MedievalReporter.com

Master the Middle Ages in mere minutes

Join our newsletter!

The latest on history's most marvelous millennium

The latest on history's most marvelous millennium

Born on the Russian steppe, the fair-skinned and probably blue-eyed Baibars became Sultan of Egypt before he was 40 years old. A tall and menacing commander, he dared to confront the Mongol hordes in open combat. Other campaigns of his design paved the way for the complete ejection of the Crusaders from the Middle East.

Baibars was enslaved at age 19. Working his way up from the lowest rung of society, he chose the career path of a mamluk - a slave-soldier. His military successes allowed him to build up so much authority that he founded Egypt’s first truly mamluk dynasty.

How does one go from slave to sultan within 20 years?

Grab a short intro to the Qipchaqs (Baibars’s tribe) from our Medieval Guidebook.

Baibars was born in the Sea of Grass, the Great Eurasian Steppe that stretches from Korea to Hungary. Neither his date of birth nor his exact origin is known for sure. But he came into this world either in 1223 or 1228 CE, and he hailed from either southern Russia - between the Volga and Ural rivers - or northern Kazakhstan.

Life on the steppe had always been rough but the early 13th century was an especially dangerous time to grow up in this area. Genghis Khan was storming west during this period, his Mongol army subjugating almost anything they found on their path. Baibars belonged to the tribe of the Qipchaq Turks and the Mongols sought to destroy their state, too.

Baibars’s parents, having heard the stories about Genghis Khan’s sanguine exploits, decided not to wait out the storm and fled. They took a ship across the Black Sea, possibly from Crimea, and sought refuge in Bulgaria. The Bulgarians, always in search of steppe warriors to threaten the northern Byzantine borders with, allowed Baibars’s parents to settle.

At the time, the fledging Bulgarian realm seemed like a safe place to build a new life. But the menacing Mongol hordes pressed on and invaded the Balkans as well in 1242. Bulgaria fell prey to widespread devastation as the invaders destroyed as much as they could.

Refugee Qipchaqs were especially hunted down. Baibars witnessed his parents being massacred by the Mongols, right in front of his eyes. He himself was taken captive and taken away as a slave.

His fate looked exceedingly grim.

Befitting of the commodity he now was, Baibars changed hands a couple of times. He was sold by the Mongols at a slave market in the Sultanate of Rum, in modern Turkey. His buyer was a middleman who sold him for a higher price in Syria to a high-ranking Egyptian official.

This dignitary brought Baibars to Cairo, the capital of the mighty Ayyubid Sultanate. It controlled most of Egypt and Syria at the time and was called “Ayyubid” because of the family name of its celebrated founder, Saladin Ayyub.

- advertisement -

[show_ad_here]

- article continues below -

Soon after Baibars arrived in Cairo, his master got into an argument with the reigning sultan, who was Saladin’s great-nephew. The discussion swiftly led to the confiscation of all the officer’s goods, including his slaves. Baibars was now the sultan’s private property.

Dreary economics aside, this propelled Baibars straight into the household of what was probably the most powerful man of the Middle East - that is, on paper. As it happened, the Ayyubid sultans had grown increasingly dependent on a caste of slave-soldiers, called mamluks. And they specifically recruited Turkic men from Central Asia for this, because Turks were famous for their ferocious battle prowess.

Baibars, being a Qipchaq Turk, fit the job description perfectly. A man of great physical stature, he not only made for a good soldier but was also cut out to be an authoritative leader. With many enemies descending upon the Ayyubid Sultanate, Baibars soon got to show what he was made of.

Crusaders were the main opponents of Egypt at the time. Although Saladin - the sultan’s great-uncle - had liberated the holy city of Jerusalem from christian occupation, there were still Crusader states in the Levant. On top of that, new crusades kept arriving in the Middle East, trying to shift the balance of power.

In that vein, the Holy Roman Emperor himself had come to the Holy Land when Baibars was little. The emperor negotiated with the Ayyubid sultan and reinstated christian control over Jerusalem. It was short-lived, though: while Baibars became a mamluk, the Ayyubids reconquered the city.

It led to renewed calls in Europe for the liberation of the holy sites, prompting the Seventh Crusade. This time, the French king Louis IX “took the cross” and embarked on a military campaign to the Levant. He stopped on the island of Cyprus and set in motion the ingenious geopolitical idea he had devised.

As the Mongols were barreling down on the Middle East as well, Louis thought they would make for the perfect ally in defeating the Ayyubids. He sent an envoy from Cyprus to the Mongol khan. The Mongols responded cordially to the request but made demands as well.

