MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Ever wondered what happened to Rome after – you know – the Fall of Rome? Did the Middle Ages simply start the next day? Were the last Romans turned into “barbarians” overnight?

Fortunately for us, the transition was way more interesting than that.

Grab a short intro to the Byzantines from our Medieval Guidebook.

Rome, capital of the greatest empire of Antiquity, fell to the invading Goths in 476 CE. They didn’t transform the Eternal City into the center of their new kingdom, however. After the Gothic conquest, there were still plenty of Romans in Rome – and many more to come.

As a matter of fact, the crumbling Roman Empire had earlier been split into two halves. The Western half remained centered around Rome. It was ended by the Goths when they took the city. The Eastern half carried on with Constantinople as the new capital. (The Eastern Roman Empire has been called the Byzantine Empire since modern times.)

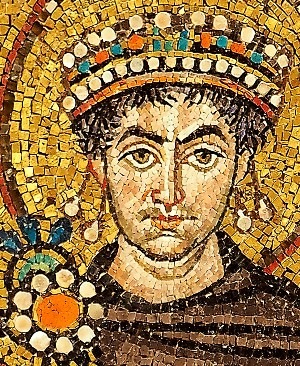

Half a century after the Western Roman Empire had fallen, an ambitious emperor ascended to the Byzantine throne. His name was Justinian. Under his reign, the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire sought to reconquer as much as possible of the late Western Roman Empire.

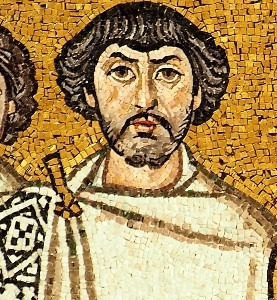

Justinian wanted to undo the Fall of Rome. Therefore, he sent his star general Belisarius to Italy to reclaim what had been lost to the Goths. Although commander-in-chief, Belisarius only had 7,500 men at his disposal for this arduous task.

Six centuries earlier, Roman general Julius Caesar had invaded Gallia with over 30,000 men. Belisarius’s detachment was obviously rather modest. The Byzantine general needed to be creative and achieve much with little.

He would employ cunning as well as deceit throughout the Gothic War – as the conflict came to be known. In the first phase of the war, however, Belisarius chose speed as his weapon of choice.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

General Belisarius landed in Southern Italy in 536 CE. The city of Naples immediately proved to be a major obstacle. It had been part of the original Roman Empire since 326 BCE. But the city decided to resist this Eastern Roman invasion anyway.

The Byzantines were determined to score quick results before the Goths in Italy could muster a response. So they stormed Naples after a siege of three weeks. Having been a core city of the Roman Empire for over eight centuries, it was nonetheless sacked by its new Eastern Roman masters. Belisarius had no time to lose.

Rome was next. It had now been sixty years since the Goths sacked the city. Unwilling to undergo such a fate again, the old capital surrender to the Byzantine army without a fight.

Within a year, Belisarius had achieved a great goal. Rome was back in (Eastern) Roman hands. Belisarius’s sovereign, Justinian, was once again Emperor of Rome and Constantinople.

The Goths, however, were outraged by the lightning successes of the Byzantine army. At the time, their king was quite the budding philosopher. He was interested in books and poetry.

The Byzantine offensive required a different skillset of a Gothic monarch, though. Support for his reign quickly crumbled. He was deposed before long.

The new Gothic king, Witiges, had a different philosophy altogether.

