The sinews of war are infinite money, so the Hospitallers basically never had enough. Propaganda, then, was a useful means to increase their income.

Read moreHospitaller History (3): Finances, Technology & Propaganda

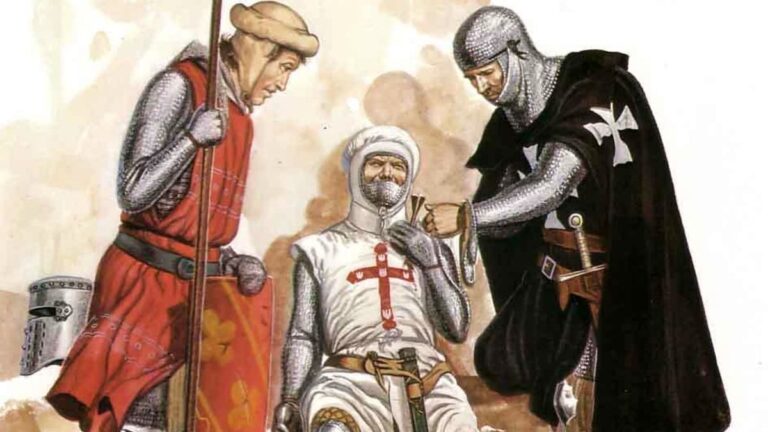

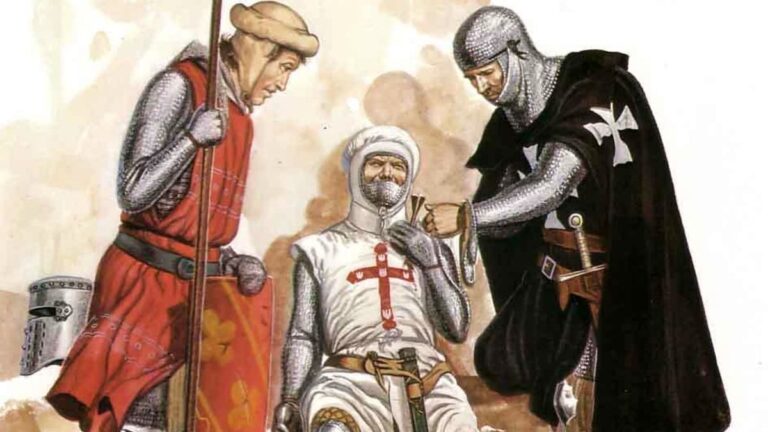

Tending to the sick was quintessential to the Order of the Hospital, but how did Hospitaller healthcare actually work in an age before modern medicine?

Read moreHospitaller History (2): The Knights as Medics and Doctors

The Knights Hospitaller started with an infirmary in Jerusalem but soon formed an extensive network throughout medieval Europe, comparable to a modern NGO.

Read moreHospitaller History (1): An International NGO in the Middle Ages

Both the Holy Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire claimed to be the true "Roman Empire". Which state best claimed Rome's legacy?

Read moreThe Two-Emperors Problem (2): Byzantine Basileus vs. Holy “Roman” Emperor

How did the Roman Empire lose the West? Learn about upstart Goths, disloyal Lombard and insolent Franks - all working with and against a court in Constantinople that was waging war on many, many fronts.

Read moreThe Two-Emperors Problem (1): Will The Real Roman Emperor Please Stand Up?

When a fully-fledged Timurid army swoops into India with tens of thousands of horsemen and camels, only to be met with armored war elephants, death and devastation are sure to follow.

Read moreDelhi Devastated: How Timur Crushed India’s Capital