MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The mighty city of Ghent was one of Burgundy’s most prized possessions. But the relationship with its powerful Burgundian overlords was difficult, complicated and often tempestuous. How was one city able to be such a persistent and painful thorn in Burgundy’s side?

Grab a short intro to the Duchy of Burgundy from our Medieval Guidebook.

The dukes of Burgundy ran a splendid state in the 15th century CE. Its court was so magnificent it set the fashion for other European royal houses. It was the envy of many a monarch.

Politically speaking, the Burgundian State was a major power in Western Europe. The Burgundian dukes styled themselves as “Grand Dukes of the West”. All this came at a price, however.

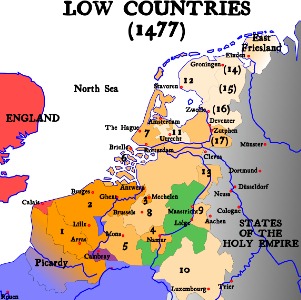

To sponsor culture so magnanimously and to be such a generous patron of the arts, the money first had to come from somewhere. As it happened, Burgundy had “acquired” many rich states in the Low Countries, most notably the County of Flanders.

During the High Middle Ages, Flanders had grown exceedingly rich through the textiles trade. Their prosperity had allowed its urban centers to act as nearly independent city-states.

Now, the Burgundian dukes tried to squeeze these cities, especially Ghent. This rich city (situated in present-day Belgium) turned out to be the greatest challenge to Burgundy’s power in the region.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

As always, matters came to a head over money. Duke Philip imposed a salt tax on Flanders. Salt was needed for food preservation as well as spicing up most dishes, so this tax hit everybody.

The city of Ghent rose in revolt. Its inhabitants formed a popular assembly to install revolutionary rule. In effect, the city was formally declaring its independence from its feudal overlord, duke Philip.

Because of its wealth, Ghent was very valuable to the duke. Unsurprisingly, the Burgundian army soon arrived in the region to subjugate the city. Ghent, however, was so rich it could afford the most powerful weapons of the Late Middle Ages: cannon.

The city’s artillery proved more than a handful for the Burgundians. Some strongholds in the region had remained faithful to the duke. The army of Ghent reduced them to rubble.

In the event, the new superweapons also proved to be Ghent’s downfall. On the morning of the decisive battle, both armies formed up, ready to charge. At that moment, a Ghent artilleryman accidentally dropped his torch in a gunpowder barrel. Terrified, a large part of the city’s army scattered in panic.

Consequently, the ducal army easily mopped up the resistance. Even for the mighty city of Ghent, death and taxes seemed to be certain.

To settle affairs and bring the conflict to a close, duke Philip used a ceremony that was immensely important at the time: the Joyous Entry. During such an event, the victor would enter the conquered city with a triumphal procession full of pomp and spectacle. The inhabitants would offer him tokens of power in return, formally subjugating themselves to the new regime.

Philip chose to have Ghent suffer this fate. In an age before mass media, Joyous Entries were meant to broadcast one’s power throughout the entire region. Attendees would spread the stories of its splendor throughout all neighboring towns.

The point of the ceremony was that the city where it took place could (re)state its devotion to its ruler.

Philip entered Ghent in 1454. Because the guilds had been at the heart of the rebellion, he ordered that they present themselves and publicly declare their loyalty to him.

Obediently, the guilds’ leaders offered their prestigious banners barefoot to the duke, who confiscated them. Furthermore, Philip ruled that guild decisions could be appealed against at the ducal court in Dijon. This essentially broke Ghent’s autonomy as Burgundian judges would now have the last say over the city’s affairs.

To top it all off, Burgundy took what it came for: money. Philip imposed a fine on the city. Its sum equaled the yearly revenue of all other Flemish cities combined.

“If I was to destroy this city, who is going to build me one like it?”

—Duke Philip of Burgundy showing his appreciation of Ghent, even after all that happened.

Ghent suffered terribly under these conditions. Its inhabitants had worked for centuries to amass great wealth. Now, a lot of it was simply transferred to the ducal coffers.

The city’s guilds, still at the forefront of its government, tried to renegotiate terms. They lobbied their duke for four long years. Ultimately, Philip agreed to revisit Ghent to settle matters.

Everybody in and near the city went out of their way to present him with the greatest Joyous Entry he had ever witnessed.

“If God had descended from Heaven, I do not know if the citizens would have paid him this much honor.”