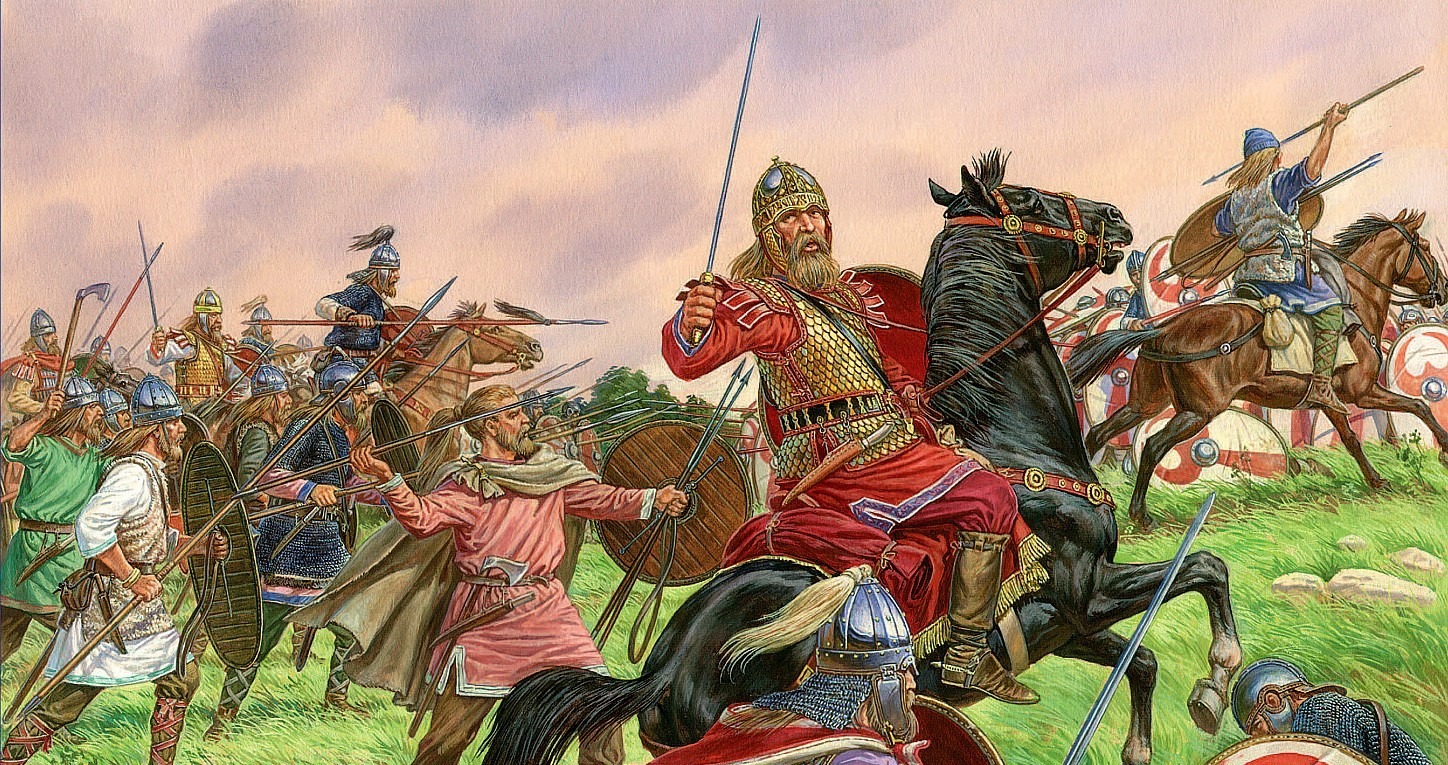

Witiges launched a counter-offensive as soon as he could. Determined to kick the Byzantines out of Italy, he assembled a huge host. It greatly outnumbered the Byzantine expeditionary force. The Gothic army promptly laid siege to Rome once again.

Belisarius and his soldiers were trapped inside the city. Because the Gothic army was much greater, he was unable to beat his enemy in the open field. He decided to wait out the siege.

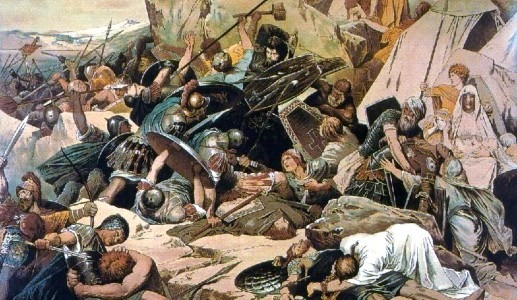

The Goths started building siege towers and rams. This caused a major panic among the Roman population. Belisarius, armed with a wealth of experience from earlier wars against “barbarians”, laughed at the machines. He remained unfazed. The general ordered everybody to calm down.

It soon became clear why. The Gothic army used oxen to move the siege engines forward. As they approached the walls of Rome, they also brought these animals within bowshot of the Byzantine defenders. Belisarius ordered his archers to kill the animals.

With nothing alive to carry them forward, the rams and towers stood useless in the middle of the field. Witiges’s attack had been stopped dead in its tracks. As a result, the Byzantines would be able to hold out a little longer.

