MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The French appeared from the ashes of the earlier Frankish Empire. As imperial authority collapsed, the empire’s western part reformed as the Kingdom of France. This didn’t stop the decentralization process, however. The first centuries of French history were exceedingly feudal: noble lords squabbled while serfs tilled the land. The King of France, meanwhile, ruled Paris and its surroundings but not much more.

Later, the royal court managed to accrue more power and France experienced somewhat of a renaissance. A new, Gothic architectural style developed. Universities sprung up across the country. And the new genre of chivalric romance gave French culture an immense boost.

In due course, the rise of France brought it into conflict with its neighbors, most notably England. The French fought a protracted conflict, called the Hundred Years’ War, with the English kings. The confrontation brought France to the brink of destruction, but the French kings triumphed in the end.

This is a short intro from our Medieval Guidebook. Dive deeper into the subject by reading our articles about it.

France rose from the turmoil surrounding the disintegration of the (Frankish) Carolingian Empire during the 9th and 10th centuries CE. The Carolingian dynasty had briefly ruled from Normandy to Austria. But the imperial structure soon began to falter. The grandsons of the famous emperor Charlemagne split the empire in three. Initially called West Francia, the western part evolved into the Kingdom of France as the 10th century progressed.

Central authority continued collapsing as this process continued. Remote areas such as Catalonia barely felt the influence of the king. North of the Pyrenees mountains, too, feudal lords established an ever-increasing autonomy from the royal center. Meanwhile, intensifying Viking raids plagued the kingdom enormously. The king even turned over an entire duchy, henceforth aptly named the Duchy of Normandy, to a Norseman called Rollo.

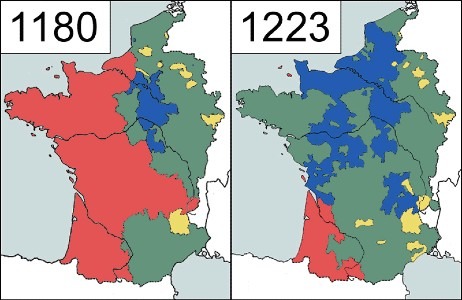

In 987, Hugh Capet managed to definitively wrest control of the West Frankish crown from the Carolingians. Although Hugh was related to them, his ascendancy to the throne marked the beginning of a new dynasty: the Capetians - named after Hugh. Their reign is usually marked as the end of the (Carolingian) Frankish period and the start of the (Capetian) French period. In reality, things were less clear-cut and the Capetian era is better understood as a transitory period. Only from 1180 onward did the Capetians style themselves as “Kings of France” - up until that point, they all identified themselves as “King of the Franks”.

In theory, the Capetian dynasty reigned supreme. However, in practice, during the beginning of the High Middle Ages, their authority was exceedingly limited. Noblemen ruled the land. Especially the mighty dukes, of Normandy, Aquitaine and Burgundy, for example, enjoyed independence in all but name.

If Hugh Capet traveled beyond his relatively modest dominions between Paris and Orléans, he risked being captured and ransomed. Indeed, a certain archbishop devised precisely such a plot, aiming to deliver the king into the custody of the Holy Roman Emperor. The plan failed but - tellingly - nobody was punished.

Fortunately for France, the Capetian dynasty featured a string of successful kings. Over time, they managed to check the power of the nobles and aggrandize their authority. Whereas French noblemen had played a major role in the First Crusade, French kings took the lead in many later crusader expeditions. The rise of royal authority brought the French into conflict with other European powers. The Angevin Empire, ruled by the kings of England but controlling roughly half of France, took up the mission of nipping France’s ascendancy in the bud.

Unfortunately for the English, the ambitious and exceedingly effective French king at the time, Philip II ‘Augustus’, managed to triumph. The English king John so spectacularly failed in curbing the rising power of France that his barons forced him to sign the famous Magna Carta. The Kings of France emerged from the conflict more powerful than ever. They reined in the power of the nobles and started centralizing the French state. A major factor contributing to their successes was the continued support of and by the Catholic Church.

To underline this relationship, the pope declared Philip II’s grandson, Louis IX, a saint - the only French king to receive this honor.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Philip Augustus and his successors oversaw somewhat of a Golden Age for France. Architects pioneered new “gothic” architecture that quickly caught on across Europe. Paris, Montpellier, Toulouse and Orléans founded universities. And troubadours contributed to the dawn of French literature with the genre of chivalric romance. But on the horizon, crisis loomed.

The tensions between France and England had not subsided. When the French king Charles IV died in 1328 without brothers and sons, a succession crisis ensued. His nephew - the English king Edward III - pressed his claims to the throne. This, however, was the last thing the French nobility was willing to accept. They presented their own counter-candidate, provoking a war between the two camps by 1337.

The conflict dragged on until 1453 (so its name as Hundred Years’ War is technically incorrect) but was not significant just because of its length. By the end of the war, professional troops had replaced nearly all feudal armies in the region. France reintroduced a standing army, a concept not seen in Europe since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. In the meantime, artillery took over the dominant role of heavy cavalry on the battlefield. Moreover, the long struggle stimulated the rise of a French and English ‘proto-nationalism’.

The French monarchy nearly succumbed under the weight of the war, but it ultimately “won”. This was partly thanks to folk heroine Joan of Arc, who scored a number of impressive victories during one of France’s darkest hours. In the end, the nobles of England lost almost all their continental holdings to France and - outraged - rose in revolt. In the meantime, the English Exchequer was nearly bankrupt on account of the Hundred Years’ War, whereas a century of conflict combined with epidemics and famines had devastated France.

The question could be raised whether this epochal family feud - the French and English royal houses were related - knew a victor at all.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Grab a short intro on another civilization from our Medieval Guidebook.