MedievalReporter.com

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Join our newsletter!

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

Covering history's most marvelous millennium

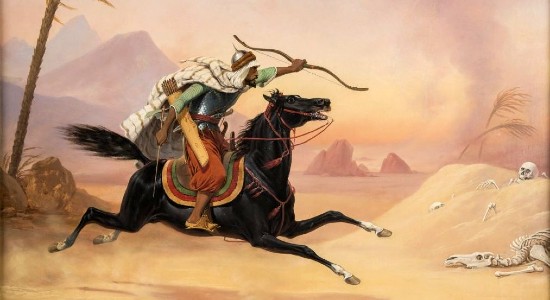

The Cumans lived in an area stretching from Romania, Hungary and Moldavia in Eastern Europe to Mongolia in Inner Asia. This was a steppe area, flat and devoid of major mountain ranges. Horses were therefore central to the Cuman culture.

Over time, the Cumans fused with the famous Turkic tribe of the Qipchaqs. The confederation that they created thus had many Asian-looking inhabitants, but the Cumans themselves were famed for being blond, blue-eyed and fair-skinned.

The Mongols eventually scattered them to the wind. Many Cumans fled into Eastern Europe and settled there, whilst others seized power in Egypt.

Evidently, as with most nomadic peoples, the Cuman story was a tale of travels.

This is a short intro from our Medieval Guidebook. Dive deeper into the subject by reading our articles about it.

The Cumans-Qipchaqs enjoyed a nomadic lifestyle, moving their herds from one pasture to another - wherever the grass was greenest. They thus moved all the way up and down the Great Eurasian Steppe from the 10th to the 13th century CE. Therefore, the frontiers of their confederation were not as solid as modern, national borders. The Cuman-Qipchaq state was not territorial; rather, wherever they roamed, that’s where their state was. The lack of political unification by a strong central power was exactly why they could “occupy” such vast lands: the realm consisted of loosely connected tribal units that represented a dominant military force, led by khans who acted on their own initiative.

Cumania was, in fact, a loose term, used by Western European, Rus’, Byzantine, Islamic, and Chinese chroniclers - all from sedentary civilizations - who never even traversed the area. In practice, Cumania comprehended the Black Sea’s northern shores and anything north of the Jaxartes. Its northern “border” was the dense forestland of present-day Belarus and Russia, which didn’t lend themselves to a pastoralist lifestyle. To the south and west, the Cumans-Qipchaqs ranged as far as Persia, Hungary and the Caucasus Mountains. Consequently, Cuman commercial interests stretched from Central Asia through Crimean harbors to markets as far away as Venice.

The Arab emissary Ahmad ibn Fadlan, who actually traveled to the region, already mentioned the Qipchaqs in the 9th century CE. A few centuries later, Italian merchant Marco Polo equated Cumania with the Pontic-Caspian steppe. But a Berber scholar probably best described the Cuman lands:

“This wilderness is green and grassy with no trees, nor hills, high or low.”

—Ibn Battuta, 14th-century Moroccan scholar

The Cumans conquered, merged, and/or allied with the Turkic Qipchaqs - the details of how this confederation came to be remain elusive. The Qipchaqs (or Kipchaks) were the early inhabitants of eastern Cumania, from the 6th to the 8th century CE. They frequently fought with other Turks - such as the Khazars - and the Persian and Chinese empires. Their martial prowess eventually allowed them to dominate the Kimek Khaganate, which had grown in northern Kazakhstan. The flexibility and fluidity of steppe politics subsequently caused them to mix and mingle with the Cumans.

Whereas the Qipchaq inhabitants of the Cuman confederation would have looked rather Inner Asian on account of their Turkic heritage, the Cumans were different. Cuman people were reported to have mostly blond hair, pale skin and blue eyes. In Slavic languages, they are called Polovtsians, or Polovtsy - meaning “blond”. Germanic speakers called them Folban, Vallani, or Valwe - all meaning “pale”, compare “fallow” in English. And Armenians referred to the Cumans as “the Blond Ones”.

Both their physical appearance and the martial prowess stemming from their harsh life on the steppe made Cuman people attractive in the eyes of their contemporaries. As neat as that might sound, this was not always a bonus in the medieval world: Cuman women were often abducted as brides-to-be, and men were enslaved to serve as soldiers (mamluks) in armies as far away as Egypt. The Cumans participated in this behavior just as passionately, though. With the Qipchaqs, they spent many centuries doing what most steppe horsemen do: raiding, pillaging, marauding - essentially racketeering - agrarian settlements.

They even took equipment like mangonels and ballistas with them to besiege walled cities - a practice that was soon copied by other Asian riders who spelled the end of Cumania.

- advertisement -

- article continues below -

As the Mongols stormed west in the 1220s, they targeted Persia first. But as the Persian shah fled across the Caucasus, the Mongols chased him in great number and thus came into conflict with the Cumans. By then, the Cuman-Qipchaq khans had come to an understanding with the Rus’ principalities in the area. Whereas the Cumans had initially fought them over and over again, they now served as cavalry archer mercenaries to many of the Rus’ princes. Now, confronted with the Mongol onslaught, Cumans and Rus’ cooperated and marched east with a force allegedly numbering over 80,000.

Somewhere in modern-day eastern Ukraine, the two armies met. The Mongols showed the Cumans-Qipchaqs who were the better steppe horsemen and killed over half of the allied force - a staggering number. The Cuman confederation imploded straight after. Most of the survivors fled west, into Europe, where they violently forced themselves upon Hungary, Bulgaria and the Balkans. A Byzantine statesman complained that they turned the whole area into a desert.

The Cumans were such a threat to Hungary that the Magyar king invited the Teutonic Knights to watch his eastern border. However, the Teutonic Order grew so powerful in such a short term that, within years, the Hungarians expelled them again. Still on the run for the Mongols, the Cumans quickly resumed migrating towards Hungary. But neither there, nor in Bulgaria, were they safe: the Mongol armies ravaged both countries, killing or enslaving a lot of Cuman refugees. However, after the Mongol threat withdrew around 1250 CE, many Cumans assimilated into a resurgent Magyar society - one woman, Elizabeth ‘the Cuman’, even became Queen of Hungary.

Other Cumans retreated east against their will and were forcibly recruited into the Golden Horde, one of the successor khanates of the Mongol Empire.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning – at no additional cost to you – we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

Grab a short intro on another civilization from our Medieval Guidebook.