MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Running a medieval military order takes a lot of money. The Knights Hospitaller were quite proficient in raising cash from donations and from their wide estates. Still, they often ran into financial difficulties. Technological innovations greatly aided the Order’s economics, but also proved an enormous challenge when wielded by the Hospitallers’ ultimate late medieval enemy: the Ottoman Turks and their cannon.

In this third piece on Hospitaller history, we’ll focus on economics and technology as understood and employed by the Knights. This article is part of a larger series on the Order of the Knights Hospitaller that is largely historical but with a deliberately current perspective. Grab the other essays here:

The first episode covers the Order’s organization, structure, and diplomatic relations.

The second episode covers the Order’s healthcare practices as well as its medical legacy.

The Grand Masters of the Order were frequently concerned about their economic difficulties. The estates in the Crusader States of the Latin East could not sustain the Order by themselves. Furthermore, the value of donations was at times impacted by rampant currency depreciation and political upheaval throughout Europe.

The Hospitallers’ moral mission – to serve humanity’s needy – was so ambitious that the monetary needs of the Order were virtually unsatisfiable. The Knights owned many castles and estates, generating income through “land and stone”. Additionally, scores of noblemen bequeathed further grants to the Order, hoping to score points for the afterlife. The Hospitallers complemented these income streams with trade and the raiding of infidel lands. Still, all these cashflows were oftentimes insufficient to support the combination of the Order’s self-imposed ethos of charity and waging war against muslims across continents and spanning centuries.

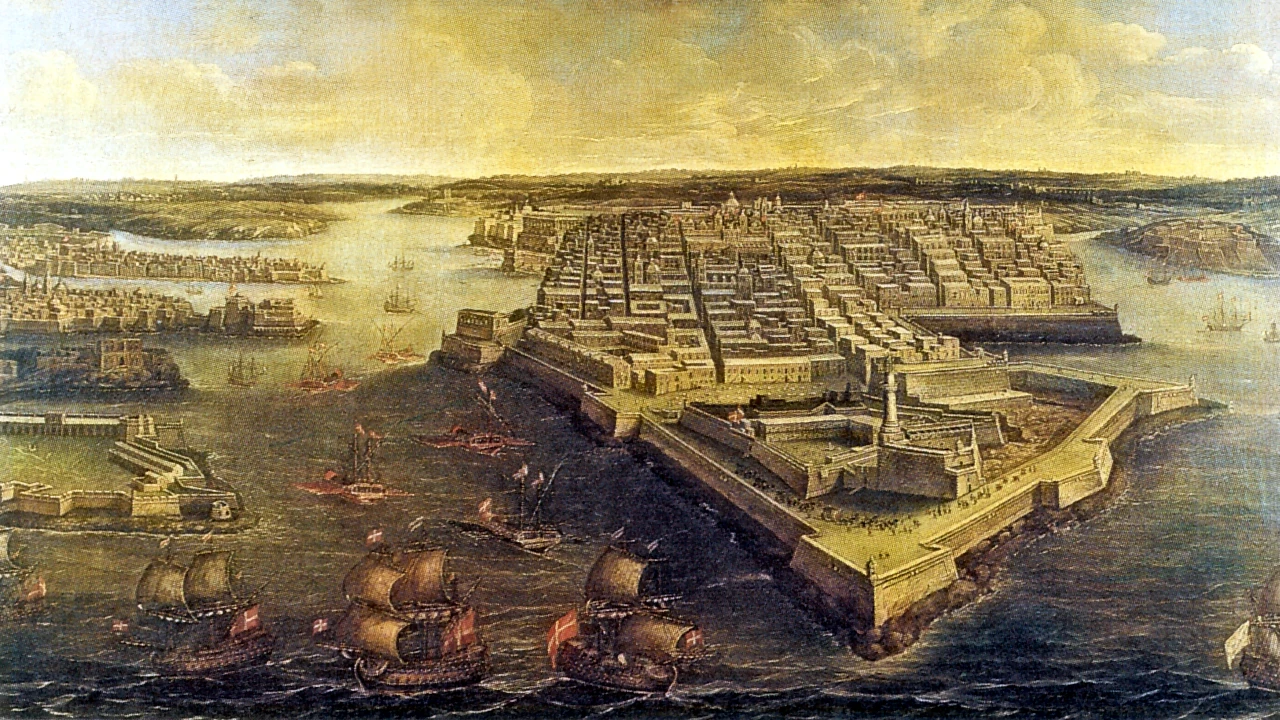

An academic from the University of Malta indeed calls the Knights Hospitaller “consistent frontliners on the Mediterranean’s ideological barricade”. To erect defenses, pay engineers and mercenaries, feed its islands and maintain its ships, Hospitaller HQ sought cash and supplies from the Western priories on a regular basis. The Order’s leadership, therefore, issued a large number of bulls asking that they send money, troops, and other resources to help Rhodes and the Hospitallers in the East to prepare for war.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –

It was beyond impressive that the Order was able to marshal resources from – in theory – as far away as Ireland. In practice, however, reliance on such far-flung territories also made the Knights Hospitaller vulnerable. These were the High Middle Ages, after all; without recourse to modern communication methods.

Local Hospitaller commanders could be corrupt, and priors sometimes accrued large debts – some of which were hard to justify. The results of harvests as well as the general state of the European economy was another factor that highly influenced Hospitaller revenues. On top of that, ships en route to Order HQ on Rhodes were frequently lost to the stormy Mediterranean.