The French diplomats were told the khan didn’t have allies, only vassals. So, in order for them to cooperate, both king Louis and the pope would have to submit to the khan’s authority. Louis’s idea turned out to be clearly naive and nothing came of it.

Wasting no more time, the French army went aboard again and sailed to Egypt to strike at the heart of the Ayyubid Sultanate anyway.

The French offensive had great success at first. The sultan was away, campaigning in Syria, and had left only a mamluk garrison behind in Egypt - enough to control the local population but insufficient to withstand the fearsome French fleet, allegedly numbering over 1,800 ships and boats.

Like a lightning strike, Louis IX occupied the coastal city of Damietta. Trying to shore up their position, the mamluks reinforced their defenses around al-Mansurah - a few kilometers inland. They were in full control of the defense of the sultanate’s heartland, begging the question what they needed the sultan for.

When their master finally did arrive, he fell ill and died. To make matters worse, he’d been in such a hurry to get back to Egypt that he had left his son and heir in Syria. A delegation was sent out to fetch him, but that took another couple of weeks.

His mother, the late sultan’s wife, was present in the army camp at al-Mansurah and tried to keep her husband’s death a secret. But, of course, word got out to the French and, emboldened by what they saw as God himself striking down their foe, the Crusaders moved to attack. Once again, the mamluks were in charge of defending Egypt - without their master present, they led the way.

The mamluk commander heard about the French advance while he was taking a bath. He hurried out, jumped onto his horse, and rode out to the battle raging outside the city, only to be cut down by the Knights Templar - who had also joined the expedition. Command now fell upon a blonde, blue-eyed Qipchaq Turk: Baibars.

Whilst the French scored a crucial tactical victory over the mamluks outside al-Mansurah, they still had to take the city itself. The French king wanted to reorganize his position and ordered his army to stay put. But his brother and the Templars wanted to defeat the Egyptians before the new sultan arrived at the scene.

Meanwhile, Baibars had come up with a cunning plan to turn the tide. He lured Louis’s brother and the Templars into al-Mansurah by simply opening the city gates. Thinking that the Egyptians were surrendering, the Crusaders rushed into the city - elated at their seemingly easy success.

As the gates were shut behind them, strategically placed mamluks attacked the French cavalry from rooftops and alleyways. The spaces were too narrow to fight in formation and the Crusader horses were unable to turn. The result was a massacre: Baibars’s soldiers killed the French king’s brother and 285 out of 290 Templar knights.

King Louis tried to negotiate a truce, but the new sultan arrived two weeks later. Determined to shore up support for his reign, he attacked the French main force immediately. Pestilence and hunger had thinned the Crusader ranks by then, causing a crushing defeat at the hands of the Ayyubid army.

Louis himself was taken prisoner, sending shock waves through the courts of Western Europe. With the Seventh Crusade utterly annihilated, Egypt was saved and the young sultan’s position seemed safe and secure. However, Baibars made sure he would not rule for long.

- advertisement -

[show_ad_here]

- article continues below -

The new sultan was called Turanshah. He quickly managed to alienate the clan of mamluks that Baibars belonged to: the Bahris. Rather than rewarding Bahri mamluks for their sacrifices in the war against the Crusaders, he elevated others - who had done little fighting - to high positions such as Master of the Sultan’s Guard.

Feeling their hold on power slipping, the Bahri clan decided to move preemptively. Turanshah gave a great banquet to celebrate his victory over and capture of the French king. After a deluge of food and drink, Baibars and a few of his mamluks rushed in and attacked their sultan.

In the confusion, they only managed to cut his hand as the sultan escaped the scene and fled into a tower next to the Nile river. Baibars then had his mamluks set the tower on fire. The flames forced Turanshah down, but he managed to escape the tower as well and dove into the river.

Supposedly, he was struck by a spear and several arrows whilst in the water. Still alive, he begged the mamluks to spare his life and even offered to abdicate. Baibars, though, had had enough of the spectacle, waded into the water, and hacked Turanshah to death.

A complicated chess game ensued regarding the sultan’s succession. His mother ruled for 80 days, before marrying a mamluk called Aybak, making him sultan. However, despite their military successes, the mamluks still didn’t feel secure enough to rule Egypt themselves.

So, after only 5 days of official rule, Aybak put a 6-year-old Ayyubid prince on the throne and retired to the position of atabeg - a Turkic title of high nobility. Nobody was fooled, though: Aybak and the mamluks fully controlled the infant puppet sultan.

Baibars spent the next few years campaigning in Syria, fighting Aybak’s wars. Ayyubid family members who were in control of emirates like Aleppo or Damascus refused to acknowledge Aybak’s de facto reign in Egypt. Baibars defeated most of them and brought Palestine and the Syrian coast back under Cairo’s rule.

