MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

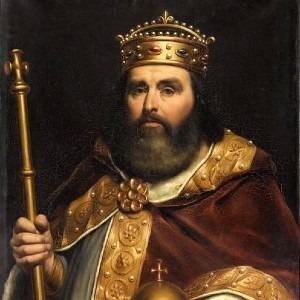

The Franks had done something terrible. Although there already was a Roman emperor, residing in Constantinople, the Frankish king Charlemagne had himself crowned as Roman emperor, too! This was not just a usurpation; it shattered Rome’s legacy, and indeed Christianity, forever.

The Franks, having hitherto called the emperor in Constantinople “Roman emperor”, now started addressing him as “Emperor of the Greeks”. The Eastern Romans, better known as Byzantines, were used to calling their ruler simply basileus – which by then meant “emperor”. For what other emperor was there?

However, confronted with this Frankish insolence, the (Eastern) Romans now had to address their monarch as basileus Rhomaíōn, “Emperor of the Romans”. To further underline his supposed superiority over the Franks, the basileus started styling himself as autokrator – a “ruler who rules himself”, i.e. who has no superiors. Of course, the (Eastern) Romans also viewed Charlemagne’s coronation as an insulting arrogation.

What did the Franks make of these condemnations coming from Constantinople?

Grab a 5-minute intro to the Holy Roman Empire and its rulers from our Medieval Guidebook.

Grab a 5-minute intro to the Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire from our Medieval Guidebook.

Having two emperors was paradoxical enough. Romans understood the imperial title to signify universal monarchy; the emperor was not just the ruler of the Roman Empire but over all mankind. Charlemagne’s coronation, therefore, created a contradictio in terminis: the Two-Emperors Problem.

In what must have been a relief to the (Eastern) Romans, the House of Charlemagne – the “Carolingian” dynasty – created its own destruction. Frankish law stated that a father should divide his possessions between his sons. This also applied to the Carolingian Empire, which was seen as the emperor’s personal possession.

Within a couple of generations, the empire disintegrated and although some fringe monarchs tried to keep the imperial title alive as late as 924 CE, the Western “Emperor of the Romans” was simply no more. The title was left vacant. In a seemingly lucky turn of events, the Two-Emperors Problem had solved itself – for a while.

Already in 919, the duke of Saxony, Henry “the Fowler”, had managed to become king of Germany, one of the successor states of the Frankish Empire. By defeating the Magyars and pummeling the Burgundians into subject status, he greatly increased his prestige. Now the undisputed ruler north of the Alps, Henry planned to claim the imperial title that was falling into disuse.

He died before he could complete his mission but his son Otto then launched the Saxons and Germany into the heart of European power politics. As it happened, the Kingdom of Italy – another successor state of the Carolingians – was in turmoil at the time. The political future of queen Adelaide, widow of the late Lothair II, was uncertain, with numerous suitors vying to become the next king of Italy.

Unimpressed by all of them, Adelaide turned her gaze north and invited the German king Otto to come settle matters south of the Alps.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Never one to let a golden ticket go to waste, Otto descended into Italy, defeated the squabbling factions, and married the queen in 951 CE. Yet, renewed raids by the Magyars drew his attention back north in the following years. Italy was left to vassals, who started scheming behind Otto’s back as soon as he had left the country.

Chaos returned to the peninsula posthaste. As early as 960, the pope petitioned Otto to return to Italy to reimpose political stability on the unruly nobles. The German king, having successfully subdued a Magyar invasion, crossed the Brenner Pass in August 961 and went straight for Pavia, the old Lombard capital.

There, he had himself crowned as king of Italy in his own right, rather than as king consort to his wife Adelaide. Continuing on, Otto was already in Rome by January 962. He took a decision there that would shape the politics of Europe for centuries.

Having accrued two royal titles, those of Germany and Italy, Otto deemed the time right to house them both into one, overarching, imperial construct. Since Charlemagne’s imperial title was still vacant, there was a perfect opportunity here to rekindle the Two-Emperors Problem in all its splendid menace. So, on February 2, 962 CE, Otto was crowned imperator Romanorum – “emperor of the Romans”.

