MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

He went on crusade five times. He could count among his allies the King of England, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, and several Holy Roman Emperors. On top of that, he fought Moorish pirates in North Africa and was the first man on the continent to receive the Order of the Garter.

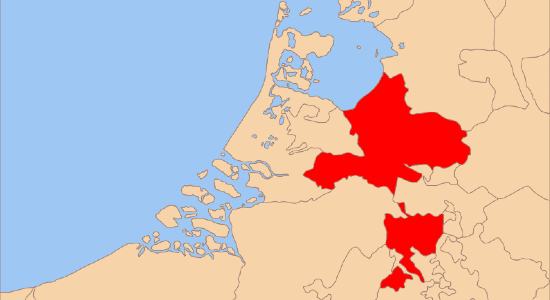

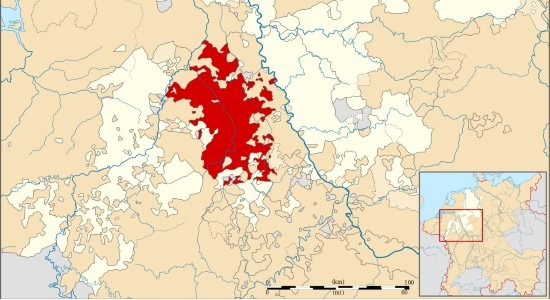

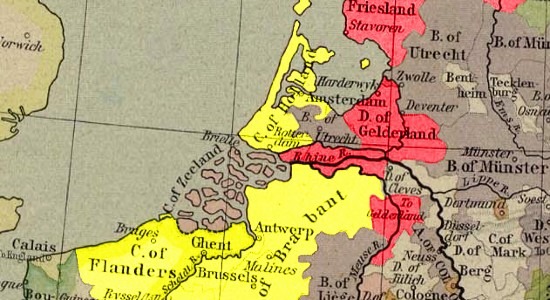

His name was William. He was the dashing duke of Guelders (where he was known as William I) and Jülich (where he reigned as William III). Both duchies were in the west of the Holy Roman Empire, the former now being a Dutch province and the latter a town in the North Rhine-Westphalia state of Germany.

In an age where chivalry was idealized, William became known as the perfect knight. He hosted many tournaments and tried to be the embodiment of the crusading spirit. The duke was a downright celebrity in medieval Europe.

Grab a short intro to the Teutonic Order from our Medieval Guidebook.

William sported two ducal titles (Guelders and Jülich) later in life. But, as the eldest son of the duke of Jülich, he was born as heir to only of them. He obtained the duchy of Guelders thanks to a peculiar turn of events.

William’s mother was Maria of Guelders and, as a woman, not really in the line of succession to the duchy. Meanwhile, her brothers - William’s uncles - disputed each other’s rights to rule Guelders. In 1361 CE, a few years before William was born, one uncle triumphed over the other and imprisoned his opponent.

All this was rather irrelevant to Maria’s position and the Duchy of Jülich, but the uncle in charge of Guelders soon started messing things up. He got into a war with the neighboring Duchy of Brabant. And although he was quite successful on the battlefield, he ultimately got hit by an arrow and died in 1377.

William’s other uncle was quickly released from prison to rule Guelders once again. But having languished in the dungeons for over fifteen years, he was in poor health. He reigned over the duchy for three months and then died as well.

All of a sudden, William was the last male representative of the Guelders bloodline. Therefore, at age seven, the Holy Roman Emperor formally awarded him the duchy. On account of his age, his father - the Duke of Jülich - ruled it in his stead until William was grown up.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

In the Middle Ages, children assumed adult responsibilities at a much younger age than nowadays. So, when William was only thirteen years old, he was considered mature enough to rule in his own stead. In 1377, he took control over the Duchy in Guelders - with his father still alive, Jülich would have to wait.

It took him two years to completely subdue the duchy. His claim was contested by nobles from the Veluwe and Betuwe regions. They argued that his mother’s sister - William’s aunt - was better suited to carry on the line of succession.

But, with the emperor’s blessing and the support of major cities like Arnhem and Nijmegen, William soon got the upper hand. He managed to stamp out the smoldering conflict, which had raged across the duchy since his childhood as the “First War of the Guelderian Succession”. In 1379, his rule was safe and secure.

