MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The Magyars, by now better known as Hungarians, were in many ways one of a kind. Originally steppe people from Siberia, they condensed into a firm kingdom near the heart of Europe. There, they acted as both buffer between and bridge to the major medieval power blocks back then:

The Magyars thus surrounded themselves with both opportunities and threats by striking so deep into the continental interior. On account of their Asiatic roots, all their neighbors were also culturally as well as linguistically unrelated to the Magyar people. Their adopted home in the Pannonian Basin (where they still live), proved to be a bulwark to their uniqueness but was simultaneously a focal point of hostile military expeditions.

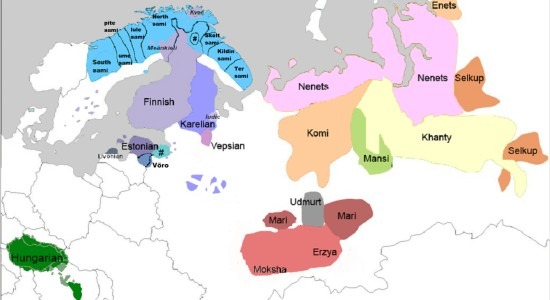

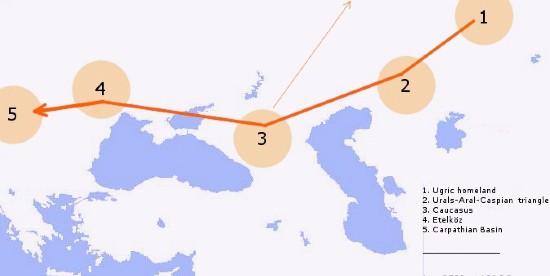

The Magyars probably came from forests west of the Ural Mountains in modern Russia, according to linguists and archeologists. There, they separated from peoples who would eventually settle Finland and Estonia about two millennia ago. These Finno-Ugric roots, as their language family is called, set the Magyars apart: they were neither Slavs nor Huns. Apparently, the Magyars then roamed southwards until they settled in the steppes between the Black and Caspian seas. They spent centuries in these seemingly unending plains.

On the eastern flanks of this Pontic-Caspian steppe, Turkic confederations expanded their influence and thus made enemies. The Magyars fought hard against them but also incorporated many Turkic features, such as their social organization and many words and terms referring to equestrian and military activities. Nevertheless, the Turkic pressure eventually became to much to bear and the Magyars moved west.

They relocated directly east of the Carpathian Mountains, in present-day Western Ukraine. To strengthen their steppe distinctiveness, the Magyars incorporated a tribe from the equally nomadic Khazar confederation. In the meantime, they directed their military attention to the Byzantine Empire and the Rus’ principalities. The Magyars spent the better part of the 9th century CE harassing both. But the Turks were still chasing the Magyar’s tail.

The Turkic Pechenegs swept all the way through the Pontic-Caspian steppe, driving the Magyars west once more. They made contact with Western Europe, where they were first mentioned in writing in 862. By the end of the 9th century, the Magyar migration had taken on the form of a full invasion. With the Turks hot on their heels, the Magyars made quick work of conquering the Pannonian Basin. They subdued the Slavic peoples living there and expelled to the east the Wallachians.

On the vast Pannonian plain, the Magyars could exploit their steppe tactics. The landscape was suited to their style of warfare. Additionally, the Carpathian mountain range to the east shielded them from attacks by other steppe people. After a flight of centuries, the Magyars were finally safe from Turkic assaults. However, having injected themselves into the heart of Europe, they now had to make do with all kinds of new neighbors.

The powers surrounding the Magyars were not universally friendly to them, not in the least because the invaders had spared no church or monastery during their conquest. Before long, the Magyars were warring against German principalities to their west, the Kingdom of Moravia in the north, and the Byzantine sphere of influence to their south. The hit-and-run style of combat that the Magyars brought with them from the steppe was initially devastating. But as the 10th century progressed, the European nobility learned how to fight against the lightly armored Magyar horsemen. In 955, the king of Germany - future emperor Otto I - annihilated the eastern invaders by relying on heavy cavalry.

Afterward, Magyar raids declined substantially.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

The Magyars have always been “Hungarians”. In fact, to this very day, the Hungarians call themselves Magyar - the terms are interchangeable. The naming issues related to this civilization caused confusion in the Middle Ages, too. The Byzantines and muslims simply called them Turks or even “Dacians”. The Slavs called them “Ongri”, of which the ultimately popular term Hungarians is a derivative.

Naming issues aside, the Magyars left a deep imprint on European medieval history. They became Catholic in the year 1000, when they also founded the Kingdom of Hungary. It would last nearly a millennium. The Kings of Hungary kept fighting the Holy Roman Emperor. They also expanded their influence into Croatia.

During the High Middle Ages, not even the Carpathians could prevent the nightmare of the Hungarians from continuing. Once again, they were attacked by steppe people from the east. First, the Cumans invaded; then the Mongols rushed west. The Hungarian king even invited Teutonic Knights to protect his eastern border, but it was to no avail: the Mongols duly destroyed the Hungarian army. Fortunately for the Magyars, the Mongol menace disappeared as soon as it had arrived.

This allowed the Kingdom of Hungary to crawl back up during the Late Middle Ages.

Signifying their transition from exotic invaders to full participants of European power politics, the Hungarians became ensnared in dynastic struggles. The French House of Anjou laid claim to the title King of Hungary. Through a civil war, it managed to drive out the native Hungarian dynasty. To complicate matters, the Angevin kings also controlled the Polish crown for a while and intermarried with the Holy Roman Emperor’s family. When Hungarian king Louis of Anjou died in 1382, his son-in-law - the emperor - succeeded him.

In 1458, the Hungarians had enough of this foreign “occupation” and installed the native Matthias Corvinus on the throne. Inspired by the writings of Julius Caesar himself, he built a professional standing army. On account of its attire, it was called the Black Army. It was far larger than the army of France, the only other permanent military force in Europe at the time. With his Black Army, Matthias Corvinus scored great victories against the Turks, who had just conquered the Byzantine capital and seemed intent on reigniting their epochal struggle with the Magyars.

At the Battle of Breadfield, in current-day Romania, the Hungarians inflicted a stinging defeat on the Ottomans. With his death in 1490, however, the Hungarian war effort fell apart. At Mohács, in 1526, the Ottoman sultan had his revenge: he annihilated the Hungarians and their king drowned in a creek during the escape. Central authority collapsed after that, as Hungary was ground down between the imperial ambitions of the Ottomans and the Holy Roman Emperor throughout the Early Modern Era.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Grab a short intro on another civilization from our Medieval Guidebook.