MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Medieval life was controlled by two estates: the oratores - “those who pray” - held religious authority, while the bellatores - “those who fight” wielded political power. But these two orders were but a fraction of the general populace. The great majority of the European population belonged to the order of the laboratores, or “those who work”.

An extensive, and widely heterogeneous group, it comprised the economic engine of medieval Europe, evolving and growing through most of the period, remaining vital to the structure of the continent well into the Modern Age.

This is the third installment in our Three Estates saga, covering the laboratores. More interested in prelates and prayer? Then check out our first episode:

Are you interested in kings and knights instead? Take a look at our second episode:

If one were to conduct a census of any medieval kingdom or principality in Catholic Europe the demographics would show it was primarily rural. Even in the Late Middle Ages, at least two-thirds of the European population lived in villages sprinkled throughout the countryside, although sometimes near major towns and cities.

Countryfolk, as well as urban dwellers, were all part of the laboratores. A broad term for anyone who performed manual labor, it was at first a synonym for agrarian workers as a result of the economic environment. But over time, this societal estate came to include rich merchants, landowning freemen, and slaves. For simplicity’s sake, though, we will use the term “peasant” as a catch-all term for all rural laboratores.

Keeping with the supposedly divine ordering of the earthly world, it was any given laborator’s role to perform manual labor. In an era of little to no automation, this meant an immense range of tasks. In the beginning, most of them related to sustenance – farming and raising livestock for meat. As the Middle Ages progressed, however, the laboratores became fundamental in the expansion and growth of the medieval market economy.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

While slavery did exist in Catholic Europe, it mostly applied to non-Catholics, and in Catholic Europe at least wasn’t as widespread – although the Vikings and Magyars practiced it extensively before becoming Catholic kingdoms.

Medieval slavery didn’t quite match the notion of chattel slavery most associated with, for example, slavery in the United States. The latter was focused on cash crops and wholly reduced people to commodities not different from any other object, whereas early medieval slavery was meant for subsistence, where slaves worked the land in order to free others for other tasks. In fact, it was common even for monasteries and abbeys to have slaves! In other words, slavery mostly existed not by virtue of social class, but by social role.

There is still much debate about why slavery faded away in the Catholic world in the Middle Ages, but two main arguments are the top contenders:

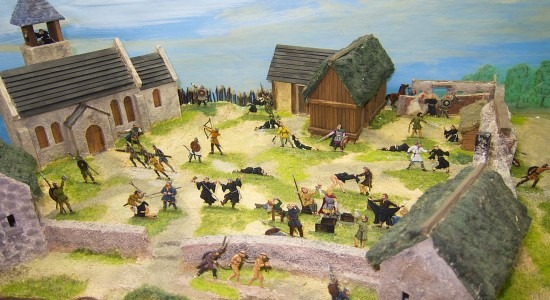

The Vikings, however, saw the value of slavery as an incredibly profitable market to be presented to the different Islamic polities all throughout the Mediterranean, and whenever plundering, took with them the occasional able-bodied person. Ireland, in particular, was the target of Viking slave raids. What the island lacked in circulating currency, it more than made up for in a well-nourished population, who had ample cattle and metallic wealth, such as chalices, plates, and reliquaries. While at first they only took the bullion and the occasional prisoner, the Vikings swiftly systematized the way they took slaves from Ireland.

We have the personal account of one such Irishman named Findan, in the mid-800s, to attest to this. He’d been sent by his father to negotiate the release of his sequestered sister, and after two close calls in captivity by other Vikings, from which he escaped, he was put on board a ship bound for Scandinavia. Slave markets existed there, usually connecting the western raiders with the eastern rivers that linked the Baltic Sea with the Black and Caspian seas, where slaves fetched good prices. Findan was lucky; his ship had a stopover in Orkney, northeast of modern-day Scotland. He fled, and to thank God, made a pilgrimage to Rome, ending his days as a monk in present-day Switzerland. It was not only economics that had driven his captors to take Findan so far away; forceful separation of a person from their community helped destroy their will, alas a desirable quality in a slave.

As Europe neared the second millennium, slavery was gradually replaced with serfdom, the former condemned by the Church in the 10th century and outlawed by various nobles in the 11th. Enforcing this, however, was difficult at best; we know, for instance, that despite having been criminalized by William of Normandy, slavery and slave trading persisted in England into the late 12th century.

Still, this only counted the treatment of fellow Catholics as slaves. Starting in the 12th century, Genoese merchants received special papal dispensations to sell slaves, provided these weren’t Catholic, to other non-Catholics. The business model they adopted was simple; they established themselves on the northern and eastern shores of the Black Sea, and purchased people wholesale, selling them in Acre and Alexandria. Slaves in the Mediterranean were often put to work in sugar and cotton plantations, as these are tremendously labor-intensive tasks that the manorial system in the rest of Europe couldn’t support. Baibars, who led a slave rebellion in Egypt, and ultimately established the Mamluk Sultanate, was a white-skinned man from the Caucasus.