Historians call Otto’s realm the Holy Roman Empire, to avoid confusion with the Roman Empire of Antiquity – or, for that matter, with the Carolingian/Frankish Empire of Charlemagne or the Byzantine/Eastern Roman Empire of Constantinople. But for Otto’s contemporaries, this was the Roman Empire reborn. (The term “Holy Roman Empire” did not come into use until the 13th century.)

So, what did the Roman Emperor in Constantinople think of this affront? First, the Eastern Romans had had to deal with upstart Goths in the 6th century; then with discourteous Franks in the 9th. Now the abrasive Saxons added insult to injury.

On top of that, imperial interests (that is, the aims of both Otto and Constantinople) soon clashed in southern Italy. Emperor Otto tried to expand his new empire even further south, but the Eastern Romans still claimed dominion over these lands. Otto even moved his capital to Rome in order to personally oversee his southern borders.

The Holy Roman Empire did not outright attack the Eastern Romans, though. Above all, Otto sought recognition of his imperial title by the court in Constantinople. So he sent bishop Liutprand to the East, aiming to negotiate a settlement.

But this envoy was staunchly anti-Eastern Roman, believing Constantinople had forfeited its claim to the West by failing to look after Italy and Rome when the Goths, Lombards and Arabs invaded it. He told the Eastern Roman Emperor:

“My master did not [tyrannically] invade the city of Rome. (…) Your power, I fancy, or that of your predecessors, who in name alone are called emperors of the Romans and are it not in reality, was sleeping at that time. (…) Which one of you emperors, led by zeal for God, took care to avenge so unworthy a crime and to bring back the holy church to its proper conditions? You neglected it, my master did not neglect it.”

— Bishop Liutprand in “negotation” with the Eastern Romans

Nikephoros II, emperor of the Eastern Romans, responded that Otto was a mere barbarian king, who had no right to call himself emperor, let alone “Roman”. Furthermore, the emperor openly described what he – and centuries of his predecessors – thought of the old capital Rome:

“The silly pope does not know that the holy Constantine transferred hither the imperial sceptre, the senate, and all the Roman knighthood, and left in Rome nothing but vile minions – fishers, pedlars, bird catchers, bastards, pleb[s], slaves.”

— Eastern Roman emperor Nikephoros II

Suffice to say that Liutprand’s mission was a diplomatic disaster.

Emperor Nikephoros was assassinated in 969, and succeeded by John I. Emperor John had military ambitions, particularly against the Arabs. As such, he was less interested in a row with the Holy Roman Empire about the proper titulary.

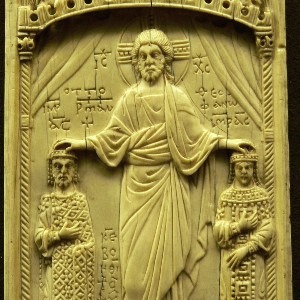

Before long, emperor John was engaged in confrontations with the Bulgars, the Rus’ and – most of all – the Caliphate and its emirs. Otto, now called “the Great”, felt the wind turning and tried his luck again. He drove a hard bargain and sought to marry his son and heir, Otto II, to an Eastern Roman princess. As Constantinople was already waging war on so many fronts, the Ottonians got what they wanted: in 972, future emperor Otto II of the Holy Roman Empire married princess Theophanu, niece of emperor John I.

One could be forgiven to think that this sealed the deal, that both empires now acquiesced in the existence of the other. Nothing could have been further from the truth: the Eastern Romans kept addressing Otto and his successors as an emperor (or basileus), but never quite spelled out “emperor of the Romans”, constantly irking the chancellery of the Holy Roman Empire. On top of that, in a game of one-upmanship with the West, the Eastern Roman emperors now started styling themselves as basileus megas – “(the) great emperor”.

Additionally, in internal documents, the Eastern Romans went even further and simply called the Holy Roman Emperors “King of the Germans”. For them, there was still only one, true emperor: the one in Constantinople. This may sound trivial to us, but this all was of paramount importance in an era where the emperor was also viewed as the leader of Christianity. (The popes were still weak at this time, though that would soon change).