The era William lived in highly prized chivalric splendor. With nothing to fight against for the moment, William of Guelders decided to host a string of jousting tournaments. Not only did this allow his noblemen to hone their skills; it also channeled the rivalry of the nobles he just subjugated into something more sportslike.

Under William’s reign, life at the Guelders court was celebrated throughout Western Europe. To add to his majesty, the duke added several famous physicians, barbers, musicians and falconers to his retinue. But most important of all were the cooks, who prepared lavish banquets and even hosted cooking contests.

The courtly life could only entertain young William for so long, though. Before he was twenty years old, he dreamed of the highest knightly virtue of all: to go on a crusade.

The crusader ideal was very much alive in late medieval Europe, despite the fact that the Holy Land had long since reverted to muslim control. The narrative of the Crusades had changed in the meantime. Liberating Jerusalem was no longer an explicit objective.

Instead, pagans and heretics across Europe were the new targets, as well as Moorish Iberia. Emblematic of this new crusading spirit were the Teutonic Knights. At the time, they weren’t even active in the Middle East anymore, having shifted their focus to Eastern Europe.

In this theater of war, the Teutonic Order organized yearly Reisen. The word literally means “journeys” in German but actually meant the seasonal campaigns of the Teutonic Knights against the pagan Prussians, Lithuanians, and other Baltic tribes.

These Prussian Crusades, as they were called, were the perfect excursions for young European noblemen, looking for glory on the battlefield without wanting to formally declare war on one’s (christian) neighbor. The Reisen were exactly what ambitious William of Guelders had been looking for: in 1383, at age nineteen, he signed up for his first crusade.

He traveled across the Holy Roman Empire and joined the Teutonic Knights in the Baltic. William soon found out he enormously enjoyed crusading. He was good at it, too. Additionally, the crusade added enormously to his already famous prestige and he befriended many members of the Teutonic Order.

As soon as he got home from his campaign, he made preparations to go again. But upon his return, local politics deterred him from doing so. William felt mightily frustrated by these developments, yet the event actually made him a downright celebrity throughout Europe.

Whilst William was campaigning in the East, the Hundred Years’ War engulfed much of Western Europe. It was formally a war between France and England but sucked in neighboring duchies at breathtaking speed - most notably Brittany, Burgundy, and Brabant.

In the event, the enmity between Guelders and Brabant was still strong. Recall how William’s uncle had found his demise while fighting the neighboring duchy. Against the backdrop of the Hundred Years’ War, Brabant became increasingly associated with the French camp.

Consequently, William of Guelders allied ever more closely with the English. Conflict was brewing between the two duchies, as the Hundred Years’ War threatened to spill over into the Holy Roman Empire. Before William could depart on another Reise, war broke out.

Brabant quickly found out what the Teutonic Order had already noticed: William of Guelders was quite the capable commander. He campaigned successfully in the Duchy of Brabant for two years. Driven to desperation, his opponents called in the help of their mightiest ally: the King of France.

The French immediately marched north, determined to nip this fresh front in the bud. The king arrived in Brabant, allegedly with 100,000 soldiers. This was way too much to handle for the army of Guelders, so William retreated and formally apologized.

The King of France - who had a lot on his mind, not in the least war with England - accepted and didn’t press the issue any further. Militarily speaking, the war with Brabant ultimately didn’t bring William much. But his stance against France made him famous among the European nobility.

With the Brabant war behind him, William immediately took to crusading again. As his army was already assembled, he took his troops eastward. His second crusade had been long coming; finally, he could rejoin the war in the Baltic.

However, the political situation in the area had changed significantly since his last Reise. By the marriage of their heads of state, the Poles and the Lithuanians had entered into a personal union. The alliance had the implicit goal of checking the Teutonic Order’s advances in the region.

Faced with an adversary threatening to eclipse them, the Teutonic Knights began applying pressure on smaller states, compelling them to choose sides. Small counties and duchies along the Baltic littoral were thus forced to pick between the Order or Poland-Lithuania. Because William of Guelders had closely associated himself with the Teutonic Knights on his first Reise, he was treading on dangerous ground.

Before he could even cross into Poland proper, a duke in the east of the Holy Roman Empire tried to impress his Polish allies and apprehended William. For months, the duke of Guelders was imprisoned in a castle - not exactly how he had pictured his second expedition to the East. Finally, after half a year, the Teutonic Grand Master himself negotiated his release.