To the modern observer, serfdom and slavery may seem almost interchangeable. Serfdom was a social institution whereby people were bound to the land they were born in. They were meant to work it for the benefit of the local lord, to whom all their possessions technically belonged. Serfs were subject to the lord’s law and could not leave the lord’s property without his permission first and had to pay fees to do so – which naturally limited options for marriage. When serfs inherited, they had to pay fees, usually in kind, to the lord. Even for mundane things (for medieval standards at least), such as brewing ale, serfs had to pay their lords, all-in-all making serfdom unappealing at best.

But then again, serfs were legally people in their fullest, limited as their rights were; in other words, the definition of slavery is dependent on the definition of a person – and serfs were, by all accounts, persons. Killing a serf was considered homicide (in contrast to Roman times, when killing a slave would have been the destruction of property), and serfs could buy their way towards freedom and petty landowning. In the later Middle Ages, as kings centralized power, a serf could theoretically present grievances against his or her lord before the lord’s superior, or the king himself – albeit the possibility of this happening was limited at best.

That is not to say that belonging to the laboratores was complete and constant oppression. While numbers are difficult to pinpoint, it is nowadays accepted that serfdom gradually declined from the 11th to 13th centuries. Towards the year 1300, little over half of the peasants in Catholic Europe were free in one way or another. Among those freemen, there were people anywhere from landowning peasants of their own right to wandering freemen who could travel from one estate to another looking for seasonal work.

Nowadays, we think of economic classes, stratified in a hierarchy founded on wealth. As we have seen, however, society in medieval Europe was rather defined by the role one took part in; wealth was usually a consequence of one’s role within the orders of society – and the two elites we have previously covered (link & link) usually took a bigger slice of the cake. Thus, the popular perception of the laboratores is that of peasants barely getting by, often covered in mud, and living in abject poverty – something the TV and film industries have promoted through the decades.

No mistake is to be made; the poorest among the laboratores did not escape far from said popular perception – usually serfs living in agriculturally unproductive areas, or perhaps under a particularly demanding lord. Above them, the average peasant, free or not, could sustain his life to a certain degree of security, weathering scarcity, and perhaps being able to afford the occasional luxury – a new tunic, imported alcohol and pottery, or proper cuts of meat. Atop them all were free landowners. All in all, these strata were not as rigid as one may imagine.

In fact, there were various opportunities for economic mobility for peasants within an estate. Chiefly, in plentiful years, landowners could sell their excess produce in nearby markets, and expand into further business ventures. These could naturally include buying nearby plots of land, animals, better tools, and even hiring landless workers for his own tenure. Landless freemen, on the other hand, could travel from estate to estate, hiring themselves to the best bidder - something that, after the Black Death, became ever more common: the workforce had shrunk significantly, and the greater number of freemen were thus free to negotiate better fares with the lords.

The cornerstone of medieval European economies was the manor. It was the smallest administrative unit in a fief, the land granted by a lord to his vassal, approximately a hundred hectares in size. Its purpose was to provide income to the ruling lord by exploitation of its resources, such as agricultural land, forests, streams, and mines. Within a manor, there may be one or many villages, small clusters of mud huts of varying quality where the peasants lived. The economic system based on manors has thus been named manorialism; it is, to economics, the analog of feudalism in politics.

While nearly all lords held manors, manors could be owned by institutions; Merton College, at Oxford University, owned a manor that provided the livelihood of the scholars living within. All throughout Europe, monasteries and abbeys owned manors as well which was one of the ways the Catholic Church owned land (between a fourth and a third of any given kingdom’s land), the other being direct ownership through a bishop.

Within the manor, there were two working subdivisions: the demesne, and the tenures. The demesne was the land to be exploited for the sole benefit of the lord. The tenures, on the other hand, were the lands where the peasants worked for themselves. The peasants owed tribute to the lord, and while they could provide it in kind, it was mostly in labor, known as corveé. Its payment was usually arranged on workdays; a peasant may work Mondays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays of the summer season in their own land, and the rest of the week (save for Sundays, naturally), on the demesne. Conversely, during harvests, the days may be inverted. Multiple manorial records from England attest to this scheme, which was widespread throughout Europe as well. Wealthy peasants could avoid doing the work themselves and send out a hired person in their stead - or, already in the 13th century, a cash sum equivalent to the cost of labor.

There was an ever-present concern, on the peasants’ side, that the lord may be too taxing, and impose unreasonable expectations on them. And while that happened at times, no intelligent lord would do that; modern studies have proven that there existed a correlation between the number of free landholders and overall wealth in any given region – not to mention that this promoted income equality, thus further boosting the local economy, transitioning it from a sustenance economy to a consumer-based one. Towards the 15th century, serfdom had all but disappeared in Western Europe, having mostly relocated to the vast plains of the East and it prevailed in various Slavic principalities well into the 19th century. It must be noted, though, that no lord was fully aware of the mechanisms behind this. Economics, as a science, still lay hundreds of years in the future.

Ultimately, the lord was concerned with how much money the manor could make for him, but by no means would he get his hands directly involved in the process. Therefore, the astute lord would delegate administration to locals. Moreover, the economic prosperity of a fief was a boon for everyone within, so a wise lord would take a generally hands-off approach to estate management – provided of course that the manor was profitable.