Later during the 12th century, the Eastern Romans tried to play the Normans in Sicily off against the Holy Roman Emperor. They even landed an army in Southern Italy, the last Roman force in Western Europe, to stir up the hornet’s nest. The expedition was a failure and only managed to damage further the already icy inter-imperial relations.

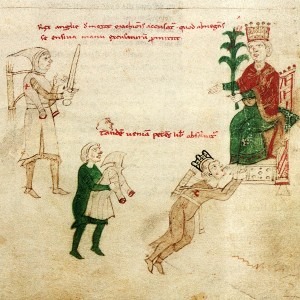

The Two-Emperors Problem was close to a nuclear meltdown in 1189 CE, when the two emperors would meet each other in person for the first time in history. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa was on crusade toward the Holy Land, and entered Eastern Roman territory on June 28. Eastern Roman Emperor Isaac II was unsure how to respond and panicked by giving conflicting orders.

What emperor Isaac was most afraid of was that the so-called crusade was actually a pretext for Barbarossa to invade the Eastern Roman Empire, abolish its imperial title, and solve the Two-Emperors Problem once and for all. And although Isaac didn’t want to provoke the Germans, he insisted on calling himself “Emperor of the Romans” in his official correspondence to the crusaders. This caused great offense.

To make matters worse, Isaac at first addressed Barbarossa in his letters as “King of Germany”. Realizing that this did little to improve the diplomatic crisis, he then started calling him “the most high-born Emperor of Germany” – at least assenting to the imperial titulary. As the stubborn crusaders pressed ever closer to his capital, Isaac at last started using the salutation “the most noble emperor of Elder Rome” (as opposed to the New Rome, Constantinople).

During the fall of that year, Barbarossa finally found out what Isaac was really up to. The Eastern Roman emperor had concluded a secret treaty with sultan Saladin to resist the crusaders together and was simply buying time. When the Holy Roman Emperor then received another letter from Isaac that – once again – browbeated Barbarossa as the “King of Germany”, he flew into a rage.

Barbarossa stated in front of all his troops that he was the one and only Roman Emperor. He also shared that he had realized that Constantinople had to be conquered for the crusade to be successful. The Holy Roman Emperor wrote to his son, who was still in Germany, to send reinforcements so that they might subjugate the Eastern Roman Empire together.

Isaac’s fears seemed to come true after all.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Barbarossa wintered in the Balkans and marched on Constantinople in the spring with renewed strength. Isaac now feared that he might lose his empire entire. He realized that he had pressed the issue too far and sued for peace.

The Holy Roman Emperor, ultimately intent on conquering the Holy Land rather than Constantinople, accepted. The treaty gave the German army free passage through the Eastern Roman Empire. Barbarossa marched on, towards Jerusalem, but drowned in a river in southern Turkey.

His son succeeded him as emperor Henry VI.

His main foreign policy became clear soon enough: he wished to hammer Constantinople into subject status. The insults directed at his late father gave him a casus belli to invade the Eastern Roman Empire. To improve his position, Henry also married a captive daughter of emperor Isaac to his brother, giving his family a dynastic claim that could prove useful in the future.

The Holy Roman Emperor then sent an embassy to Constantinople to establish his overlordship. The emissaries exponentially exacerbated the Two-Emperors Problem: they styled Henry as “emperor of emperors, lord of lords”. In a much-weakened state now, the Eastern Roman emperor relented and agreed to pay Henry a yearly tribute.

Henry was not done, however: he had plans to become the leader of the entire christian world, as any emperor should be. Henry envisioned himself as a true universal monarch. To press Constantinople into subject status was just a stepping stone for him to eventually have France, England, Aragón, Armenia, Cyprus and the Holy Land accept his suzerainty.

