MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

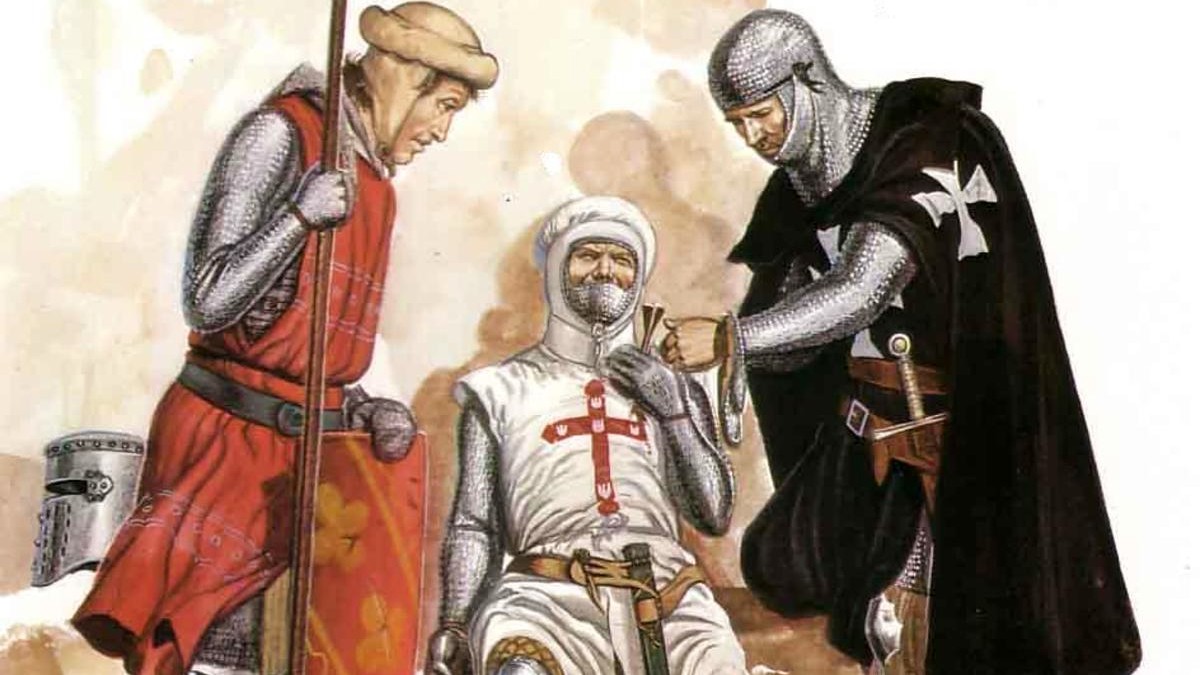

In an age before modern medicine, the medieval Order of the Knights Hospitaller performed the goriest of tasks. They performed surgery, took care of the sick, and even tried to cure lepers. Although a military order, the Hospitallers were sworn to tend to the injured and ill. They were the Knights of the Hospital, after all.

In this second piece on Hospitaller history, we’ll focus on the moral purpose of the Order in general and how Hospitaller healthcare worked in particular. This article is part of a larger series on the Knights Hospitaller that is largely historical but with a deliberately current perspective. Grab the other essays here:

The first episode covers the Order’s internal organization and structure, as well as its diplomatic relations.

The third episode covers the Order’s economic and technological agenda as well as its overall legacy.

After protecting the Holy Land from infidel incursions, curing the injured and caring for the ill was the most essential part of the Knights Hospitallers’ moral purpose. Indeed, it was the fundamental raison d’être of the Knights; they were officially called the “Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem”.

Even modern CEOs, like BlackRock’s Larry Fink, admit that “purpose is not the sole pursuit of profits but the animating force for achieving them” and that “it drives ethical behavior”. If a modern investment company can reason like that, one can imagine the heartfelt reasons most Hospitaller recruits would have entertained when joining the Order.

Because, as it stood, there were plenty of other options. The “competitor” brethren of the Knights Templar or the Teutonic Order provided employment, too. However, even in an environment so steeped in crusading spirit, the Knights Hospitaller stood out for having a strong and unique sense of purpose in relation to their medical mission. It defined them from the beginning.

