MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

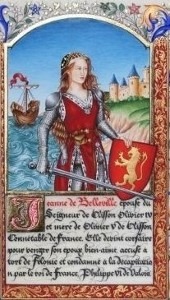

During the 1340s, a princess born on French soil plundered French shipping in the Channel and raided coastal villages in Normandy, France. The noble lady, called Jeanne de Clisson, usually killed the entire hapless crew or and town that was on the receiving end of her fury. Except for the last man, who she left alive to scurry back to the king of France with another horrifying story about her exploits. This ruthless strategy soon earned her a nickname at the French court: the Lioness of Brittany - since she was of Breton birth.

Jeanne had painted her ships black and her sails crimson. Death and blood were evidently her goals. She named her flagship My Revenge.

The question is, what led the Lioness to turn on her fellow countrymen in such a grisly manner?

Grab a short intro to the Kingdom of France from our Medieval Guidebook.

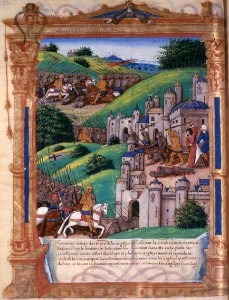

A few years earlier, war had broken out between the kings of France and England. The tension between the two monarchs had been brewing for a while. The French kept trying to gain control over English lands on the continent. Provocations had even gone as far as skirmishes against border towns. Furthermore, the king of France had allied himself with the Scottish - threatening the Kingdom of England from the north.

What finally set the stage for an all-out war was a succession crisis. The French king died in 1328 without leaving brothers or sons to succeed him. Nearest in line to the throne was Edward III, king of England. Given the already heated rivalry between France and England, the French nobility firmly rejected his claim. They installed their own candidate on the throne as king Philip VI.

At first, king Edward acquiesced in this decision. But the French continued their provocative policies. A large French fleet was sent to the Channel, seemingly preparing for war. Then, in 1336, France formally annexed Gascony, an area now in modern France but at the time one of medieval England’s most prized possessions. The following year, king Edward had no other option than to declare war on king Philip of France.

This move ignited a devastating and century-long conflict, filled with famines, epidemics and other hardships. On account of its length, this epoch-turning struggle became known as the Hundred Years’ War.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Brittany, in our day and age a region in western France but independent at the time, was swiftly sucked into this conflict. During previous centuries, the Duchy of Brittany had intermittently leaned towards both France and England - depending on whatever suited Breton interests the most at the moment. On this hazardous crossroads between two major medieval powers, we find the Lioness of Brittany.

She was born as Jeanne, somewhat to the south of Brittany. In 1330, she married Olivier de Clisson, a wealthy Breton nobleman. Jeanne and Olivier faced a difficult political choice eleven years later when Brittany was thrown into the cauldron of the Hundred Years’ War.

The reason for this turn of events was the duchy experiencing a succession crisis of its own. The duke of Brittany had died without issue as well. On his deathbed, when he was presented with the question of who should succeed him, he answered:

“For God’s sake, leave me alone and do not trouble my spirit with such things.”

— John III, duke of Brittany

Unsurprisingly, both France and England rapidly grew more interested than usual in Breton affairs. The French presented an official candidate, forcing his opponent to choose the English side in return. Thus, the crisis spun quickly out of control, and the War of the Breton Succession became an official proxy conflict of the Hundred Years’ War.

Jeanne and Olivier both possessed extensive lands in France. Siding with the English would immediately lead to the seizure of their estates outside Brittany. Therefore, the De Clissons saw no alternative than firmly choosing the French side.

Meanwhile, the English army marched on Vannes, Brittany, and promptly besieged the city. King Edward described Vannes as “the best city in Brittany after (…) Nantes”. The French king sent Olivier de Clisson to Vannes to assist with the city’s defense.

During one of the sorties, Olivier was captured by the English. While being held prisoner, the pope mediated to prevent the conflict from escalating even further. King Edward of England and king Philip of France obediently agreed to a truce and prisoners were exchanged.

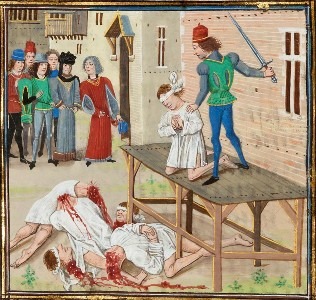

The English, however, demanded such a low ransom for Olivier de Clisson that the French king grew suspicious. Surely - he reasoned - if Olivier had presented a bigger problem for the English army, king Edward would have demanded a higher sum in return for his release.

Convinced that Olivier had taken up the defense of Vannes too lightly, king Philip had him arrested, tried and executed. He sent Olivier’s head to Nantes, Brittany, to be put on a lance at the gate as a warning to other “traitors”.

Jeanne was enraged by the execution of her husband, which she regarded as cowardly murder. Upon hearing the news, she traveled to Nantes with her two young sons. She showed them the decapitated head of their father.

Jeanne swore revenge. Pre-empting the seizure of her lands by king Philip, Jeanne sold all her possessions. With the money, she hired loyal men and launched a guerilla insurgency.

Her band of rebels attacked numerous castles throughout Brittany with great success. One garrison she took entirely by surprise. Her soldiers killed everybody except the last man and sent the frightened survivor back to the French ranks to spread tales of terror.

Thus the legend of the Lioness was born.

King Edward immediately took a great interest in her campaign for revenge. He supplied Jeanne de Clisson with three warships to harass the French in and near the Channel. The Lioness had turned privateer.

In the waters between France and England, Jeanne seemingly found her true calling. She sunk many French ships and assaulted a great number of coastal villages in Normandy. Her pirate career lasted for thirteen long, blood-soaked years.

Eventually, the French navy managed to sink Jeanne’s flagship, aptly named My Revenge. The Lioness got away with her two sons but instantly went adrift. Lost on the high seas without food and water, her son Guillaume died of exhaustion in her arms.

After five days, Jeanne was found and rescued by English sympathizers.

That same year, a battle took place that decided the fate of Brittany. Sir Walter Bentley scored a victory over a French army twice the size of his forces. His longbowmen inflicted mass carnage on the French cavalry forces.

More importantly, the French candidate for Brittany’s ducal title was captured by the English. This greatly increased English control over Breton affairs. Much contented with this state of affairs, the English king richly compensated Sir Bentley with numerous Breton lands and castles.

As it happened, both Bentley and the Lioness were in Brittany at the same time - and single. Walter and Jeanne were by now key players in the conflict and nothing short of heroes in the English camp. They got married straight away.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

Jeanne settled in one of the castles that king Edward had given to Walter Bentley: Hennebont. There, on the Breton coast, she died three years after marrying Bentley. One can only hope she found some semblance of solace there.

The Lioness of Brittany had taught the king of France that he couldn’t summarily execute his noblemen without suffering the consequences. In true pirate fashion, she vengefully inflicted a massive amount of damage to the French war effort and lived to tell the tale. Jeanne de Clisson became a name not soon forgotten at the royal court in Paris.

The War of the Breton Succession was finally settled six years after Jeanne’s death. Alas, the Hundred Years’ War continued for another 88 years after that. One of the Lioness’ sons played a major role in the conflict as well, which we’ll cover in a later report.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning - at no additional cost to you - we will earn a small compensation if you click through.