of all-out Saxon-Danish war at the time. But the archeological record does show that the first version of the Danevirke was built during this period. Evidently, the Danes felt the need to invest time, energy and effort in constructing a wall along the isthmus that gave access to Scandinavia.

The obvious message was: Saxons not welcome.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

The first stage of the Danevirke was a simple rampart made of excavated earth, not unlike a dyke. Around 737 CE, the Danes upgraded the fortification with a timber front and a palisade on top. Thus, they successfully kept the Saxons out of Denmark, but the security situation south of the wall soon deteriorated further.

As it happened, the Saxons came under attack from the west by another enemy. During the 8th century, the powerful Frankish realm encroached on their territory. Frisia, in the modern Netherlands, had already fallen to the Franks in 734; Saxony seemed to be their next victim.

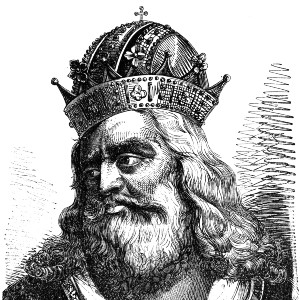

In 772, the mighty Frankish king Charlemagne invaded the Saxons for the first time. It was the beginning of the Saxon Wars, a 33-year (!) period of near-constant warfare, insurrection and rebellion. Even for a commander such as Charlemagne, subjugating Saxony was a daunting task: it took him 18 campaigns.

The Danes felt gravely threatened by these developments. The Saxons had been a threat, but the Danevirke had reliably kept them out of Denmark for nearly three centuries now. Now, over the course of a single generation, Western Europe’s largest state - the Frankish Empire - had replaced the Saxons as Denmark’s southern neighbor.

Even more disturbingly, an explicit objective of Charlemagne’s Saxon Wars was to convert the Saxons to Christianity. This greatly unnerved the Danes, who practiced the Norse religion and worshiped Odin, Thor, Freya, and so forth. On top of that, Charlemagne had himself crowned emperor in 800, signaling his universal ambitions to all Europeans.

In 804, four years into Charlemagne’s reign as Emperor of the Franks, two important events coincided. Old Saxony definitively fell to the Frankish army, ending the Saxon Wars. Simultaneously, Gudfred became king of the Danes.

Realizing the precarious situation to Denmark’s south, Gudfred immediately saw to strengthening the Danevirke. His predecessors had experimented with stonework here and there to improve the wooden palisade, but Gudfred oversaw a comprehensive upgrade of the entire Danevirke. Under his reign, an enormous stone structure came to defend the Danes from the pestering, christianizing Frankish military.

However, Gudfred was not content with defending. In the spirit of the burgeoning Viking Age, he went on the offensive as well. He took the fight to the Franks and invaded Saxony.

The campaign was costly in terms of Danish lives lost. But according to Gudfred, the offensive was a success because the Danes managed to destroy several Slavic trading towns that used to be competitors of Viking commerce in the Baltic. More importantly, by attacking the Franks head-on, Denmark stated that Charlemagne’s imperialism was unwelcome in Scandinavia.

The large Frankish Empire took some time to muster a response, but Charlemagne’s son eventually came to Saxony at the head of a large army. To Gudfred’s disappointment, the Franks undid most of the Danish conquests in the area. But on account of the Danevirke, even the fearsome Frankish military decided against attacking Denmark itself.

Intimidated for the moment, Gudfred sought a political solution and entered into negotiations with Charlemagne. Their emissaries met but failed to conclude a peace agreement. Fearing further Danish incursions, the emperor installed a sizable garrison north of the Elbe River.

Both monarchs were displeased with the status quo. Charlemagne asked his subjects to pray to God for his victory over the Danish pagans while he drew up plans for a major expedition against Gudfred. The Danish king, on the other hand, was incensed at the Frankish garrison near his “front door” and looked for a way to circumvent it.

Viking as he was, Gudfred of course chose an approach by sea.