His honor offended, William demanded a formal declaration of his freedom from the duke that had taken him prisoner. Fearful for loss of face in front of his retinue, this duke alone then climbed a tree near an isolated river deep in the woods. He shouted his declaration from the canopy, with only William and a couple of Teutonic Knights on the river’s other side to hear it.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

With almost the entire campaign season spent already, William broke off his Reise then and there and returned home. He was annoyed by the political instability in the Baltic region. His second campaign had turned out to be a major waste of time and resources.

William decided that he had to leave his Teutonic allies hanging for the moment and started working on other ways to increase his prestige. He went to England to make new friends and visit old ones. The trip turned out to be well worth his time.

King Richard II was thankful for William’s defiance of the French in the war against Brabant. So he made the duke of Guelders an official knight of the prestigious Order of the Garter, established by Richard’s grandfather - king Edward III. William was the first nobleman from the continent to be honored in this way.

Reinvigorated by this august award, he began planning new crusader missions. But before he went east again, something else needed to be done. William set sail to Jerusalem to pray for God’s blessing on future expeditions.

On his way back from the Holy Land, the duke found a temporary crusader side hustle in the Mediterranean. His zeal rekindled, he joined a European fleet fighting the Moorish pirates of North Africa. No matter where he went, the duke of Guelders found opportunities to fight pagans and infidels.

William came home from his southern adventures in 1391 or 1392. Having requested support from God himself in the Holy City (the original crusader target), he marched east once more. He spent the next two campaign seasons in Prussia, with the Teutonic Knights.

The death of his father in 1393 prompted William’s return. He now became Duke of Jülich as well. Although this enlarged his domains, William also got a few new and difficult neighbors - like Cologne, Cleves and Mark.

Hostilities between Brabant and Guelders also flared up again. And William even got into a bit of a conflict with the Holy Roman Emperor himself. Since he was now sporting the double ducal title “of Guelders and Jülich”, he became a bit too influential for the emperor’s liking.

But, despite all that, William found time for further crusades. We find him in the East once again in 1399, on campaign with his Teutonic friends. He probably made another Reise in 1400.

Local politics then required his presence at home as another conflict in the Empire’s west was building up. This time, Holland rather than Brabant would be the enemy. But, whilst preparing to invade the county, William fell ill.

He died on February 16, 1402.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Like a typical late medieval nobleman, William had made prestige his overarching goal. He spent lavish sums, often against the advice of his more prudent councilors, on the stature and grandeur of his court. He also maintained as many men-at-arms and knights as his treasury would allow, and then some.

With it, he undertook five Reisen to the Baltic. Although he spent one almost entirely in captivity, the other four were resounding successes - at least in the eyes of his allies, the Teutonic Knights. On top of that, William accrued two ducal titles, became a Knight of the Garter, and made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

William of Guelders thus became a role model for much of the Western European nobility. He demonstrated that, in an era when the Holy Land was long lost to the muslims, the crusader ideal was alive and kicking. The Teutonic Order provided unprecedented opportunities for glory in the Baltic and William grasped them with both hands.

His expenses nearly made him go personally bankrupt but did revitalize the economies of Guelders and Jülich. The influx of money also helped reconciliation with the nobles who had at first opposed his reign. As a testament to William’s power, none of these noblemen rebelled again after his death.

In the event, William’s brother succeeded him in a smooth power transition. A generation later, Guelders and Jülich parted ways again as William’s cousin and nephew divided his domains. This greatly weakened the position of Guelders during the 15th century, when the Burgundian dukes started to encroach on the Netherlands.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning - at no additional cost to you - we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Featured Image Credit: Rs-nourse (Wikimedia)

Comments are closed.

This website is my aspiration, perfect written content.

Thank you so much, Repke! I’m humbled.

Just a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw outstanding layout.

Much appreciated, Keeth! <3

This design is wicked! YWonderful job. I really loved what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

Thanks a lot for your awesome feedback, Janne! 😀

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Thank you,

Thanks so much, Margeret!

I have to thank you for the efforts you have put in penning this blog. I really hope to see the same high-grade blog posts from you later on as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own, personal blog now 😉

Wow, that’s amazing, Jimmie. Good luck!