MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Ah, the Romans. Who doesn’t want to be like them? Ever since the legions conquered an empire from the border of Scotland to the deserts of Arabia, many European empires have tried to imitate, claim or even continue Rome’s legacy.

From the First French Empire under Napoleon to Fascist Italy in the 20th century, and ranging from the claims of the Ottoman Portes to the Russian Romanovs, strings of sultans, czars and monarchs have asserted themselves as a continuation of the Roman emperors of old. Throughout European and Mediterranean history, anybody with even a modicum of ambition seemed to trace either his personal lineage or the roots of his realm back to that great empire of Antiquity.

This became a pesty problem, particularly during the Middle Ages, when the western and eastern halves of the Mediterranean drifted apart culturally and politically. You see, although the Eastern Roman Empire was still around, emperor included, the insolent Franks had their king Charlemagne crowned as Roman Emperor, too!

This was, in short, the Two-Emperors Problem: who was the real Roman emperor?

Grab a 5-minute intro to the Franks and the Frankish Empire from our Medieval Guidebook.

Grab a 5-minute intro to the Eastern Romans (or Byzantines) from our Medieval Guidebook.

The end of civilization, on closer inspection, is never nigh. Adrian Goldsworthy, British historian and an authority on the Romans, explains in his masterpiece How Rome Fell that - basically - it didn’t. The last Emperor in the West, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed on September 4th, 476 CE, but nobody woke up on September 5th to proclaim that Classical Antiquity had ended and that the Middle Ages were upon us.

As it happened, during the Later Roman Empire, the one army that could beat the Romans in a protracted conflict was the Roman army itself.

This is not to say that the Western Empire was not terminally ill during the 5th century CE. Infighting and civil war remained a Roman concern throughout most of this period. But the Roman army was still the most effective fighting force on the planet, fielding hundreds of thousands of soldiers, capable of achieving at least a stalemate in longer conflicts against any competitor as long as high command was unified.

And it’s precisely here, at the imperial top of the pyramid, that - despite (tactical) victories or “draws” against Alemanni (378), Picts (398), Persians (422), Huns (451), Alans (464), and so forth - our emperor problem presents itself.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

On paper, the Roman Emperor was basically god on earth. The office brought nearly unlimited political power (save some dealings with the Senate), religious authority beyond measure (the “imperial cult”), and ultimate command over probably the largest army in the world. However, problems started to appear as soon as this army realized its own importance: in a military dictatorship, the military is as powerful as the dictator and vice versa.

Coups against the emperor already occurred in the first century CE, but the awful Crisis of the Third Century made painfully clear that anybody able to round up the legions could become emperor. Later emperors learned from this horrific epoch by keeping their best troops in reserve near the capital, lest a usurper rise up from their ranks. (This, amongst other things, led to several defeats against the “barbarians” as the armies protecting the borders were deprived of most elite units.)

The Crisis of the Third Century also led to another momentous decision: the Empire had proven to be too large to govern. Any emperor wishing to campaign in the East to finally inflict the death blow against the pesky Persian Empire risked revolts in Britannia, Gallia and Hispania for the simple reason that he was absent. So, from 395 onwards, the Empire had two courts, two capitals (Constantinople and - most of the time - either Milan or Ravenna), and more importantly: two emperors.

This move in itself was pretty paradoxical. The office of emperor implied rulership not just over the Roman Empire, but - theoretically speaking - over the entire world. Imperial Rome was, indeed, a universal monarchy; only the Persians were viewed as somewhat equal - or at the very least, “not barbarian”. (When the Romans learned of the existence of China and its emperor, this worldview proved inadequate but the Chinese were so far away that it was of little consequence.)

For the Romans, however, the arrangement made perfect practical sense. They prided themselves on the fact that their empire was so large that it took more than one emperor to rule it. Indeed, government took great care to present the two rulers as co-emperors and as an “imperial college”, looking after the Roman state together. The border between the Western and Eastern Roman Empires was practical and porous, like how a kingdom may arrange its territory into provinces. In fact, the two empires co-governed what they called patrimonium indivisum - an “indivisible (e)state”.