According to the Rule, which was the foundational document of the Order, “the reason for the Order’s existence is the care of the sick and poor”. It went even further, stating that - in a legal medieval sense - the needy “owned” the Order. They were, so to speak, moral “shareholders” of the Knights Hospitaller.

Furthermore, the Rule commanded the Hospitaller to be engaged “solely in acts of mercy” and, interestingly from a financial perspective, to “raise cash for the Order’s mission”. Armaments, warfare and even fighting the infidel played second fiddle in the Hospitallers’ foundational charter. One could argue that the Knights Hospitaller were medics first, and soldiers second.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

An intriguing insight into how the Hospitaller hospitals operated was given to us by king Andrew of Hungary. He visited the Order’s infirmary in Acre, in the Holy Land, around 1217 CE. Later, he wrote down his impressions:

“[…] an innumerable multitude of the poor sustained every day with their daily sustenance, those sick and confined by weakness fed bounteously and with a plentiful variety of food, the bodies of the dead buried with due respect and…now engagement in constant warfare against the adversaries of God and the enemies of Christ’s cross.

— King Andrew of Hungary

Even though he was an outsider, this king clearly described the threefold mission of the Knights Hospitaller: the poor, the sick and the dead. At the time, these elements were rather evenly balanced. (The Order slowly shifted its emphasis to the fourth element, warfare, once it had established a sovereign state on the now-Greek island of Rhodes.)

The vocation of the early Hospitallers was to minister to the “holy poor” when they were sick and to bury them when they died. Gifts to the Order were - legally speaking - made “to the poor of Christ”, of whom the Hospitaller grandmaster was the “guardian”. All these expressions and formulations were of great value to the medieval Hospitaller Knights.

To give another example, each Hospitaller Knight abased himself by calling himself a “serf and slave” to his lords, by which he didn’t mean his superiors but - again - the sick. In an age rife with feudal rights and obligations, this meant that the Hospitallers fundamentally declared themselves to be unfree. Legally bound to the needy, the Order had but one superior: the disadvantaged - and, of course, their ultimate champion, God himself as well as his vicar on earth, the pope.

In practice, the above turned out to be a smart move. Feudal monarchs looked at the Order’s wealth and possessions with jealous eyes. Many medieval kings or emperors would have loved for the Hospitallers to swear feudal fealty to them.

But because they were “publicly owned” by the poor and sick, the Hospitaller Knights could claim that this was legally impossible. They already had a master. This play of words allowed them to escape many thorny legal disputes with the advocates of the reigning monarch nearby.

It also allowed the pope to hold on to the Order’s overall allegiance, even though this was often mostly nominal. Without the legal framework described above, an ambitious king or emperor would probably have tried to transfer the sovereignty over the Knights Hospitaller to himself. But surely, the Holy Father could now reason, no truly christian monarch would place his will above the needs of the infirm?

Another useful “exit” from the medieval power pyramid that the Hospitallers exploited, was that they took in both male and female patients. The Knights Hospitaller stated that their mission - and God’s love and care - was of paramount importance to humankind entire, surpassing “normal” laws. In the same vein, they unprecedently looked after non-christians as well; an exceptional stance for a crusading military order.

One could almost see a medieval precursor to the International Red Cross in the daily practices of the Knights Hospitaller and their legal ramifications. (An even more modern example of what the Order can inspire is the medical battalion named after it that’s currently active in Ukraine.)

As a result of their familiarity with medical matters, the Knights Hospitaller were singularly receptive to health threats. While reigning over the island of Rhodes, the Order managed the sanita, or public health, by taking preventive measures. After all, epidemics like cholera and plague were frequent during the Middle Ages.

When a huge earthquake devastated the nearby island of Kos in 1493, the Order promptly dispatched two galleys stocked with medical professionals and supplies. Additionally, the Order’s decision-makers authorized the creation of a passage from the coast to the island’s marshes in order to clean the environment and avoid probable diseases following the earthquake.

The Hospitallers’ most glaring public health emergency turned out to be the terrible epidemic of 1498, which killed thousands of Rhodians. The Grand Master immediately implemented a number of public health management steps:

These policies plainly weren’t all that different from how modern societies coped with COVID-19. Furthermore, the Order forbade gambling and prostitution, since it was thought that the demoralization of island life was a contributing factor to the disease.

