MedievalReporter.com

Master the Middle Ages in mere minutes

Join our newsletter!

The latest on history's most marvelous millennium

The latest on history's most marvelous millennium

It was commonly known throughout the Middle Ages that Byzantine politics were dangerous waters to navigate. Many who entered the arena did not make it out alive. Emperor Justinian II, also, managed to have himself deposed but - although his bodily integrity was violated - carefully maneuvered himself back onto the throne.

The adventure cost him many years of his life and some body parts. His story, therefore, is not one of a stellar and altogether imperial career. Yet, his downfall and subsequent revenge probably make Justinian II the greatest political survivalist of Byzantine history.

Grab a short intro to the Byzantine Empire from our Medieval Guidebook.

Mutilating deposed emperors was probably the most brutal political practice in the Byzantine/Eastern Roman Empire. Accomplished through blinding, the cutting off of noses, ears, and limbs, and even castration in a few instances, mutilation served as a viable tool for an emperor or usurper attempting to sideline his rivals without resorting to execution.

While this practice can be considered overly cruel by modern standards, the Byzantines did have a religious rationale for mutilating ex-emperors; the Byzantine emperor was seen as the reflection of heavenly authority, which under God was supposed to be perfect and unblemished. Therefore, a mutilated emperor could no longer reflect this heavenly perfection and thus would be disqualified from holding the throne. These disqualified individuals would then be exiled, usually to a monastery, and were expected to play no further role in the politics of the empire.

However, there was one exception to this practice, an emperor who refused to accept his overthrow and exile, who broke tradition and retook the throne despite his mutilation. This is the story of Justinian II “The Slit-Nosed”, and his 10-year journey through the many kingdoms and cultures of early medieval Europe to reclaim his stolen crown.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Succeeding his father Constantine IV, Justinian II ascended the Byzantine throne in 685 CE at the young age of 16. His reign initially went well, as the young emperor scored early victories against the Arabs and Slavs raiding the imperial frontiers. The caliph, Abd al-Malik, even agreed to pay the Byzantines yearly tribute and share the income from Armenia, Iberia, and Cyprus - a much-needed victory after decades of defeat and territorial loss for the Byzantines. The pacified Slavs, meanwhile, were resettled in Anatolia to serve as a further buffer against Arab raids.

But Justinian II would soon squander his military successes with his less-than-successful domestic policies. Taxes were raised to unprecedented levels, earning the emperor the hatred of the Byzantine common folk. The recently subjugated Slavs were also incensed by this tax hike, with 20,000 of their number defecting to the Arabs and leaving the province of Armenia open to conquest.

Further exacerbating matters was the emperor’s own vindictive personality. Justinian II was an unforgiving man who never forgave nor forgot any perceived slight to his authority, and he responded to the crises affecting the empire with brutality. The Slavs still residing in Anatolia, many of whom had remained loyal to the Emperor, became the scapegoats for Justinian II’s military reversals, with thousands of innocent men, women, and children slaughtered under the orders of the vengeful emperor. Justinian II also doubled down on his harsh tax policies, dismissing any attempts by the Byzantine senate and aristocracy to alleviate this situation.

By 695 CE, after only 10 years on the throne, the emperor had thoroughly alienated both the military and the civilian population of the Byzantine Empire through his ill-advised domestic policies and military reversals. Leontios, a general in charge of the province of Hellas (Greece), took advantage of this wave of discontent by overthrowing the emperor in a successful coup. After first being paraded in chains throughout Constantinople, Justinian II then had his nose slit before being sent to exile to Cherson (in Crimea).

Leontios would rule the Byzantine Empire for only three years before military defeats against the Arabs led to his own overthrow by Tiberius III in 698 CE. Tiberius III, however, was no more successful than his predecessor, and his reign would see the remaining Byzantine territory in North Africa fall to the Arabs along with a failed invasion of Syria. These losses severely weakened his political position in the Empire, something that did not go unnoticed by a certain forgotten exile…

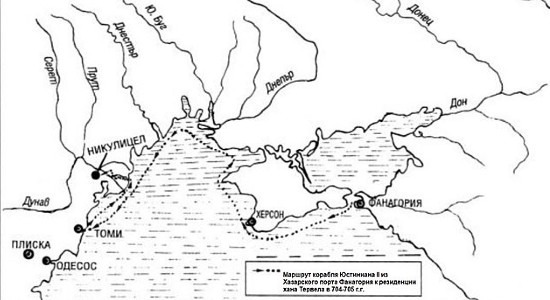

Upon learning of the precarious position the empire found itself in, Justinian II immediately began plotting his return to the throne. The city officials of Cherson, however, learned of his intentions and decided to capture and/or kill the ex-emperor before he could pose a threat to Tiberius. Justinian II then fled Cherson before the authorities could capture him, finding sanctuary in the court of Busir, khan of the Khazars.

Busir initially treated Justinian II with hospitality, with the khan even offering his daughter’s hand in marriage to the mutilated exile. In an attempt to connect with his namesake, Justinian II had her renamed Theodora, Justinian I’s famous empress.