So what happened when the Last Emperor of the West, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed in 476 CE? For ages, Western historians have depicted this moment as “the Fall of Rome”, “the end of classical civilization”, or - even worse - “the dawn of the Dark Ages“. For the Eastern Roman Emperors, however, this provided a golden opportunity.

Although Roman state propaganda had gone to great lengths during the 5th century to position the Western and Eastern Roman Empire as one state, it was undeniable that they had grown rather apart by 476. Romulus Augustulus was not even officially recognized by the Eastern Roman Emperors residing in Constantinople. In official terms, his deposition didn’t mean anything bad.

In the event, the court at Constantinople decided to jump at the opportunity. It reintroduced universal monarchy pur sang. When the (possibly Gothic) warlord Odoacer had deposed Romulus Augustulus, he requested the Eastern Roman Empire to send him the imperial regalia so that he could reign as Emperor of the West.

Constantinople refused, stating that the West no longer required a separate emperor and that “one monarch sufficed [to rule] the world”. A purer expression of universal monarchy is hard to come by. Odoacer was named dux Italiae (“duke” of Italy) by the Eastern Emperor, who was now - once again - sole sovereign on earth according to Roman propaganda.

If anything, the “Fall” of Rome was somewhat of an upgrade for the Eastern Roman emperors. Rather than having a co-ruler in the West, who had grown into a bit of a competitor, they now had a barbarian vassal in Italy that they could order about. And order about they did.

When Odoacer grew unruly, the Ostrogoths under the leadership of Theodoric were hammering the Balkan provinces of the Eastern Roman Empire. In typical “divide and conquer” fashion, always a hallmark of Greco-Roman foreign policy, Constantinople now sent Theodoric against Odoacer with the promise that he could take over Italy. The Ostrogoths summarily defeated Odoacer and Theodoric invited his opponent to a supposed reconciliation dinner but had Odoacer killed at the feast instead.

Theodoric, however, was unsatisfied with the position of dux Italiae. Constantinople, too, was divided on how to proceed. One faction at court wanted to make further use of the Ostrogoths and send them against other “barbarians” as well; another party did not want to aggrandize Theodoric out of fear that the Ostrogothic leader might proclaim himself Augustulus’ successor - and thereby resurrect the Two-Emperors Problem!

In the end, the Eastern Roman emperor did send Theodoric the imperial regalia (an honor that Odoacer had been refused) and lifted him up to the title of rex - “king”. Theodoric, for his part, kept his position purposefully vague as well. On the one hand, he dressed in purple, an imperial prerogative, and allowed his subjects to call him augustus, which basically meant “emperor” by then; on the other hand, he minted coinage as rex, never quite specifying what he was king of, and stated that “an[y] able Goth wants to be like a Roman”.

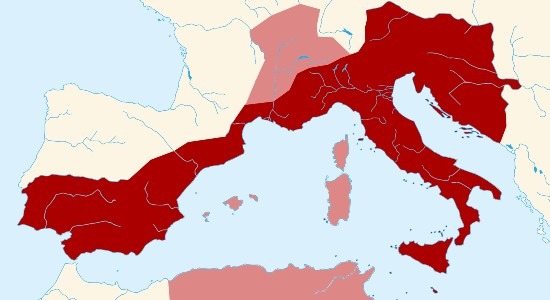

Over the following decades, Theodoric conquered so much territory from the Burgundians, Franks and Visigoths that he restored much of the “fallen” Western Roman Empire without the emperor of Constantinople having to lift a finger; indeed, some early medieval historians view Theodoric rather than Romulus Augustulus as the last Roman emperor in the West.

In 518 CE, the Justinian dynasty took over the Eastern Roman Empire. Theodoric was at the height of his power - by now called “the Great” - and had proved himself a loyal and useful subject of the Empire. For the Justinians, this was not enough: they belonged to the universal monarchy faction and wanted complete submission from the Goths.

No “rex in the West” could exist under their rule; on the contrary, this dynasty launched a program of renovatio imperii (“restoration of the empire”), a concept that would prove popular with the later Frankish and Holy Roman Emperors as well. Especially emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565) tried to resubmit the Ostrogtohs to his imperial authority.