Henry VI succeeded in all this, and more. While both France and England accepted him as their nominal overlord, the Holy Roman Empire started constructing bases in Cilicia and Cyprus, which both had sworn to be Henry’s vassals as well. This began to look like a proper encirclement of the Eastern Roman Empire and caused great panic in Constantinople.

For the first time in Roman history, the Eastern Roman emperor downgraded his own title. Trying to appease Henry, emperor Alexios III of the Eastern Roman Empire started styling himself as simply (an) “emperor”, not necessarily “Roman emperor”. He also introduced the title of moderator Romanorum (“autocrat of the Romans”), not necessarily implying that there could not be others.

Although Henry VI died in the meantime, plunging the Holy Roman Empire into a succession crisis, the next Eastern Roman emperor – Alexios IV – tried to diffuse the situation further by playing a grammatical trick. He inverted the title and styled himself Romanorum moderator, which in Latin means even more strongly an autocrat of the Romans, implying that there could – indeed – be others. However, in the year Alexios IV’s reign ended, before all of this could take hold, Constantinople was conquered by the infamous Fourth Crusade.

Interestingly, the crusaders established a (Catholic) Latin Empire in its place. Its ruler was an emperor as well, giving the Two-Emperors Problem a new twist: now there were two Latin, Roman Catholic emperors in the world (rather than a Roman Catholic one and an Eastern Orthodox one).

If anything, this disappointed a lot of contemporaries and reinforced their notion that the problem would never be solved. Instead, the Catholic pope in Rome even propped up the new Latin emperors in Constantinople, because the papacy was now in conflict with the illustrious Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. A bit of inter-imperial rivalry was very much in the Church’s interest at the time.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

The Latin Empire collapsed as quickly as it was established and the Eastern Romans reclaimed their ancient realm. Faced with a relentless onslaught by the Ottoman Turks, this last line of (Eastern) Roman emperors sought reconciliation with the West. They did not even consider it an insult anymore to be called “emperor of the Greeks”, which Western monarchs of course loved rubbing in.

In the end, the Eastern Roman Empire fell in 1453 when the Turks conquered Constantinople for good. Although this is viewed as the end of the Middle Ages by some, the Two-Emperors Problem was far from solved. The Ottoman sultan claimed the title of Kayser-i Rûm (“Ceasar of the Roman Empire”), which brought him into immediate conflict with the – by then Habsburg – Holy Roman Emperors.

In the Early Modern Era, despite the competing claims uttered by the sultan, emperor Charles V of House Habsburg came close to becoming a universal monarch. As Holy Roman Emperor, King of Castile & Aragón, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy & Milan, Lord of the Netherlands, and in possession of Naples, Sicily, Sardinia and – barely explored but with seemingly endless potential – parts of Peru and Mexico, Charles saw himself as a second Charlemagne. For contemporaries, he seemed to succeed in realizing the Roman dream: to truly become emperor of the world.

The Habsburg Empire fell apart over the next few generations and to make matters worse, the Turkish example set by the sultan received its fair share of followers. Already in 1472, the grand prince of Moscow, Ivan III, married the niece of the last Eastern Roman Emperor and subsequently declared himself tsar (meaning “caesar”). Much later, in 1802, Napoleon introduced another imperial title: Empereur des Français.

Many of the inter-imperial disputes were solved in 1806, when – after 1,000 years of bickering, conflict and open war since the crowning of Charlemagne – it was Napoleon himself who formally abolished the Holy Roman Empire. The idea had caught on, though. Whereas the French turned back to a republic over the course of the 19th century, by the end of that era there were five emperors in Europe: the emperor of Austria-Hungary, the emperor of Germany (not the same as the Holy Roman Emperor!), the Russian czar, the Ottoman sultan, and Victoria – who was also empress of India.

To any sane Roman, whether this person was living under the reign of Theodoric the Great, emperor Alexios III or even Augustus himself, this would have seemed as if the world had gone completely crazy.

Featured Image Credit: CaptainVoda (deviantART)

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports, reviews and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Comments are closed.

Great post.

Glad to hear it, Humberto! Thanks.

Thanks for this informative website.

You’re welcome, Moses. Thanks for stopping by!