One Cambridge historian even went as far as calling the reliance of the Knights Hospitaller on European estates “unhealthy”.

Many a Hospitaller chancellor spent his days worrying about the Order’s financial strains. When funds ran short, he had to take loans on a grand scale. For example, to be able to invade and conquer Rhodes in the first place, the Knights Hospitaller greatly indebted themselves to the papacy and Florentine bankers to finance the operation.

The profits from the Western priories were simply too sluggish or inconsistent to fully sponsor the continuous struggle for territory in the East – whether to wrest it from the forces of Islam, now concentrated by sultan Saladin and his successors, or to snatch it from Orthodox hands, as Rhodes had actually been Byzantine before.

The Knights also lived through periods of technical upheaval. The printing press was invented in the 15th century CE, at a period when the Ottoman (Turkish) threat to Rhodes was becoming increasingly severe. Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantines – fellow christians albeit Orthodox – fell in 1453 to the muslim Turks. This put the Hospitallers on Rhodes on high alert. The Turkish sultan would surely soon turn his eye to the Order’s island, they felt.

At the time, Johannes Gutenberg, a German blacksmith, pioneered a speedier and more efficient printing technique. Given the Hospitallers’ network organization, the reliance of the center on peripheral resources, the need to tighten communications, and the need for control to ensure the delivery of much-needed resources, the printing press’s communication revolution did not go unnoticed in Rhodes. The Knights indeed needed enhanced propaganda techniques as their epochal struggle against Islam seemed to be entering a new phase.

According to a Mediterranean historian from the University of Minnesota, the Order’s secretaries and its chancellor developed a narrative between 1453 and 1480 that consistently presented the Ottoman sultan as the enemy of the Knights of Rhodes. If their rhetoric was to be believed, the Ottomans dreamed day and night of conquering the Hospitaller island.

In 1480, the sultan did indeed launch a great offensive against the Knights Hospitaller. In a letter to the papacy, the Hospitaller Grand Master claimed the Ottomans had sent over 70,000 men against him that year. Although the number was probably exaggerated in order to extract further subsidies from the Holy Father, it’s beyond doubt that Ottomans launched a major offensive against Rhodes.

The Order’s clerks immediately used the Turkish onslaught to vindicate their decades-long warning call to christians in the West about the threat posed by the Ottomans.

After a shockingly fearsome bombardment by the Ottoman navy, the Turkish ground troops managed to enter the city of Rhodes itself. A bitter battle within the city’s walls ensued, with the Hospitaller Grandmaster allegedly participating in the melee in person. After hours of struggle and thousands dead, the Turks beat an unorderly retreat and lost thousands more.

Rhodes was safe again – for now.

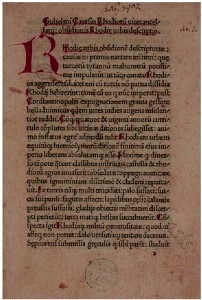

To mobilize increased support from the rest of the Hospitaller network, the Order’s chancellor published the Obsidionis Rhodie Urbis Descriptio only months later. It was a late medieval propaganda piece to raise men and money with which to withstand the other Ottoman attacks that were sure to follow. It included crucial rhetorical elements that traditionally guaranteed Western support and cooperation:

The Descriptio essentially built out the Order’s heroic character by offering a positive interpretation of the spirit and morale of the besieged christians on Rhodes. Additionally, it relayed the account of their victory over the heathens. In this way, the Descriptio aided the selling of indulgences to fund Rhodes’ defense against the Turks.

An official papal indulgence to raise money for Rhodes was printed only one year later and spread through Europe. A volume containing all the papal privileges ever granted to the Order was printed in 1495. Meanwhile, as research by a renowned Hospitaller historian shows, translations, adaptions and new editions of the Descriptio kept appearing.

The Hospitaller propaganda machine was completely fired up.

Wrapping us this three-part essay series on the Knights Hospitallers, historians and global affairs specialists look at today’s time of change on the international stage with uncertainty.

There is a recognition that the world order is transforming, on the back of or at least accelerated by – for example – the recent pandemic or the invasion of Ukraine. Both have uncovered vulnerabilities produced by globalization. Still, there is a lack of consensus and understanding as to where this change is headed.

Some argue that globalization has peaked, and we are advancing towards a de-globalization that would encompass fragmentation and regionalization. Governance models are put in question, and different world views are emerging. In this context, the Knights Hospitaller could represent a case study from the past to learn for the future.

Its network organization and distributed functioning were remarkably successful, considering the medieval technological means it could leverage. Its identity and jurisdiction system offered flexibility that was very versatile in a fragmented, feudal world. Its moral purpose did offer drive and incentives, whose dynamics might be of interest to a global society that – today – is seeking to recover meaning and belonging. Hospitaller challenges on the security, health and economic fronts were remarkably modern and showcase that little has changed, and we can still learn from the past if we want to.

In conclusion, the assessment of this study is that overall the Order acted as an incredibly resilient organization in a complex continent-spanning world order, regionalized and unstable, pursuing its mission and deploying skills and capabilities ranging from diplomacy to logistics to communications – all whilst managing resources from the edges of the christian world to deploy them against existential security threats.

– advertisement –

– article continues below –