MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Medieval cuisine featured a lot of food that would be familiar to us. But the medieval kitchen was also the origin of extravagant and elaborate culinary traditions that have since then gone out of style. Especially the better-off knew how to host a good banquet.

At first, refined food was quite sparse. Agriculture was aimed at sustenance rather than commerce. As such, most villages and hamlets would keep their own livestock. They would cultivate a variety of grains and legumes, with no expectation of trade or tribute. These sort of local arrangements lasted for as long as the locale remained “independent”.

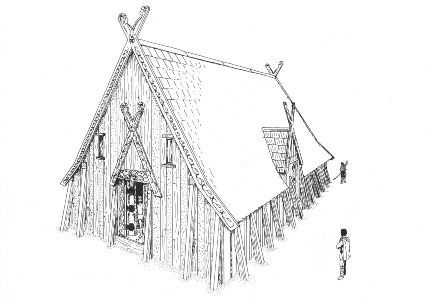

Nobles and chieftains were always on the lookout to communicate their status to society. They did so not as much by the food they ate, but in the way that their meals got to them. A perfect example of this was revealed when an Anglo-Saxon settlement in Cowdery’s Down was excavated, dated from roughly 600 CE. One of the buildings stood out from the rest. Its builders removed some estimated eighty tons of earth to construct it. They used some seventy more worth of timber to erect the structure. Its elaborate carpentry and layout suggest it was a great leader’s residence. Yet no signs of food production were found in the building itself. However, other buildings in the area did feature animal remains. Apparently, whatever noble household resided in the main building had their food tributed to them from their surroundings.

For the following five hundred years, the tables of bishops and dukes alike continued to be distinguished from those of peasants. The nobles did not perform the agricultural labor itself. They rather gave back to the community by way of protection and religious intercession respectively. Thus developed the three orders of medieval society:

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

A distinction in the nature of the meals consumed by the aristocracy began to appear as early as Charlemagne’s grasp over continental Europe fiercely expanded. His official biography, by one such Einhard, is telling. It reveals that the emperor, though generally of simple taste, ate what even at the time was deemed to be a lot of roasted meat - going against medical advice. Furthermore, the bureaucratic system he developed allowed him to substantially micromanage his many prosperous estates. Records from the time indicate that all popular foodstuffs in Europe would have been readily available to Charlemagne.

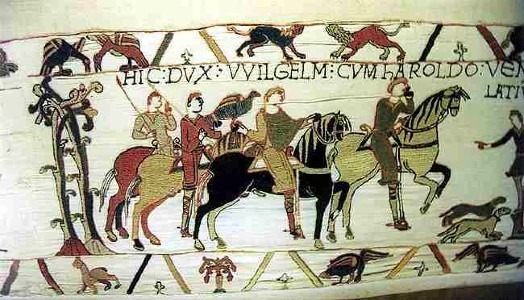

Einhard made no distinction as to what kind of meat the Emperor ate, though it is quite logical to assume it was some sort of game, like deer or boar. He references Charlemagne’s huntsmen bringing roasts on spits. On the other hand, even beef would have been enough of a status symbol, given the great quantity of grazing land required to maintain a steady meat-centered diet. Most European nobles followed Charlemagne’s style. By the 11th century, hunting was an integral part of the life of any nobleman, both for culinary and martial reasons.

Towards the year 1100, great magnates had consolidated power throughout most of continental Europe. The lands of the great lords of France, the Holy Roman Empire and the Low Countries had grown to be de facto petty kingdoms of their own. Improvements in agricultural technology - such as the wheeled plow and better harnesses for horses - made some of these dukes, counts and bishops fabulously wealthy.

The resurfacing of currency during the High Middle Ages played a significant role in this. The prevailing exchange in Europe derived from Roman currency but varied widely even within the same realm. There were 12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings in a pound. In thirteenth-century England, most nobles’ income was in the hundreds of pounds a year. The estates of great lords, such as barons and dukes, provided them with thousands of pounds of revenue every year. Knights, on the other hand, only earned a few dozen pounds from the lands granted to them by their lords. The appearance of tourneys later provided windfall gains for some of them. Yet to the average high to late medieval person, things were not as buoyant.

To put things in perspective, for most of the 13th and 14th centuries - and in times of peace only - unskilled urban laborers in Western Europe commonly earned roughly a penny. This was as close to a minimum wage as the medieval economy allowed for. This income would have permitted them a roof over their heads, some bread, other scraps of food, and mending their second-hand clothes every now and again. Any tumble in their field of work would have taken them to the streets and made them the subjects of charity.

Major changes in haute cuisine really took off in the 12th century. In the aftermath of the First Crusade, a commercial revolution took place. This, combined with agricultural improvements at the time, progressively made the rich even richer. Most European regions began to specialize in the production of certain goods. International trade expanded, with a class of urban risk-takers traveling far and wide to profit from this early sort of globalization. Aquitaine became England’s wine cellar, Northern Italy and Lower Germany became the continent’s forges, and Poland gradually turned to be Europe’s granary. Supported by stabler realms in Europe, a growing merchant class, and commerce with the East, the dining tables of the European nobility thus flourished in a spectacular manner.