His position strengthened, Aybak now felt confident enough to claim the sultanate for himself. He sidelined the young prince, sent him to his aunt, and made himself sultan for the second time - the first time being his brief 5-day stint. The caste of slave-soldiers had officially deposed Saladin’s bloodline in Egypt.

But, if one mamluk could just claim the throne without needing Ayyubid legitimacy, so could other mamluks. Aybak immediately began viewing his fellow Turks as a threat to his rule. He summoned a lot of prominent Bahri clan members to the palace at once.

As Baibars was making his way to the compound, he received a message that was not to be misunderstood. A decapitated head was flung from the courtyard and landed in front of Baibars’s horse. It had belonged to a close friend of his.

Baibars immediately understood what was happening: Aybak was running a full crackdown on the Bahris to eliminate rival claimants to the sultanate. Baibars turned his horse around, galloped out of the city, and fled into Syria.

- advertisement -

[show_ad_here]

- article continues below -

With his close associates, Baibars tried to damage Aybak’s interests in Syria while the sultan’s forces attempted to hunt him down. This went on for a few years. Aybak was eventually succeeded by sultan Qutuz, but he was just as hostile to Baibars.

Just when it seemed like Baibars would never be able to safely return to Cairo, a gigantic threat to Egypt’s survival arose. A new Mongol khan had taken over Genghis’s empire. And he was much more interested in conquering Southwest Asia than his predecessors.

He assembled a humongous host, possibly the largest Mongol army ever. It traveled west under command of the khan’s brother, Hulagu. With this campaign, the Mongols sought:

Hulagu departed from Mongolia in 1253 and accomplished the first four of these five objectives before 1260, killing both the Abbasid caliph and the last Ayyubid prince - eliminating Saladin’s bloodline altogether. The Mongols kept advancing at breakneck speed, capturing Aleppo in January 1260, and Damascus on March 1st. Only Mamluk Egypt still stood in the way of Hulagu’s complete domination of the Middle East.

Overly confident, the Mongol khan sent an intimidating dispatch to sultan Qutuz to force a surrender:

“From the King of Kings of the East and West, the Great Khan. To Qutuz the Mamluk, who fled to escape our swords.

— Khan Möngke’s missive to the mamluk sultan of Egypt, Qutuz

You should think of what happened to other countries and submit to us. You have heard how we have conquered a vast empire and have purified the earth of the disorders that tainted it. We have conquered vast areas, massacring all the people.

You cannot escape from the terror of our armies. Where can you flee? What road will you use to escape us? Our horses are swift, our arrows sharp, our swords like thunderbolts, our hearts as hard as the mountains, our soldiers as numerous as the sand. Fortresses will not detain us, nor armies stop us. Your prayers to God will not avail against us. We are not moved by tears nor touched by lamentations. Only those who beg our protection will be safe.

Hasten your reply before the fire of war is kindled. Resist and you will suffer the most terrible catastrophes. We will shatter your mosques and reveal the weakness of your God and then will kill your children and your old men together. At present you are the only enemy against whom we have to march.”

Qutuz responded in a brutal manner. He had the emissaries sliced in half and put their heads on spikes atop Cairo’s gates. The sultan knew the Mongols would be furious, but he also knew that Hulagu had retreated to the Caucasus to spare his horses the Middle Eastern summer heat. The Mongols had left only a part of their army - still numbering 20,000 - in Syria. Qutuz assembled his men and rode out to meet them.

Confronted with such a threat, the sultan couldn’t allow Baibars to raid his rear. So he reached out to his rival and offered him the governorship of Aleppo, should the mamluks win. With the Mongols as a common enemy and still looking for revenge for the massacre of his parents, Baibars decided to accept this olive branch and joined Qutuz’s forces.

The two armies met near Ain Jalut, in modern-day Israel. Because they were Qipchaq Turks from Central Asia, the mamluks were able to respond in kind to the cavalry-based steppe tactics that the Mongols employed. On top of that, Baibars and Qutuz were a surprisingly good team.

Baibars kept hitting the Mongol squadrons with hit-and-run maneuvers throughout the day, trying to provoke them into pursuit. Qutuz lay in ambush in the surrounding hills with the lion’s share of the Egyptian army. When the Mongols finally reached the highlands, mamluk warriors poured down and caught the enemy in a withering crossfire.

The Egyptians suffered heavy losses as well but managed to kill or capture almost all Mongols by the end of the day. Their commander was brought before Qutuz and said:

“Be not deceived by this event for one moment, for when the news of my death reaches Hulagu Khan, the ocean of his wrath will boil over, and from Azerbaijan to the gates of Egypt will quake with the hooves of Mongol horses.”