In 703 CE, Tiberius III finally became aware of Justinian II’s escape from Cherson, and he gave Busir an ultimatum: either hand over Justinian II dead or alive, or the Byzantine-Khazar alliance would be considered defunct. Busir chose to betray his new brother-in-law rather than lose a valuable alliance, sending two Khazar officials to kill the man he had previously treated as a guest. But luck intervened once again on Justinian’s side as Theodora chose to warn her husband of her father’s intentions. When the two officials arrived to commit the deed, Justinian II personally strangled them before fleeing the Khazar khanate via a small fishing boat.

Justinian II then spent several weeks traveling along the northern coast of the Black Sea, briefly stopping at Cherson to gather his supporters while hoping to find further allies in the Bulgarian Empire. Near the mouth of the Dnieper River, his ship was caught in a storm. As the high winds and tumultuous waves threatened to capsize his vessel, the crew pleaded with Justinian II to pray to God for safe passage in exchange for showing mercy to his enemies in Constantinople. Reportedly, Justinian II’s response was:

“If I spare a single one of them, may God drown me here.”

— Out-of-office Justinian II commenting on his enemies in the capital

Even when facing death, the bitter Emperor refused to let go of his grievances.

Khan Tervel of the Bulgarian Empire welcomed Justinian II upon his arrival in Bulgaria, for he knew that the ex-Emperor would likely offer diplomatic concessions in exchange for Bulgarian support in a war of reconquest. In exchange for the hand of Justinian’s daughter, the title of Caesar, and various other gifts, Terval granted Justinian a large army of Slavs and Bulgars with which to capture Constantinople.

In 705 CE, nearly a decade of exile culminated in a siege of Constantinople by Justinian II and his supporters. Initial attempts to goad the citizenry to revolt ended in failure, with the ex-emperor receiving nothing but insults from the less-than-welcoming populace. Taking the city by force was also out of the question: Tiberius III had reinforced the famous Theodosian Walls, and any frontal assault would have broken against its near-impregnable foundations.

Fortunately for Justinian II, luck intervened in his favor one more time when the emperor discovered an unguarded aqueduct pipe, one that led directly into the city. Taking a few soldiers with him, Justinian II crawled through the aqueduct and gained entrance into the city, where he gathered his supporters and successfully captured Tiberius III before he could respond with a proper defense. The Siege of Constantinople of 705 CE had lasted a total of three days, with minimal casualties on both sides.

Having broken tradition and retaken his stolen throne, Justinian II wasted little time in enacting his long-awaited vengeance against his political enemies. Both Tiberius III and Leontius were found and dragged into the Hippodrome in chains, where the Emperor was waiting for them. There, in front of jeering crowds and sporting a newly-made golden nose, Justinian II placed his feet on the necks of his rivals in a ritual act of humiliation before ordering their beheading. The supporters of Tiberius and Leontius were also unable to escape the emperor’s wrath, and many were killed in the ensuing reign of terror. Even Callinicus, the patriarch of Constantinople, was blinded and sentenced to exile for his support of the two “usurper” emperors.

Justinian II’s reign of terror did not end there. The emperor had already exhibited some tyrannical tendencies during his first reign, and his mutilation and years of exile had not softened his heart. Now, he openly embraced tyranny, and his second reign from 705–711 CE would see the Empire purged of anyone he suspected of disloyalty. This included just about every capable officer in the Byzantine army, leading to further military reversals against the Arabs. Justinian II even turned against his benefactor, Khan Terval, leading an invasion of the Bulgarian Empire that ended in embarrassing defeat.

In 710 CE, Justinian II turned his vengeance towards Cherson, the Crimean city to where he had been exiled. A Byzantine fleet sacked the city, with Justinian II personally roasting seven of its greatest nobles by tying them to spits over fires. On its way home, the fleet sank in a storm, but Justinian II survived and was even said to have laughed at the news of its destruction.

Sacking one of the Empire’s own cities proved to be the breaking point for the Byzantine army, and they rebelled under a general named Philippicus Bardanes. When the emperor sent a fleet to quash the rebellion, they defected to the rebels and immediately sailed back to Constantinople. Justinian II initially escaped capture and fled to Damascus, but this time his luck had finally run out. The emperor was captured by Philippicus’ forces on November 4th, 711 CE, and he was executed to ensure that there would be no third chance for the “Slit-Nosed” to return to power. His six-year-old son, Tiberius, was also tracked down and killed, putting an end to the Heraclian dynasty that had ruled the Byzantine Empire since 610 CE.

Justinian II remains one of the most interesting figures in early Byzantine history. His overthrow and eventual comeback is an impressive story, and he deserves some praise for his sheer determination and refusal to accept the fate given to him. But as amazing as his comeback may be, Justinian II was also a cruel and unforgiving man primarily motivated by vengeance, and thousands of innocents would perish as a result of his tyranny. Through these weaknesses in character, all of his achievements were undone in a matter of years, and he would die alone after his empire had turned against him - twice.

The death of Justinian II would mark the beginning of a period of anarchy for the Byzantine Empire, as new emperors rose and fell in rapid succession while Arab raiders drew ever closer to the walls of Constantinople. It would only be during the ascension of emperor Leo III in 717 CE and the defeat of the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople that the Byzantine Empire would experience some form of stability again.

This article was the winning contender of our Medieval Writing Challenge of 2022.

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay informed of future contests!

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports, guides and reviews. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning - at no additional cost to you - we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Featured Image Credit: Simulyaton (deviantART)