The Crusading States allowed Italian merchants to more easily import luxurious spices. But the market offer, though broadened thanks to limited cultivation in Spain and southern Italy, remained in the hands of mostly Asian traders. Some spices, most notably saffron, were outrageously expensive given their labor-intensive production. Yet the aforementioned purveyors of spices were well aware of how fond European magnates were of these valuable condiments.

As such, they prized them accordingly, going as far as shrouding some in legend. In a stroke of marketing genius, Arab traders would justify the prices of cinnamon with a fictional tale. The spice was supposedly only found on the cliffside nests of some exotic birds, and to fetch it, the bird had to be lured, for some intrepid climber to hastily collect the costly bark strips.

By the 13th century, people started organizing banquets unlike anything seen before. The increase in wealth allowed for a host of different culinary workers to be employed in rich households. It also enabled nobles to purchase a near-endless range of consumables, whose delight was not only in flavor.

Between the years 1250 and 1400, a plethora of sources described how European nobles ate. From a castle’s expenditure records to the accounts of banquets in biographies, all pointed out the sorts of dishes served and the ingredients featured. The rich started eating much better food. For instance, the bread for aristocrats was often made with white flour, given how much labor went into sieving and refining the grains. Whereas most medieval people made do with bacon, a nobleman might routinely have eaten boar. On lent days, when only fish (which oddly enough included barnacle geese and beavers) was permitted, fish would have been served, stuffed with herbs and dusted with spices. As for sweets, fruit-filled pies were well known, and enriched with honey, whereas candied fruits first appeared as novelties by the turn of the 12th century.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

In the meantime, culinary staff developed into a household division of their own. An increasing number of castles featured different “departments” for each foodstuff, handled by specialized personnel. For instance,

At generous banquets, at least a dozen courses would have been served, with the jewel of the feast usually being an entire (expensive) animal. On special occasions, it would have been presented, roasted on a spit, in the lord’s hall, and directly carved above the fire. Boar was generally the roast of choice. Peacocks and swans were stuffed with their own meat and other fillers and then redressed in their own plumed skin. Pies encasing live pigeons or doves were simultaneously food and entertainment. Piglets, or newborn rabbits, might have been served as appetizers. These main dishes would have been intertwined with soups and stews, and every dish would have been spiced in one way or the other.

The evolution of medieval haute cuisine invariably involved the growth of the merchant class. Wealthy burghers were not far behind in taste from traditional landowners. For important occasions - weddings, holy days, birthday parties and the like - they would break from habitual broths, stews, and bread. For such events, these townsfolk, while having servants that prepared their everyday meals, would hire professional cooks and their staff -not unlike today’s catering services.

This was mostly out of a bourgeois desire to emulate the noble lords. As the Middle Ages progressed, a respectable number of burghers became evidently richer than many nobles. These merchants and tradesmen wanted to make clear to everyone, in what they ate and how they dressed, that they had made it in life. Thus, sumptuary laws appeared to curtail the burghers’ ability to host such extravagant meals or dress so flamboyantly that they may pass as nobles.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Staff salaries aside, the costs of foodstuffs in castles were high. When we look at the daily expenditures of noble lady Eleanor de Montfort, for instance, the sums seem staggering even for ordinary days. Two shillings and five pence for food on a Thursday, four shillings and seven pence worth of fish for a Sunday, with further kitchen expenditures shy of over one pound for that day alone.

On the more extreme end, even a lesser nobleman such as Bogo de Clare, third son of the 5th Earl of Hertford, was once able to offer a banquet for which the food expenditures were eight pounds and six shillings. In other words, a jaw-dropping 1,992 pence just on food, notwithstanding the prices paid for the feast’s entertainment.

“European” standard measures were nearly non-existent. Spices, for instance, as sought-after and expensive as they were, would be weighted, with well-regulated weights which varied from town to town. This usually meant that the most prosperous were those on top of the weight and monetary exchange rates. Prices for spices were inconsistent, to say the least. Whereas in Troyes, France, a pound of pepper might cost four shillings, in England it could have been less than one shilling. Meanwhile, cinnamon seems to have been a little cheaper, but saffron was worth more than its weight in gold.

It is common knowledge that when Christopher Columbus stumbled with the New World, he was literally and figuratively going against the current to find a shorter route to the Indies, in a quest for spices and gold. Despite some initial setbacks, with the conquest and colonization of the Americas, new foodstuffs gradually found their way to the old world. By the 18th century, they were near commonplace, and would later become essential in local cuisine.

One would be hard-pressed to imagine Italian cuisine without tomatoes, but the truth is, for most of history, that is how Italians cooked. Spanish tortillas are made mostly of potatoes, and paellas without peppers are unthinkable. Turkeys are a staple of English Christmas dinners, and the best chocolate is often attributed to the Swiss or Belgians. This goes to show that - deep down - our enjoyment of exotic foodstuffs is far from a thing of the past. Even in the culinary world, change seems to be one of the few constants of history.

- advertisement -

Comments are closed.

Thank you very much for your feedback, Lena! I think you may find this particular guide interesting: https://medievalreporter.com/guidebook/civilizations/rus/

Look forward to hearing your comments on that one!

Very informative and professional article with deep view on such an interesting topic. Enjoyed the content which opened so much new details. Thank you!