MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The English came forth from the Norman invasion of Anglo-Saxon Britain in 1066 CE. The invaders, a Viking/French hybrid themselves, mixed and mingled with the Anglo-Saxons, who had invaded the island some six centuries earlier. During the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries, this all fused into a new civilization: the English.

Through the Norman connection, their fate was intertwined with that of the French. In practice, this led to a centuries-long struggle - a war that the English ultimately lost.

This is a short intro from our Medieval Guidebook. Dive deeper into the subject by reading our articles about it.

During the Early Middle Ages, England was mostly divided between several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Later, Viking invaders established various realms on English territory. The last Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Confessor, spent much of his childhood on the run from Vikings. He went into exile in Normandy - a region of Francia given to the Vikings or “Northmen”, hence the name. Edward developed an almost familial relationship with the Norman duke, William.

Edward eventually returned to England to rule as the righteous king of the English for over 20 years. But when he died childless in 1066, his friend William - the duke of Normandy - laid claim to the English crown. He built a large fleet, crossed the Channel, and defeated the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Hastings. On Christmas Day, 1066, William was crowned king of England. We know him as William the Conqueror, and his invasion and subsequent crackdown of Anglo-Saxon rebellions as the Norman Conquest.

To impose their authority and intimidate the local populace, William and his successors built tons of castles, mostly in the famous “Norman keep” format. The Normans greatly centralized the island’s government, which stimulated economic growth. At first, they formed an occupying “upper layer” of society, which spoke French, was quite focused on continental politics and art forms, and fought on horseback - in contrast to the Germanic shield wall wielded by the Anglo-Saxons. Over time, the Norman aristocracy blended with the Anglo-Saxon “lower layer” to create a new hybrid culture: the English. Relics of this culture gap are found throughout the English language, in which cows (akin to the German Kuhe) roam the meadows yet produce beef (from the French boeuf).

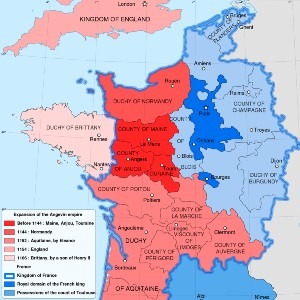

For most of the 12th century, England was actually part of a much larger realm: the Angevin Empire. William and two of his sons ruled the English until 1135, when the direct line of the House of Normandy died out. The son-in-law of the last Norman king of England was also count of Anjou, a region in western France. After a 15-year chaotic civil war, aptly named The Anarchy, he became England’s next king. He founded the Angevin dynasty, named after this Anjou power base.

The Angevin Empire, with illustrious monarchs such as Richard Lionheart, was a composite state that stretched from the Pyrenees to Ireland. The Angevin kings - although rulers of England - spoke French and spent much of their time in their continental holdings. As they held more land in France than the French kings themselves, the two crowns became natural rivals. After careful preparation, the French delivered the death blow to the Angevin Empire in 1214. The Angevin/English king John Lackland was then forced by his barons to sign the Magna Carta, which severely limited royal authority and is one of England’s de facto “constitutions“.

Having lost their continental possessions save Aquitaine and Gascony, the English kings now started to focus more on England. The power struggle with the barons continued, frequently leading to civil war. When this was finally (somewhat) settled in the mid-13th century, the English monarchy looked to Scotland and Wales to expand their domains. The Scots twice thwarted annexation by England but nevertheless suffered huge losses. The Welsh were subjected to an English castle-building program that escalated into colonization, just like the Normans had done to the Anglo-Saxons two centuries hence.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Remember how William the Conqueror, duke of Normandy, became king of England? His successors kept combining the two titles, but this created all sorts of problems. As it happened, the duke of Normandy was formally the vassal of the king of France, which meant - in theory - that the king of England (the one and the same person as the Norman duke) was subject to the king of France. Unsurprisingly, this did not sit well with the English kings. It sowed the seeds of centuries-long conflicts about who was superior.

After the collapse of the Angevin Empire and the loss of Normandy, the English continued their fight from Aquitaine and Gascony - in the south of France. The two powers balanced each other out for over a century, but in 1337, a disastrous turn of events occurred. The French king died childless and - as his brother-in-law - the English king Edward III was named as one of his successors. The nobility of France vehemently spurned his claim and put their own (French!) candidate forward. Of course, war broke out almost immediately to press both claims: it would last over a century and is therefore called the Hundred Years’ War.

The conflict ended terribly for the English. Although France at one point was one the verge of collapse, ultimately England lost all its continental possessions save Calais. But back home, a process that was long underway accelerated: the Norman and Anglo-Saxon elements of society completely fused into a proper English identity. The war with the hated French consolidated a narrative in which all of England cooperated to defeat the foe. Consequently, the nobility now started speaking (Middle) English rather than French and one Geoffrey Chaucher wrote The Canterbury Tales precisely during this period - and in English!

It wasn’t all moonlight and roses in late medieval England, however. Having lost the war with France, the authority of the English monarchy was at a low ebb. To complicate matters, two rival branches of the royal house disputed each other’s right to rule. In 1455, they took up arms in a civil war known as the Wars of the Roses. The conflict is named after the emblems of the two factions, the white rose of House York and the red rose of House Lancaster.

A complicated power struggle ensued in which both sides fought a string of pitched battles. After a while, the leader of the Yorkists - king Edward IV - seemed able to subdue the conflict through sheer military force. The Lancastrians laid low for a while, but when Edward died in 1483, the conflict flared up again. They now put forward Henry Tudor as their leader, who sought help from an old enemy: France. Through this alliance, Henry was able to beat the House of York.

He ascended the throne as Henry VI, and founded the Tudor dynasty. By marrying Edward IV’s daughter, he also combined the Yorkist and Lancastrian claims, definitively solving the succession crisis. The Tudors led the English into the modern era, with illustrious figures such as Henry VIII, “Bloody” Mary and Elizabeth I.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Grab a short intro on another civilization from our Medieval Guidebook.