MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Can you imagine the sun disappearing for 18 months straight? A thick, impenetrable fog covering the greater part of three continents? A lack of shadows all around on account of the feeble light?

This was exactly what many people across Eurasia and North Africa experienced during 536 CE, habitually dubbed as the worst time to be alive - ever.

“A winter without storms, a spring without mildness, and a summer without heat.”

— Roman statesman Cassiodorus commenting on the weather

For ages, the remarks of writers living through 536 CE were treated as sheer exaggerations. Scholars and academics didn’t take seriously the fantastical stories about “the Year Without Light”. Contemporary comments, like that of Cassiodorus, were dismissed as overly doom-laden.

But recently, climatologists have been cooperating with archeologists to uncover an increasingly bleak picture of 536 and the subsequent years. Research into historical tree rings and ice cores more or less confirms the gloomy tales written down during this era. We now probably know more about the causes of this darkness than the people living back then.

As it happened, 536 was a time of unusual volcanic activity. Scientists found significant sulfate deposits in layers of ice dating back to this period. Several culprits stand “accused”: the Krakatoa in modern Indonesia, Rabaul in Papua New Guinea, or other volcanoes in North America or Iceland.

It’s beyond possible that - instead of one - a combination of these volcanoes erupted in or near 536.

In any case, a large amount of volcanic material entered the atmosphere and obscured the sunlight for months on end. This phenomenon is called a “volcanic winter“, and has actually happened several times throughout history.

536 was probably the worst volcanic winter to live through.

In the agricultural societies of the 6th century, these circumstances soon led to economic hardship.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

The ash cloud obscuring the sun had immediate consequences on living conditions everywhere. Early medieval economies relied heavily on sustenance agriculture: smaller-scale farms to provide for a couple of families - at most. In most civilizations at the time, there was a lack of large storage facilities for food. People produced their immediate necessities and little else. This economic order was highly vulnerable to catastrophes such as the 536 volcano eruption.

For starters, summer temperatures dropped by up to 2.5 degrees Celcius, starting the coldest decade of the past two millennia. (If 2.5 degrees doesn’t sound like a whole lot, recall how our modern governments are struggling to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees.) Contemporaries described the near-instant “global cooling” of 536 as “seasons jumbled up together”.

Snow fell in August in China. Droughts hit Peru in full force. Ireland fell into immediate famine.

Frost set in during harvest season, causing the apples to go sour. Soon after, widespread crop failure deprived many families of food. A “failure of bread” is a common remark in many annals covering these years.

In Scandinavia, Viking noblemen dumped hoards of gold into ponds and streams to appease the gods. The events of 536 may even have inspired the Ragnarok legend, foretelling the death of the gods amidst numerous natural disasters.

In any case, villages and empires across the globe were hit by the consequences of a sudden drop in temperature.

“[T]he sun gave forth its light without brightness … and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear.”

— Byzantine historian Procopius

As if one volcanic eruption wasn’t enough, more took place over the following years. In 539 or 540, a cataclysmic eruption occurred, possibly in El Salvador. Summer temperatures dropped by another, whopping 2.7 degrees Celcius.

Researchers think that the severe decline in temperature was the result of the volcanic material in the atmosphere creating a feedback loop:

To make matters worse, a third great explosion happened in 547. Taken together, these effects compounded to such a severe drop in global temperatures that climatologists label the 6th and 7th centuries CE as the Late Antique Little Ice Age: a century-long global temperature decline.

At first, the empires of the 6th century fared a little better than the sustenance farms and smallholdings elsewhere. The imperial Chinese, Byzantine and Persian civilizations, for example, were somewhat able to store food centrally in granaries and distribute it to their hardest-hit provinces. Meanwhile, inhabitants of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople eerily marveled that they could “see no shadows of our bodies at noon”.

But then, the Byzantine and Persian Empires in particular were hit by another calamity that truly made the mid-6th century the worst time to be alive.

While many people were already struggling to get by as a result of the bad harvests caused by the volcanic winter, a plague broke out in Byzantine Egypt. With a major part of the population on or over the edge of dearth and famine (and likely with weakened immune systems), the pestilence found a fertile “breeding ground” here. It spread rapidly to both the Persian heartland and the Byzantine capital.

The two empires suffered greatly under this first great plague pandemic of the Old World. With their intricate trade networks and large population centers, the disease swiftly raged through the Mediterranean world and the Middle East. Even the Byzantine emperor Justinian got infected, giving the epidemic its name of “Justinian’s Plague”.

Some scholars estimate that a quarter of the population in the region died during this outbreak, although other scientists have proposed far lower numbers. Recently, evidence also surfaced that the Justinian’s Plague spread far beyond the imperial realms, with Anglo-Saxon human remains from the 6th century apparently having contracted the disease. At any rate, this was a full-scale calamity.

So how did people cope with these bad tidings? Undoubtedly, many a prayer was conducted to beg the heavens above for a speedy return of the sun and a quick end to the plague. But surprisingly enough, life did not stand still and major events kept unfolding that put the Early Middle Ages in full swing.