—The Burgundian court chronicler quoting an attendee of the Joyous Entry in Arras.

Determined to outdo their rival city of Arras (see the quote above), Ghent’s inhabitants went all-in.

They covered the entire city with draperies. Hundreds of torches were lit along the way. Plays were enacted with over a hundred actors. A mechanical elephant spewed wine from its trunk. And a water show was conducted that recreated a storm at sea.

Impressed by the city’s efforts, Philip was able to play the forgiving and benevolent duke. This time, he went easy on Ghent’s inhabitants. Better terms were negotiated and Philip earned his nickname “the Good”.

Ghent had managed to regain some of its former grandeur. But (near-)autonomy did not return. The Burgundian dukes had tasted from the wealth of Flanders and would not let go.

After Philip the Good died, his son Charles – forebodingly nicknamed “the Bold” – wanted to shore up Flemish support for his reign. A week after the funeral, he organized another “Joyous Entry” into Ghent.

At first, everything went well. The new duke even pulled the bell rope of Ghent’s most important church – a time-honored tradition. After a long day, Charles went to bed content and confident that Flanders would obey him.

The next morning, things took a turn for the worse. A religious procession was entering the city. As they passed a customs office, a voice boomed from the crowd: “Down with the taxes!”

“Kill these spoilers of the world. Let us seek them out and slay them in their houses, those who have flourished at our pitiable expense.”

—Shouts heared in Ghent the day after Charles the Bold’s “Joyous” Entry into the city

Enthusiastically, the mob roared into action and demolished the tax office. Duke Charles came rushing from his hotel to inspect the situation. The rabble pressed in on him and forced him to flee into city hall.

An atmosphere of revolution once more descended upon Ghent. Seething with anger, Charles literally whipped somebody on the steps of city hall who he thought was egging on the resistance. When he wanted to lash out again, the city’s magistrates intervened:

“Do you think you can coerce a rabble like this by threats and hard words[?] They are beside themselves… You must try quite a different method—appease them by sweetness and save your house and your life.”

—The elites of Ghent talking duke Charles into a soft approach

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

After some deliberation, Charles asked Ghent’s citizens to put their complaints in writing. By doing so, he bought crucial time to gather his belongings, most notably his money and his daughter. When the petition arrived, the duke agreed to the demands, pardoned all involved and left the city.

Ghent’s victory seemed complete. Their success, however, inspired other cities in the Low Countries to revolt as well. When Charles the Bold arrived before Liège, also rife with rebellion, he unleashed his anger upon the city.

Its charters were declared null and void, its privileges were revoked, and its walls were razed to the ground. Liège changed from a mighty city into an undefended town. Flanders was in shock.

The city of Ghent understood this warning message all too well. An embassy of 53 of its guild leaders traveled to Brussels, where Charles was residing at the time. Still indignified over his (not so) Joyous Entry in Ghent, he let them wait barefoot and in the snow for an hour and a half.

When they were finally allowed to enter the audience hall, duke Charles was sitting on an elevated, golden throne. Fearful, the Ghent guild leaders literally cried “mercy”. Charles presented a paper copy of Ghent’s privileges and symbolically tore it in half in front of their eyes.

Burgundy was bent on breaking Ghent’s political autonomy forever.

In 1469, two years after the spectacular failure of Charles’s Joyous Entry, the Burgundian duke entered the city again. Everybody knew what was at stake here. Therefore, this time everybody behaved as expected.

Ghent was subjugated once again. All taxes were reinstated. First through ceremony, then through ferocious action, Charles the Bold had managed to whip Flanders into submission.

In the end, the events of 1454 (Philip the Good) and 1467 & 1469 (Charles the Bold) were far from the end of the Low Countries’ resistance to centralizing authorities. The cities and towns in the area were prepared to go to great lengths to defend their autonomy and privileges.

Charles’s only legitimate child, daughter Mary, ended up marrying the future Holy Roman Emperor. When Charles died, his son-in-law rapidly tried to assert his authority over Mary’s Flemish lands. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the city of Ghent immediately launched another insurrection.

The aftermath would set the stage for a long struggle during the Early Modern Era between the Low Countries and (the descendants of) the Holy Roman Emperor.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Comments are closed.

Nice to see the reference to Ruth Putnam’s biography of Charles the Bold.

Thanks for letting us know what you thought of it, Susan. It is a classic after all!