“[T]he Romans were struck with consternation at the sight of the advancing towers and rams. (…) Belisarius … began to laugh, and commanded the soldiers to remain quiet and under no circumstances to begin fighting until he himself should give the signal.”

—Contemporary historian Procopius in De Bello Gothico (‘On The Gothic War’)

Despite their successes, the situation for the besieged remained alarming. The Byzantines possessed as few options as the Goths now did. With speedy offensives no longer being an option, general Belisarius decided to play other cards from his deck: distraction and deceit.

As winter fell, operations in and around Rome came to a standstill. Smaller-scale clashes beneath the walls – common after the failed siege attack – were no longer seen. The Byzantines used this lull in the fighting to sent a cavalry detachment up north.

The goal of this maneuver was to threaten the rear of king Witiges. With so many Goths concentrated in force at Rome, the Byzantine distraction force had an easy time capturing Ariminum – presently known as Rimini. This city on the Adriatic coast was only 50 kilometers (~30 miles) from the Gothic capital of Ravenna.

Witiges could not tolerate this threat pointed at the heart of his kingdom. Before winter was over, he was forced to break up the siege of Rome and head back north. Taking the vast Gothic army with him, he immediately tried to revert the Byzantine success: Witiges laid siege to Ariminum.

The Byzantine expeditionary force was now awkwardly split between Rome and Ariminum. Although the capture of the latter had lifted the siege of the former, Belisarius’s situation actually looked worse than ever. To turn the tide, he now had to employ speed and deceit simultaneously.

The future of the Byzantine Empire in the west hinged on his next set of actions.

King Witiges once again built siege towers for a direct attack on Ariminum. Having learned his lesson at Rome, this time they weren’t pulled by oxen but by men stationed inside. However, the Byzantines inside of the city had some novel ideas of their own.

They charged through the city gates and quickly dug a deep trench across the towers’ trajectories. Responding to this development, Witiges ordered planks and other woodwork to be put over the gap and had his towers pushed forward. Unfortunately for the king, the timber collapsed under the weight of the towers. The siege engines were stuck in the mud. They would never see use again.

Having halted the Gothic advance halted once more, the Byzantine defenders of Ariminum had bought crucial time for relief forces to come to their rescue. Indeed, with his usual speed, Belisarius was rushing north to confront Witiges again. Still outnumbered by the army of the Goths, the general wanted to lift the siege of Ariminum by deception.

Upon reaching the besieged region, Belisarius actually split his force into four parts. One regiment was to move up the Adriatic coast by ship. The three others were ordered to light as many campfires at night as possible.

Assuming major Byzantine reinforcements had arrived, the sea of fires caused anxiousness in the Gothic camp. When dawn came the next morning, Witiges’s forces spotted Byzantine sails on the horizon. Although this was just one regiment, the Goths thought the imperial navy had arrived to lift their siege.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

Despite the fact that Witiges’s soldiers greatly outnumbered Belisarius’s army, complete panic ensued. The Goths fled from Ariminum. Emperor Justinian’s star general had taken Naples, Rome and Ariminum (Rimini) in two years.

Seemingly, the Roman cause was not yet lost. It has often been said that the Middle Ages started with the Fall of Rome. Obviously, the Justinian-Belisarius partnership made great strides to carry Antiquity forward into the 6th century.

In the end, the Gothic War that the Byzantines started continued for fifteen long years after the Siege of Ariminum. Both sides enjoyed their fair share of successes as well as great casualties. The Italian peninsula suffered considerably under the impact of this clash of cultures.

Afterward, the Byzantines managed to cling to control of Rome and Ariminum. But the cost of the conflict made sure that this was the end of Constantinople’s western ambitions. After emperor Justinian, the Eastern Roman Empire would firmly focus on the East.

For this reason, general Belisarius has been labeled as “the Last of the Romans”. He brought the ancient core and capital of the empire back under (Eastern) Roman control. Contemporaries of his campaigns would have laughed at the idea that Antiquity was supposed to be over.

On the contrary, under Justinian’s reign, the (Eastern) Roman Empire was alive and kicking. As it happened, it almost survived the entire Middle Ages, too.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Featured Image Credit: Fall3NAiRBoRnE (deviantART)

Comments are closed.

Thank you for that great article.

Thank you for reading, XMC. Glad you liked it!