MedievalReporter.com

Master the Middle Ages in mere minutes

Join our newsletter!

The latest on history's most marvelous millennium

The latest on history's most marvelous millennium

The Knights Hospitaller formed an international network organization all over medieval Europe and the Middle East, with an uncanny resemblance to modern non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Although they were a religious military order, sworn to protect the weak and take care of the ill, the Order of the Hospitaller Knights grew from a “state within a state” to a rich, supranational organization spanning continents. This all happened throughout the High Middle Ages, but the Order’s characteristics as an NGO avant la lettre will seem all but familiar to contemporary observers of global affairs.

Over the coming weeks, we’ll shed light on this thanks to a guest essay by Pietro Battistella, a Singapore-based consultant and journalist who is passionate about history. The essay’s aim is to give an analysis that is largely historical, with a deliberately current perspective.

We have broken down this study into three parts:

The second and third parts will be published over the coming weeks.

The monks who founded the Knights Hospitaller had as their primary mission the care and treatment of ill travelers of a variety of religious backgrounds. Backed by papal permission, they established their order in 1113 CE as the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem - commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller.

Jerusalem, and indeed the entire Levant, was a focal point of a series of religious battles about control of the Holy Land. The city was first taken over by christian knights during the First Crusade in 1099 CE; however, sultan Saladin was eventually able to reconquer Jerusalem in 1187. At that point, the Order of Hospitallers moved its operations to the new capital of the Crusader Kingdom, Acre.

In 1291, muslim armies conquered Acre as well. They expelled the Knights Hospitaller once again. The Order then spent twenty years as a “guest” on Cyprus before participating in the conquest of Rhodes, where they remained for the following two centuries. During this time, they built on the island that is now part of Greece a legitimate sovereign territorial unit that exercised temporal, real-world authority; in other words, they founded a state.

From 1480 onwards, the Ottoman Turks frequently launched large-scale attacks on Rhodes. In 1522 their sultan Suleiman the Magnificent finally managed to conquer the island. Giving the Knights free passage to leave, the Order marched out of Rhodes in full battle armor, with banners held high and beating loud drums. The Hospitallers struck down on Crete and Sicily for a couple of years but moved to Malta when Holy Roman Emperor Charles V granted them the island as a new home in 1530.

The Hospitallers flourished on Malta for over 200 years, when a new danger emerged in the form of general Napoleon Bonaparte, who conquered the island in 1798. He ejected the Order from the island, after which some Hospitaller Knights tried to set up shop in Russia. This lasted only for a while: in 1834, the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta (as it was known, by then and now) was re-established in Rome.

To this day, the order continues to operate from the Italian capital. It is considered a sovereign entity by international law and maintains diplomatic relations with many countries. The modern Hospitallers employ over 50,000 doctors, nurses and paramedics in more than 120 countries, assisting children; the homeless, disabled and elderly; terminally ill people, refugees, and lepers - all without distinction of ethnicity or religion.

Tip: Grab a more in-depth explanation of the history of the Hospitallers here.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

The Knights Hospitaller were founded in the Holy Land and then relocated to Rhodes, Malta and Rome. On Rhodes and Malta, the Hospitallers established what may be referred to as a state, as such, in charge of a territorial area. The Order was always organized around a location like that (whether the Holy Land, Rhodes, Malta or Rome).

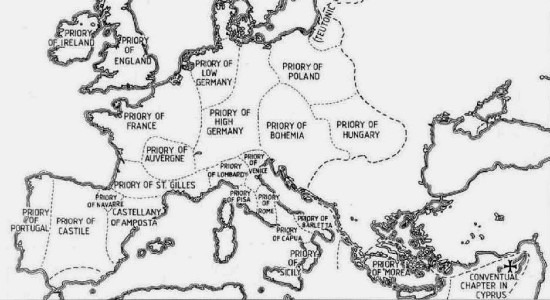

That location served as the hub of a network - a headquarters, if you will. The network’s reach, however, extended far beyond that specific place. Using the Order’s residence in Rhodes as an example, its possessions extended to the adjacent Dodecanese islands. Furthermore, in mainland Europe, Hospitaller possessions could be found in numerous European nations, including France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Denmark, England, and Hungary.