Epidemics are one thing; however, the most daunting aspect of medieval healthcare was everyday hygiene. Catastrophes easily draw the most attention but, statistically speaking, it’s the silent killers that are the most lethal. The Knights Hospitaller dealt with the regular aspect of healthcare in interesting ways.

As an “international” organization, the Order could draw in medical professionals from all over Europe, and even from various religions. The most capable of doctors often ended up in the Hospitallers’ ranks, attracted by the Order’s overarching mission to humanity. In fact, this multi-ethnic and multi-religious recruitment practice even led to internal competition regarding which “nationality” could wield the most effective treatments. (Sometimes these discussions became unhealthy matters by themselves, leading to dying patients because some proud physician wanted to make a point.)

Exemplary in this case was the jew Jacuda Gratiano, fisicus et professor artis medicine (“physician and medical professor”). He was recruited into the Order on his merits; his religion apparently was no obstacle. His initiation procedure, then, was a manifestation of how the Knights Hospitaller mixed and matched all these various backgrounds: Gratiano was kindly asked to swear his oath to all the eight “nationalities” of the Order but was allowed to do so on jewish relics.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

As professional pioneers of (post-)battlefield medical treatments, the contributions of the Knights Hospitaller are widely appreciated. Their expertise developed further into early traumatology and surgery: the Order not only employed doctors and knights, but also monk-nurses and specialized surgeons (the medicus cyrurgicus).

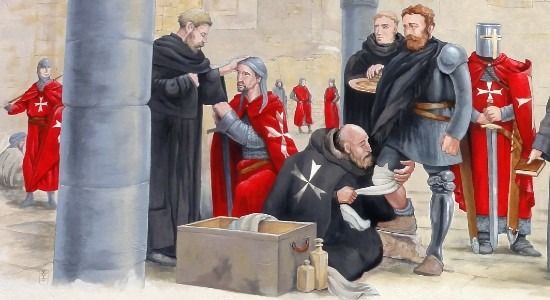

The greatest contribution of the Knights Hospitaller to modern medicine is the establishment of dedicated, professional hospitals. Prior to the Crusades, the state of European medicine was not that great. It was concentrated around monasteries, often more focused on care than cure.

Treatment options were limited and the cost of admission was high, to the point where healthcare was almost inaccessible to the common man.

Yet, as a crossroads of cultures, the Crusader States allowed for a flourishing of medical science. Knowledge of treatments and medication now began to flow more freely from the Arab world to the Crusaders. The open-minded recruitment policy of the Knights Hospitaller played a large part in this.

What’s more, evidence of an early ambulance service also exists, as field hospitals and transport were rare during this period. The Hospitallers had a system for transporting the sick, which again shows a quite advanced practice ahead of its time. In a way, you stand to experience a part of Hospitaller medical legacy every time you hear an ambulance’s siren.

The greatest achievement of the Knights Hospitaller was certainly their very bedrock, the Jerusalem hospitaler.

It quickly became a unique and advanced institution. Halfway through the 12th century, it could hold over 2000 patients, used a variety of medicines, had dietary regimes and hygiene practices, and was staffed by professional doctors, trained to both care and attempt to cure on a large scale - far in advance of most European hospitalia. It was a product of Western monastic care and Islamic medicine with the aim of organized healthcare.

The Hospitallers preserved this concept and their knowledge throughout the centuries and across geographies. Furthermore, they admitted all patients regardless of their origin, status, or sex, including muslims and jews, demonstrating an ethos of equal care that seems almost modern.

As a testimony to Hospitaller achievements, the Jerusalem infirmary itself served as the central cause and inspiration for medical change in the West. New institutions emulated its practices and style throughout Europe - thanks, in part, to the network of power and influence that the Hospitallers themselves had established across the continent. Their brothers in the Teutonic Order especially espoused the medical cause as well, constructing competent hospitals in their state - most based on Hospitaller examples.

In the next installment of this article series, we’ll study the finances and economic organization of the prosperous Knights Hospitaller. (coming soon)

- advertisement -

- article continues below -