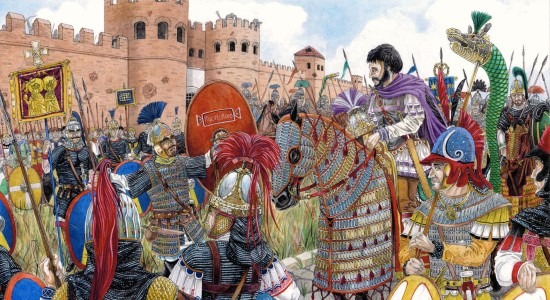

At the start of the worst year ever, 536 CE, emperor Justinian had just launched his great offensive into Italy to reconquer the western parts of the Empire which had fallen to the Goths. Volcanic winter or no, his star general Belisarius managed to eject them from Neapolis (Naples) and Rome before the year was out. As the Goths quickly gave way at first, perhaps the more superstitious among their ranks were frightened by the ominous portent accompanying Belisarius’s landing in Italy: the darkening of the sun?

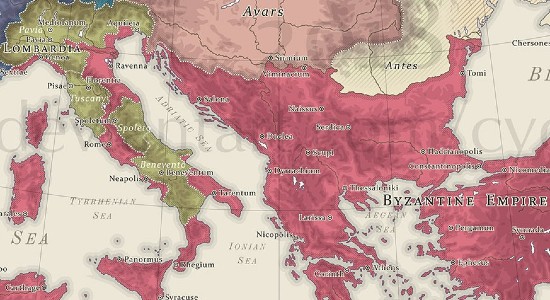

Either way, the subsequent disasters turned the tide of the war. While Justinian’s Plague (541-549) devastated and depopulated large parts of the Byzantine Empire, the Goths made the most of a bad situation and launched a counter-offensive that successfully lasted for over a decade. After the pandemic abated, however, the Byzantines reinforced their positions and finally conquered the entire peninsula.

Although triumphant, this victory came at a great cost. Because of its setback by pestilence, the conflict - by then named the “Gothic War” - lasted for nearly twenty years, sapping the Empire of crucial resources while it also had to deal with bad harvests on account of the volcanic winter. What’s more, the unfriendly climate hit globally, putting entire tribes on the move on most of the Byzantine borders.

As it happened, a second wave of the Migration Period broke loose. During the first wave, Franks, Burgundians, Goths, and so on, had moved into and gradually destroyed the Western Roman Empire. Now, new tribal confederations were looking to occupy the fertile lands of the Byzantine Empire - perhaps spurred on by disappointing agricultural results in their homeland because of the volcanic winter.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

The Germanic Lombards, for instance, invaded Italy only three years after what had seemed like the Byzantines’ total victory over the Goths. The Empire soon lost most of the peninsula to the invaders.

In the Balkans, the Slavs encroached on ever more territory, raiding deep into what is now Serbia and Croatia. These incursions turned to full-scale migration when the Avars swept in from the Great Eurasian Steppe and practically drove the Slavs further into Byzantine territory. War soon broke out between the Avars and the Byzantines, which turned into an even lengthier and costlier conflict than the Gothic War, whilst Constantinople also fought against Persia for most of the time.

The two-front war that the Byzantines fought would (much) later prove to be disastrous, when the global cooling of the Late Antique Little Ice Age turned out to have had bountiful effects elsewhere.

In Arabia, the lower temperatures made the area somewhat more hospitable, and more suited to agriculture. It’s not that the desert turned into a lush oasis overnight, but at least some parts of the region which had been arid ground before were now able to sustain livestock and grain. This led to a dramatic increase in fertility, exponentially expanding the population over the course of just a couple of generations.

This quickly turned Arabia into a population powerhouse. Fueled by its new creed of Islam, which was founded precisely during this period, the region now also possessed the manpower with which to challenge the two great empires of Late Antiquity: the Byzantines and the Persians. A century after the worst year ever, muslim armies had already conquered Palestine and most of Syria.

Many more Byzantine provinces would follow, as well as the whole of Persia.

The Early Medieval Era has often been described as the Dark Ages. While this terminology is fortunately no longer in use by most historians, it seems the events of 536 and the subsequent years might somewhat justify this nomenclature. As a result of several major volcanic eruptions, even contemporaries would have described the period as “dark” in a literal sense.

Some historians do call the 6th and 7th centuries CE the “Dark Ages”, not because of any presupposed ignorance, but for a simple lack of sources - making the era a difficult period to shed academic light on. Evidently, there were clear causes for people being busy with other things than chronicling. Rather than experiencing an overall “fall of civilization”, they had to deal with a volcanic winter, pestilence, bad harvests, and a lot of warfare.

But, as we hope you gathered from this piece, we should be careful to view the entire period as one of widespread devastation. The Byzantine government somehow thought the time was right for its Gothic War, and managed to sustain the conflict for two decades and win it. Further south, living conditions in Arabia - and probably other places, too - likely improved.

However, of all years, 536 CE itself does seem to have been the worst year ever, with weather distortions on every continent and global food supplies depleting within the span of a season.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning - at no additional cost to you - we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Comments are closed.

That is the proper blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You definitely put a new spin on a subject thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, simply great!

Thanks so much for your kind words, Zoritol. Glad you liked it!