The administration of these assets was under the exclusive supervision of the Grand Master, but his authority was integrated with two elements: a collaborative one and a dependent one. Both the Chapter General and the Grand Master’s Council - two of the Order’s collegial bodies - reflected the collaborative aspect. The pope, who held ultimate authority over the Order, represented the dependent element.

The two local administrative divisions of the Order’s substantial estates were the commandery and the preceptory. A preceptory was ruled by a prior and had a variable number of commanderies. Most preceptories were far away from the Order’s central seat. The Knights Hospitaller tackled this by requiring priors to visit the Grand Master every five years to brief him on the latest developments. The rule was often infringed upon, as the journey from most priories to Rhodes was arduous and dangerous. So the Chapter General of 1301 stipulated that at least two priors should visit the Grand Master each year; in 1370 it decided to increase this number to three.

A Hospitaller prior, then, appointed the leaders of his commanderies in consultation with a provincial council. The priory collected income from these commanderies and forwarded most of it to the Order’s headquarters. A prior was expected to tour his province regularly. Priories of the same “country” (like England or Italy) were sometimes brought together under a magnus praeceptor, or “grand commander”.

This management system was simultaneously the Order’s most important asset and its greatest weakness. It filtered material resources, on which the Knights Hospitaller were strongly dependent, to the top. This allowed Grand Master, Chapter General and Grand Master’s Council to keep expanding the order.

During the Rhodes era, the Chapter General often convened on the island itself. The Chapter had a range of duties and powers, such as announcing new laws, handling promotions as well as disciplinary actions, and taxation. It could also summon Hospitaller Knights to the East, send visitors to the priories, and threaten depositions.

Over time, Southern France rose in importance as a meeting place as well, indicative of the dominance of French knights during the vast bulk of the Order’s existence. The official Lieutenant in the West was seated there, and the Knights Hospitaller sported so-called cardinal-protectors in the papal curia at Avignon. There was also a Receiver-General in the Languedoc, who became the main channel through which to transfer funds to Rhodes - oftentimes using Florentine bankers.

Additionally, something resembling a law school was even set up in Paris to train aspiring Hospitaller bureaucrats to excel in this system.

If the Order was a network, the priories and commanderies served respectively as its primary and secondary nodes, giving strength to the organization. Not all primary nodes were equally important, though. Compared to priories in Portugal, Ireland, or Poland, priories in France, Spain, and Italy were more active and situated closer to the Order’s core. They had a significant impact on the center’s resources, including personnel, money, and supplies - and thus had more influence on its decision-making.

However, it’s worth highlighting that the Knights Hospitaller were not a tightly controlled network, since nodes had considerable de facto autonomy. They could, for example, reject or fail to respond to instructions. A lack of tightness in the network might also be seen as a result of the absence of technological control mechanisms, which are typical of many contemporary network organizations.

Today, it is widely recognized that a modern globalization process has facilitated the emergence of several new and shared identities across different parts of the global population. These identities are basically transnational or location-neutral. It is the case of the social and cultural movements whose scale and impact rose as a consequence of globalization-driven advances in mass communication. Obviously, it is also the case for certain online communities.

However, the majority of the research on supranational identity has come from European studies. The growing integration of the continent has prompted discussions about the European Union’s and its member states’ shared sovereignty as well as the idea of a common identity of “the Europeans”. In this context, several researchers are using the concept of supranational identity to explain the linkage between national identities and the European polity.

Interestingly, the national identity is also under threat from the lower level. Localist or separatist movements, for example, sometimes aim to shape an ever-larger portion of the national identity or even to establish a brand-new, more limited national identity. In short, it’s not an exaggeration to state that the national identity concept based on the Westphalian State is under pressure from above and below.

How do the Knights Hospitaller help us to understand this change in contemporary, non-national identities? The Order did, after all, embody a supranational identity that is difficult to grasp by today’s standards. It was an international organization - although there were no nation-states as of yet - with members from all over Europe. The different heritages were clearly delineated, not so much by ethnicity but by language. That’s why the Knights Hospitallers were divided into linguae (“tongues”).