He launched a decades-long invasion of Italy, the Gothic War. At great financial and humanitarian cost (combined with what was arguably the worst year in living history), Justinian reconquered the Italian peninsula and broke the back of the Ostrogothic kingdom. The victory, however, proved hollow: the conflict not only devastated Italy itself, but also depleted the imperial treasury and army.

Within decades, other “barbarians” invaded: the Lombards. They gradually conquered most of Italy, with Constantinople ultimately unable to resist their advance. To make matters worse, the Lombards refused to accept suzerainty to the emperor. By trying to remove the King in the West (Theodoric), the imperial court had managed to dismember the West entirely: the somewhat malleable Goths were now replaced by the headstrong Lombards.

Regarding the Two-Emperors Problem, though, there was a silver lining to be found here. Never did the Lombard kings imply that they were of imperial rank, so at least for propaganda’s sake, the Eastern Emperor could still present himself as sole sovereign on God’s earth. However, during the 8th century CE, this would all change as the ambitions of the Franks grew to universal proportions.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

The earliest Frankish monarchs had actually accepted the emperor as their suzerain, at least in a nominal sense. But inspired by the achievements of Theodoric the Great, and capitalizing on a period of Roman weakness during the Gothic War, the Franks soon stopped doing that. Already before 550 CE, Frankish king Theudebert struck coins in his own image - rather than in the emperor’s - and, in a game of one-upmanship with the late Theodoric, not only styled himself rex but even rex magnus (“great king”).

This was an insult directed at Constantinople, but with the Lombards now nested in Italy - between the emperor and the Franks - there was little he could do about it. Fortunately for the imperial court, this was as bad as it got for two centuries. From 750, though, things went from bad to worse.

In 751, the Lombards finally conquered Ravenna, which had been the nexus of Roman administration for centuries by then. Pre-occupied with beating back the advance of Islam, both in the Middle East and North Africa, Italy was left to fend for itself. The pope, who was formally a vassal to the Roman emperor in Constantinople, started looking elsewhere for protection against the Lombards.

A new ally presented itself in the form of the Franks: the pope called them to their rescue. From 768, it just so happened that they were ruled by one king Charles, who would also go on to be called “the Great” or, more popularly, Charlemagne. The Franks happily invaded Italy and defeated the Lombards, annexing their kingdom.

Both Charles and the pope looked for opportunities to consolidate the situation further in their favor. To their luck, the perfect storm broke loose in 797. In Constantinople, Irene of Athens, mother of child-emperor Constantine VI, had her son captured, blinded and deposed.

Then she did something unheard of in over 1,500 years of Roman history: Irene, a woman, became emperor herself and ruled in her own right.

As women were widely thought to be unfit to rule at the time, making empress Irene’s rule illegitimate, king Charles and pope Leo exploited the political crisis as best they could. On Christmas Day, 800 CE, the king of the Franks was crowned imperator Romanorum (“emperor of the Romans”) and became Charlemagne that very day. He had coins struck that styled him imperator augustus Romanum gubernans imperium (“August Emperor, governing the Roman Empire”).

These titles were important in the sense that Charlemagne specifically did not have himself crowned as “Emperor in the West”. He was not the successor, legally speaking, of Romulus Augustulus or Theodoric the Great. Charles was now officially Roman Emperor, succeeding the illegally deposed Constantine VI and officially denying empress Irene’s claim to the title.

According to Frankish propaganda, Charlemagne was the sole legitimate monarch in the world. Rather than the classical co-government by East and West (the consortium imperii), this turned into a new, medieval system where the Franks claimed that power had moved from East to West (the translatio imperii). In other words, the Two-Emperors Problem was back, and it was even worse than before.

Interestingly, the two courts - in Aachen and Constantinople - rapidly responded to the situation. The Franks had introduced a revolutionary paradigm that required a new way of looking at things. It would change the rest of the Middle Ages forever.

We break down the impact of this bold move by Charlemagne and his Saxon successors, the first Holy Roman Emperors, in another report: episode #2 of the Two-Emperors Problem.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports, reviews and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning - at no additional cost to you - we will earn a small compensation if you click through.