MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

The Hundred Years’ War was a series of drawn-out conflicts in Western Europe. Taken together, these confrontations actually covered over 116 years. The central question was about the right to rule medieval France. The English and French kings disputed the other’s claim to the throne, leading to war. The rivalry ended up causing over a century of conflict, ruin and deprivation.

This is a short intro from our Medieval Guidebook. Dive deeper into the subject by reading our articles about it.

In 1328 CE, king Charles IV of France died without leaving sons or brothers to succeed him. Technically, the closest male relative alive was his brother-in-law, the English king Edward III. However, the French nobility dreaded the thought of an Englishman on the throne of France. So they put forward the late king’s cousin as their counter-candidate. After the English grudgingly agreed to this, he was crowned as king Philip VI of France.

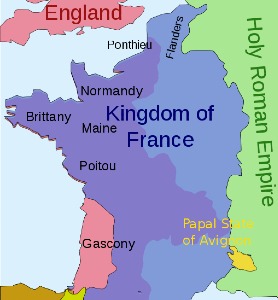

Despite this temporary triumph of diplomacy, it was under king Philip’s reign that the Hundred Years’ War broke out. At the time, tension between the French and the English royal courts had been brewing for ages. During the High Middle Ages, the Angevin Empire of the English kings had dwarfed the French royal domains. But over the course of the centuries, the kings of France had chipped away at the English lands on the continent. The new king Philip ruthlessly continued this strategy, leading to open warfare.

The last straw was France’s outright annexation of Gascony, the only major English holding left in continental Europe. King Edward responded in 1337 with a declaration of war. He also reiterated his claims to the French throne. This laid the groundwork for a much larger conflict than a ‘simple’ war over Gascony. Thus the Hundred Years’ War began, far outlasting both Philip’s and Edwards’ reigns.

The Hundred Years’ War mainly took place on French soil. An important reason for this was the Battle of Sluys, quite early in the war. During this confrontation, the English destroyed the better part of the French fleet. Afterward, they could dominate the Channel and prevent French invasions. Meanwhile, Edward’s son, nicknamed the Black Prince for obscure reasons, scored similar successes on land.

A major battle was fought by the Black Prince at Crécy in 1346. English longbowmen dealt massive damage to the French cavalry-based army and were victorious. In 1356, the Black Prince outdid himself by winning again at Poitiers. One of his cavalry units hid in a forest nearby until the French routed, cut off their retreat, and captured the king of France himself.

Evidently, the English did very well at first. A succession dispute in Brittany ended in the region going over to England as well. Consequently, king Edward pressed for an advantageous truce. Because the Black Death was simultaneously ravaging France more than England, the French yielded. The First Peace was signed in 1360.

It was called the “first”, because the war flared up again only nine years later.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

From 1369 to 1389, France made somewhat of a comeback. The French army now avoided large-scale battles with the English. Instead, they increasingly relied on guerilla warfare. The English responded with likewise cruelty, as the conflict descended into total war. By intervening in a Castilian civil war, the French also made new, Spanish allies.

Their newfound friends set the English fleet aflame at La Rochelle, isolating the English forces in France. To make matters worse, king Edward III finally died in 1377, leaving his 10-year old grandson on the throne. (The Black Prince had died one year earlier.) The Kingdom of France didn’t fare much better, as Charles VI became its new king in 1380 at the age of 11. With two infant monarchs at the helm and widespread destruction, plague and economic crises plaguing the warring parties, both sides agreed to a truce.

A “Second Peace” was concluded in 1389. It lasted until 1415.

In 1392, the French king Charles VI suddenly became mad. The question of who should rule as regent sparked internal disagreements. Both the king’s uncle (the Burgundian duke Philip) and his brother Louis vied for this position. The rivalry between Philip’s “Burgundian” and Louis’ “Armagnac” party led to an all-out civil war. In 1415, the English intervened and reignited the Hundred Years’ War.

King Henry V of England immediately achieved a great victory at Agincourt, where he killed over 40% of the French nobility. Afterward, he retook Normandy and the Burgundians captured Paris. Charles VI of France was forced to declare his son, the French crown prince, illegitimate. He also agreed to marry his daughter to Henry V, so their descendants would finally and formally rule France. The English victory seemed complete.

At this moment, one of France’s darkest hours, country girl Jeanne d’Arc revived French spirits and morale. She lifted the English siege of Orléans and had the French crown prince ceremonially crowned as king Charles VII at Rheims. Although Jeanne was captured and burnt at the stake by the English at age of 19, she had turned the tide. In 1435, the Burgundians went over to the French side. With the help of top-notch artillery and a professional standing army, the King of France then proceeded to push the English back.

In 1453, the final battle took place at Castillon, which ended in a French victory. Hostilities ceased after that, as France was all but exhausted and England descended into civil war - partly because of the course of events in the by now unpopular Hundred Years’ War. Formally, the French and English kings remained at war for 22 more years. In 1475, a peace treaty was finally agreed upon by both, 138 years after the start of the war. On account of its length and complexity, the conflict became known as the Hundred Years’ War.

It had changed Western Europe forever. The English only held on to Calais, but continued to claim the title “King of France” until 1803. The French, on the other hand, had been on the brink of destruction multiple times, but after many defeats and extensive epidemics, famines, recessions, catastrophes, and other hardships ultimately came out the “victor” of this ruinous, calamitous and almost apocalyptic conflict.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Grab a short intro on another conflict from our Medieval Guidebook.