Each lingua maintained its own inn on Rhodes. There, members who spoke the same language could assemble. Every lingua‘s leader was a high officer within the Order, entrusted with specific duties. At least four such leaders had to be present on Rhodes at all times. And none of the others were allowed to leave without strict permission from the Council.

The Order itself transcended these national identities by pursuing higher recognitions in a religious sense (loyalty to the Pope), a military sense (the defense of Christendom), and a moral sense (attending to the sick). There were, so to speak, greater callings than one’s tongue. As a result, the linguistic identities of the Knights were nuanced; it is safe to assume they perceived themselves as belonging to both the Order and their respective “nationalities”. We use this term cautiously here since it would be incorrect to conceptualize nationalities in the Middle Ages using current standards; the majority of European nation-states, after all, developed their national identities (much) later.

The Knights Hospitaller managed to foster a strong sense of belonging and kinship for its members. Rigid social stratification and hierarchy were the main factors in the creation and management of religious military organizations, and this Order was no different. The tight adherence to hierarchy and stratification helped the Order develop a sense of community. A collective identity that may be regarded as supra-national rather than international or crossnational was produced precisely as a result of mixing national and beyond-national affiliations.

After all, one of the Order’s older mottos was pro fide pro utilitate hominum, meaning “for faith and for service to humankind”.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Another element of the Order’s organizational history that is very pertinent to current problems and trends in global affairs is that of sovereignty and jurisdiction. Today, as we have mentioned, the supposed weakening of the nation-state by many influences is a frequent subject of study and debate. There are analysts who study future scenarios of the world order that do not rule out a scenario known as “Neo Medievalist”. This would be a world in which the concept of authority resembles certain aspects of that of the Middle Ages.

What this would mean, for starters, is that the majority of authorities conceptually descend directly from the divine. But more importantly to our analysis, there were multiple levels of medieval power that were not clearly delineated on a practical basis. Both the Holy Roman Empire and the Roman Catholic Church, for example, claimed to be global political institutions yet shared power with lower-level entities like vassals and bishops. In a sense, most institutions possessed a shared authority at best and no one was entirely and solely sovereign - although many tried to be.

The Knights Hospitaller offer a prime illustration of this intertwining of sovereignty. The jurisdiction to which the Order and, in actuality, the majority of its members were subject was complex due to its network organization and multi-layered identities. The Order was governed by its own laws while also being under the pope’s control, who occasionally intervened. Additionally, the Order benefited from considerable financial exemptions in other territories. In the Middle Ages, in fact, the Catholic Church in Europe gathered a levy known as a tithe that was distinct from the monarchs’ levies. (Tithe means “one-tenth”, because people were supposed to give the Church one-tenth of all the income they earned.)

Under specific circumstances, the Order was exempt from the payment of tithes. This was so arranged because the Knights needed their independence to fulfill their mission. The burden of secular taxation and the meddling of jealous bishops would have been unwelcome constraints to the Order’s success. Furthermore, their supra-national organization meant that Knights Hospitaller needed freedom of movement, unbound to the territory of this king or that emperor.

On the other hand, the creation and existence of such privileged orders - as the Hospitallers were far from the only ones - created challenges for the Church. Their status aparte undermined the position (and the income!) of the clergy. The Orders were exceptionally useful tools for the papacy, but by sustaining them, the pope risked creating two parallel power structures that threatened to cannibalize each other. Unsurprisingly, disputes between the Knights Hospitaller on the one hand and both the secular and religious authorities on the other were a common occurrence.

Finally, the different linguae of the Order constituted a corporation with a juridical personality. The tongues themselves could literally hold and lease property, receive incomes and endowments, appoint procurators, establish foundations, maintain records, and so forth. Of course, the priories and commanderies belonging to the lingua were subjected directly to the Hospitaller authorities and excluded from the jurisdiction of local sovereigns - much to the chagrin of many a medieval monarch.

In the next episode of this series, we’ll look into the Order’s moral mission, its health management strategies and its medical legacy!

Featured Image Credit: Marco Zanoli (Wikimedia)

- advertisement -

- article continues below -