He allegedly gathered around 200 sails and, ignoring Saxony for now, attacked Frisia instead. The Franks had not expected this attack, so the province was only lightly defended. Therefore, the Danish seaborne army made quick work of the local troops and defeated them in three battles.

The Frisians saw no choice but to surrender. The marauding Vikings imposed a “tax” on them of 100 pounds of silver, to be paid on the spot. They rationalized this by arguing that Frisia was a province of Denmark, implying that Gudfred had the right to tax them.

Even a Frankish chronicler admitted that:

[Gudfred] was stuck-up by such a vain hope that he claimed the lordship over all of Germany; also, he did not see Frisia and Saxony as anything else but his provinces.

— Frankish historian, scholar and courtier Einhard (c. 775-840)

Charlemagne was of course infuriated by the second Danish violation of his territory. He gathered as much of his imperial army as he could to retaliate. Gudfred, grown bold by his success, boasted that he would face and kill Charlemagne in the open field.

However, before such matters could come to pass, the Danish king met his demise in typical Viking fashion. One of his close associates, perhaps afraid of the consequences of a protracted war with the emperor, murdered him. Gudfred’s nephew succeeded him and hastily made peace with the Franks.

The Danish threat to the Frankish provinces subsided for the time being. Charlemagne died four years later. The new emperor, Louis the Pious, invaded Denmark in 815 to place a christian claimant on the throne but was defeated by Gudfred’s sons.

Over the following decades, the Frankish Empire destabilized and finally imploded. Safely tucked away behind their Danevirke, the Danes could exploit the weakness of the Franks without fear of retaliation. Danish Vikings attacked, raided and plundered the Empire at will - mainly targeting the coastlines of modern-day France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

In 845, Danes cooperated with the legendary Ragnar Lodbrok to besiege Paris itself. Later, another group of Danes was even given a Frankish province, henceforth called Normandy - “land of the Northmen”. All the while, the Danevirke were an impervious barrier that shielded Scandinavia from reprisal attacks overland, augmenting the Viking dominance at sea.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

During the 10th century, as the Empire regathered its strength, defending the Danevirke became a mission of the utmost importance for all Danes.

Queen Thorvi, who reigned from 936 to 958, made every Danish tribe responsible for an aspect of the walls:

Thorvi’s son, king Harald Bluetooth - yes, our wireless technology is his namesake - upgraded the Danevirke even further. Under his rule (958-986), three additional meters were added to the rampart’s height. As it turned out, Harald had good reason to do so.

By then, the Frankish Empire had fallen apart. But its eastern flank had reorganized itself into the Holy Roman Empire in the first years of king Harald’s reign. And, even worse, its first dynasty was of Saxon origin!

As a result of Charlemagne’s campaigns two centuries earlier, the Saxons had ultimately been fully integrated into the Frankish imperial structure. The chaos and confusion of the disintegration of the Frankish Empire, then, allowed the Saxon kings to amass ever more power within the old imperial borders. When Charlemagne’s bloodline died out in the 10th century, the Saxons could legitimately claim the imperial title.

Two ancient threats to the Danes thus combined under Bluetooth’s reign: their pesky southern neighbors, the Saxons, had revived the old Frankish imperial claim of sovereignty over all of Europe.

The first Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I, used his newfound might to finally bring Denmark under imperial control. The power gap between the Saxons and the Danes was now so wide that Otto simply forced Harald Bluetooth to convert to Christianity without even needing to invade Denmark. The Danes grudgingly obliged and agreed to pay tribute to the Holy Roman Empire as well.

However, when Otto died in 973, king Harald leaped at the opportunity to free his people from the imperial shackles. He allied with the Norwegians and formally rebelled against the new emperor, Otto II. Before long, a Viking army once more invaded and ransacked Saxony - the heartland of the “Ottonian” imperial dynasty.