— The Mongol commander addressing sultan Qutuz after the Battle of Ain Jalut

The sultan was utterly unimpressed and beheaded the general.

- advertisement -

[show_ad_here]

- article continues below -

The battle was a severe blow to the confidence of the Mongol hordes, who had seldom experienced such a stinging defeat. The mamluks, on the other hand, felt invincible. Qutuz, in particular, imagined himself unassailable and, swollen with pride, refused to give Baibars the emirate of Aleppo as he had promised.

Their rivalry reinvigorated, Baibars decided he would not flee into the Syrian countryside again. It had not brought him much last time around. He accepted Qutuz’s decision for now and traveled back to Cairo with him.

However, fearful of another crackdown, Baibars was fully intent on killing the sultan before he was killed himself. Halfway through the journey, Qutuz ordered a short pause to hunt the surrounding area. Baibars joined him and, whilst Qutuz was chasing a hare, killed his sultan.

The senior commanders of the army met and proclaimed Baibars as the next sultan. In the Turkic tradition of the steppe, it was common for new rulers to simply take their title by killing their predecessors. This was understood as proof of the physical aptitude that made them fit to rule.

With the support of the mamluks, Baibars rushed to Cairo and entered the citadel to ascend the throne. He had murdered two sultans and fought a great many battles to get there. Less than twenty years ago, he had been a slave; now, he was Sultan of Egypt.

Baibars’s reign was the concluding act in a complicated power transition from the Ayyubids to the mamluks. Egypt saw five new rulers in the span of eleven years: Turanshah (1249-50, murdered by Baibars), Aybak (1250-57), his son (1257-59), Qutuz (1259-1260, murdered by Baibars), and Baibars himself. He brought back stability to the sultanate, though, and reigned until his death in 1277.

The mamluks would rule Egypt for the rest of the Middle Ages. Baibars’s rule turned out to be the beginning of an age of Egyptian dominance over the Eastern Mediterranean. From Cairo, the mamluk sultans oversaw the destruction of most of their enemies.

Before the century was out, Baibars’s descendants had kicked the Crusaders out of the Levant for good. Even the fight with the Mongols led to mamluk victories most of the time. (As Hulagu’s general had warned Qutuz before he lost his head, the Mongol revenge campaign did indeed come - but not until Baibars was dead.)

On top of that, by killing the last caliph and sacking Baghdad, the Mongols had greatly strengthened the prestige of Cairo. Who else was going to protect Islam from the Mongol menace? Hulagu’s expedition allowed Baibars and his dynasty to present themselves as the champions of the muslim faith, enormously enhancing the mamluks’ authority.

As sultan, Baibars showed he could do more than just warfare. He embellished Cairo with mosques, canals and beautiful bridges. He was a patron of science and medical research, established a four-day mounted message relay system to Damascus, and even built a cat garden.

Despite his murderous intent, it’s easy to see why this man is considered a hero in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and Kazakhstan.

Disclosure: we work hard to provide you with exclusive medieval reports and guides. To make the Middle Ages accessible to everybody, we’d like this information to remain FREE. Therefore, some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning - at no additional cost to you - we will earn a small compensation if you click through.

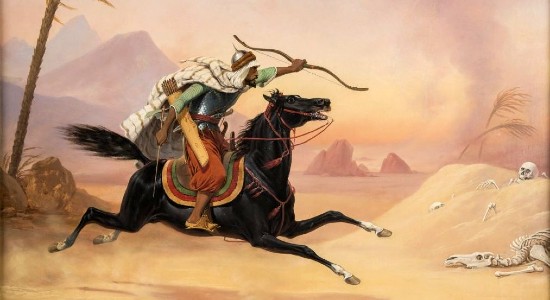

Featured Image Credit: Jangelles (deviantART)

Hey there! I’ve been reading your web site for a while now and finally got the courage to go ahead and give you a shout out from Atascocita Tx!

Just wanted to tell you keep up the great job!

Thank you so much for letting us know, Uta. It means a lot!

Hello, I like your website very much, I hope more people discover your website. Can you recommend a book about Sultan Baybars I ?

Thanks a lot, Onur! I think the three books we mention at the end of the article are the best ones to get started with the topic. With regards to Baibars specifically, I think “Mongols & Mamluks” is the best introduction - at least as far as his military exploits are concerned.

Here’s the link for your perusal. Happy reading!

You choose peace or war?

Hi! I think Baibars pragmatically preferred whatever suited him best at the moment. 😉

Hi Man,How Are You Doing

Great! Thanks for stopping by.