The head of the manorial administration was the steward, or seneschal. Usually an older and wealthier peasant, he oversaw the management of the lord’s lands for his gain, usually by making field visits to the workers. All his personal and professional expenditures were fully paid for by the lord he served, and in fact, the steward of a duke or baron could be a landed knight himself. Stewardship seems to have been a respectable profession, and there was even a famous manual, Seneschaucie, anonymously written in the 1270s for the purpose of standardizing instructions for stewards.

After the steward, there was the bailiff. Just like the steward, he would have come from the village on a meritocratic basis (as emphasized by Seneschaucie), and would have been literate, often receiving a decent salary, plus room and board in the lord’s stone-built manor house. For example, in 13th century Elton, in England, bailiffs were paid a pound a year, plus all living expenses, fodder for their horses, a fur coat a year, and money for their charitable donations on Christmas and Easter. The bailiff acted as an on-the-ground manager for the manor, for both technical and legal matters. He kept track of the manor’s inventory, from foodstuffs to tools, and prosecuted minor offenses when needed, although judgment would be passed by the lord.

The bailiff oversaw minor elected officers for the proper functioning of the manor, the foremost of them being the reeve. He was most likely illiterate, and received no payment at all, albeit generous lords would have him fed at the manor house. The reeve took care of concrete matters: he arranged the plowing teams, oversaw the upkeep of the manor’s infrastructure, and supervised the management of food and fodder, at times even sharing duties with the bailiff. He was exempt from the corveé, but the nature of the reeve’s duties meant he had less time for working his own tenure. Still, since the reeve was usually the youngest on the administrative scale; proving oneself in the role could mean advancing towards the positions of bailiff and even steward.

Much of the population in these villages was engaged in agriculture, one way or another – whether farming or rearing cattle. They often procured their own goods, whether it was pottery or clothes, but there was also a minority engaged in a few trades: smithing, baking, and milling. Both the latter would have done so in service of the manorial lord, who often owned the ovens and mills available, and (or if they weren’t his property) also collected a tax on it. Usually, this meant that an amount of the bread baked, or grain milled, would go to him; after all, the manor was for the lord’s profit, and profit he did.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

A minority of the people in the laboratores lived far from the farms, however. Whether within their walls, or right outside them, a fraction of the European populace lived in urban areas, its legal limits often defined by their physical boundaries – sizeable stone walls enclosing a privileged few of the laboratores.

In the 13th century, as had been the case for thousands of years, most large cities in Western Eurasia were around the Mediterranean Sea. Damascus, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Palermo, Valencia, Barcelona, Toledo, and, until 1204, Constantinople, were all cities of over 100,000 people. Elsewhere in Europe, most settlements didn’t exceed 50,000 people until the 14th century – Paris and London did so from the early 13th century. Still, throughout the High Middle Ages, there was a plethora of towns in the range of 5,000 to 25,000 permanent inhabitants, often swelled by fairs and pilgrimage. The biggest concentrations of these were in the Low Countries and Northern Italy, where urban density was the highest.

The term “burgher” originally came about to differentiate an urban member of the laboratores from their rural counterparts, its etymology stemming from the Germanic word “burgh”, meaning “fortress.” This referred to the walls that contained towns and cities, as villages were often unguarded – albeit in the proximity of the local lord’s castle. Later, during the High Middle Ages, “burgher” referred to the urban aristocracy, its status defined by the wealth acquired from craftsmanship or commerce – and from there stemmed the term bourgeoisie, to categorize these magnates that, despite their considerable economic power and social influence, lacked political authority because they were technically laboratores.

At any rate, in the 14th century, and especially in the aftermath of the Black Death, towns and cities pursued further independence from noble authority. In fact, this had been going on in the Holy Roman Empire since the 1180s; by the 13th century, a commercial alliance between the cities of Lübeck and Hamburg had expanded all through the Baltic and Northern Seas and secured rights for these settlements that made them practically independent. This “alliance” of towns and burghers was the Hanseatic League, and it stood in stark opposition to the traditional structures of landed nobility, rising to challenge their authority at times. The clash between town and country was such that, when the Scandinavian kingdoms restricted access to fisheries and sea lanes in the Danish straits in 1426, the Hanseatic League - this private, commercial cooperative made up of wealthy German burghers - went to war with them and won, proving that perhaps it doesn’t matter as much who allegedly holds power, but rather, who pays the most for it.

Comments are closed.

I?¦ll add you to my bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Hi, Birden! That’s amazing. You humble us. Thanks!

Magnificent website. Plenty of useful information here. Thanks for your effort!

Wow, Diaz. Thank you so much for your amazing feedback!

Nice post. I am impressed! Extremely useful information specifically the last part 🙂

Thank you and good luck.

That’s so kind of you, Lanvin! Thank you very much.

Thanks for writing this article. I enjoy the topic too.

You’re very much welcome, Kayleen. So do we! 😉

Thank you for posting such a wonderful article. I love the topic.

And thank you for reading it and commenting, Spencer. We’re grateful!