The Holy Roman Empire responded as fast as it could. Emperor Otto II marched north and met Harald’s combined Danish-Norwegian army head-on. To both monarchs’ surprise, the army of the Northmen actually defeated the imperial forces in battle.

But, much contented with the plunder of their campaign, Harald’s Norwegian allies returned home after the battle, leaving the Danes to fend for themselves. Otto II sensed an opportunity for revenge and attacked Harald’s army the next year. This time, the imperial military was successful.

After beating the Danes in battle, king Harald then witnessed what his predecessors had managed to avert for centuries: the enemy broke through the Danevirke! For the first time in history, soldiers of the Empire were on the northern side of the wall. To Harald’s great detriment, Otto II also conquered parts of Jutland in the wake of this catastrophe.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Again subjugated to the Holy Roman Empire, the Danes had no other choice than to bide their time. Fortunately for them, the emperor faced many foes. Within a decade, Otto II suffered a stinging defeat in southern Italy against the Emirate of Sicily.

Harald Bluetooth made the most out of the situation and quickly reconquered the parts of Jutland that had fallen under imperial control. Of course, he also reclaimed the Danevirke and the Danish-imperial border once again settled at this line. It would not move for the rest of his reign.

Having learned their lesson from the Ottonian antics, the Danes were acutely aware that they simply needed more to contend with their southern neighbors. Thoroughly looking after the Danevirke’s structural integrity was no longer going to cut it against the - now imperial - Saxons. The Danes needed an empire of their own.

Harald’s descendants, with illustrious names like Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut the Great, did exactly that during the early 11th century. By subjugating both Norway and England, they created the North Sea Empire. For a while, the kings of the Danes thus grew into Western Europe’s mightiest monarchs - after the Holy Roman Emperors, of course.

But the Danish Empire was short-lived, as Norway went its own way soon enough and Edward the Confessor brought the Anglo-Saxons back on the English throne one last time - until William the Conqueror invaded in 1066. Twenty years later, the Danish king planned on invading England, too, to reclaim what he deemed his birthright. However, the fleet never set sail because - you guessed it - the Holy Roman Emperor was waging war against Denmark at the time.

The ambitions of the Danish kings were thus constantly clipped by the imperial threat to the south. To be able to ignore the emperors somewhat, they greatly expanded the Danevirke during the High Middle Ages. Over the course of the 12th century, its moats were deepened and another two meters were added to its height, topping up the walls at a staggering seven meters.

These improvements provided security for the Danes for the rest of the Medieval Era. Even as late as the 19th century, the fortifications proved their worth. In 1864, Denmark went to war with Prussia and Austria over precisely the area surrounding the wall.

After a millennium of service, the border that the Viking kings of old had chosen proved its defensive potential once more. For a while, the Danes halted the Prusso-Austrian advance at this legendary line. As if the times of Gudfred, Thorvi and Harald Bluetooth had returned, the Danish army was once again fighting against German invaders from the top of the Danevirke’s ramparts.

But, unfortunately for Denmark, the weather was to the attacker’s advantage. A tough Scandinavian winter set in, freezing the marshes surrounding the Danevirke. This allowed Prussian troops to traverse the lakes to its side, circumventing the Danish defenses.

Thus the Danevirke fell, having blockaded or prevented southern invasions for nearly 900 years after emperor Otto II broke through. With their southern flank broken, the war deteriorated swiftly for the Danes. Before the year was out, Denmark sued for peace.

It formally surrendered the territory surrounding the Danevirke to the Germans. As a result, its remains are in German territory to this very day. Unsurprisingly considering the history of the “Great Wall” of Denmark, the outcome of the 1864 war is generally regarded as a Danish national trauma.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning - at no additional cost to you - we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Comments are closed.

this website is genuinely amazing.

Glad to hear it, Jayson. Thanks!

Spott on with this write-up

Thanks so much, Bettina!

Very well written article. Keep up the good work - i will definitely read more posts.

Great to hear that, Montufar!

By all means, help yourself to the rest. 😉